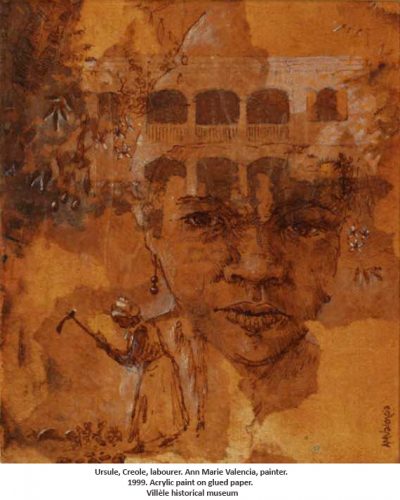

An article written by Reine-Claude Grondin, Historian

The official recognition of slavery in Reunion in 1983, 135 years after its abolition, gave credit to the idea that the silence surrounding this chapter of our past was the fruit of a deliberate policy of collective amnesia, orchestrated by the former landowners and their descendants.

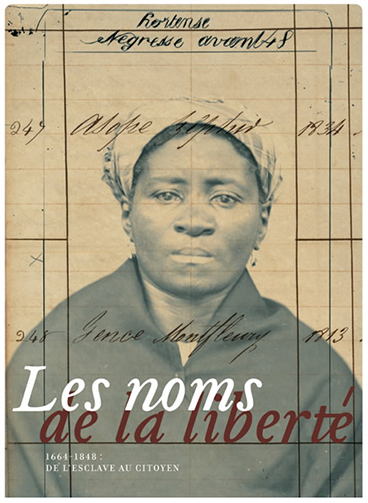

Indeed, the history of slavery, written exclusively by these actors, disseminated a watered-down version of slavery that created for the literate public the myth of a model colony, rendering invisible the violence of the system of slavery. The narrative of this history, exploited for the purposes of French colonial expansion, was paramount among the restricted number of readers up to the mid twentieth century. In the absence of any elite originating in the emancipated slaves following 1848, there was no alternative narrative to that of the aristocratic memory.

However, the absence of official recognition did not prevent the survival of private and family memories, dynamic and heterogeneous like a patchwork quilt. The mobilisation of this memory following the third generation of descendants of emancipated slaves created, in the present period, a past that had been deprived of a narrative up to the 1970s-1980s.

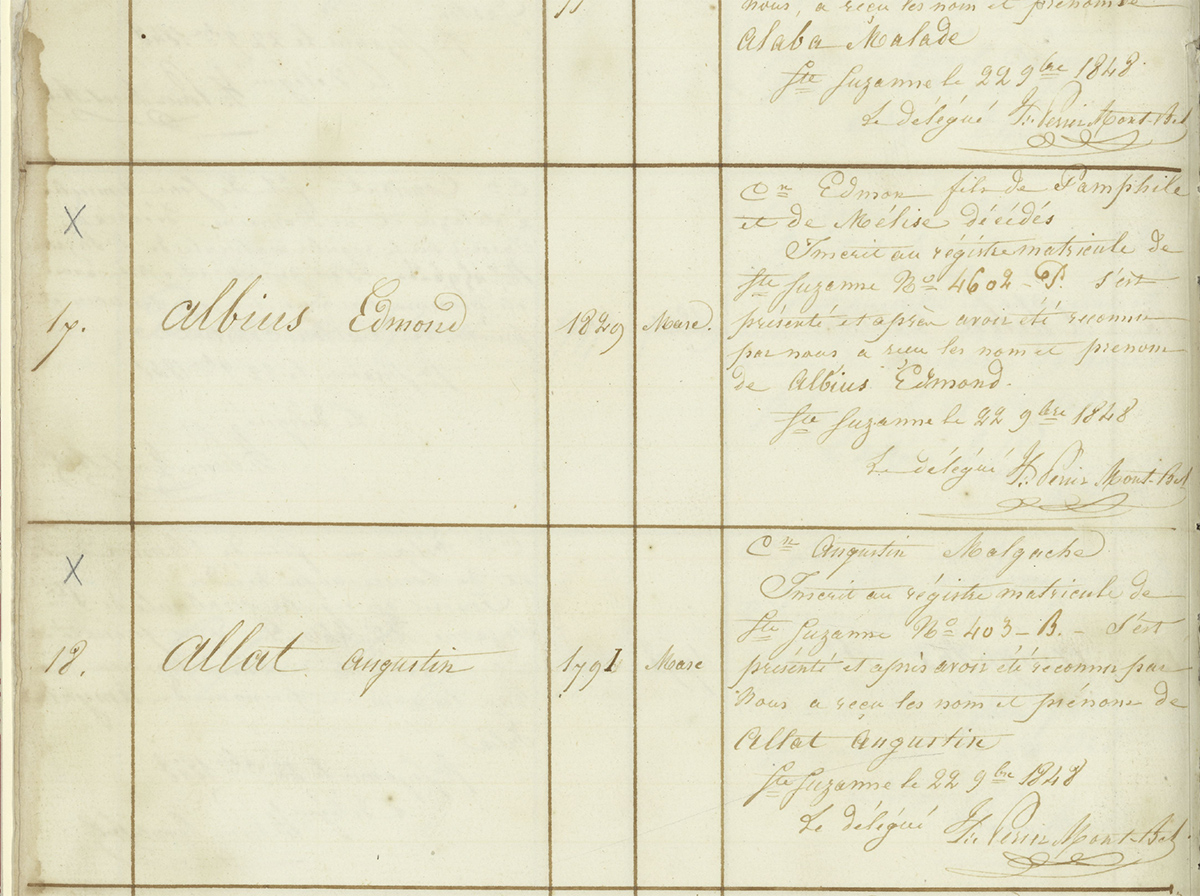

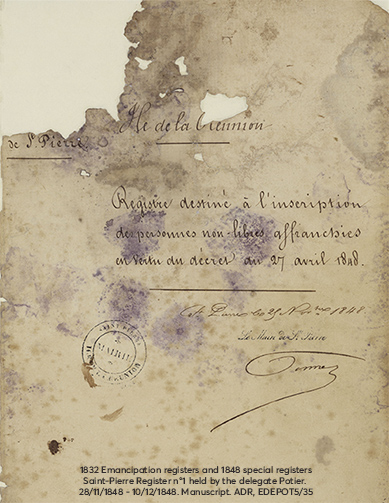

That decade marked the start of collective approval of the fact of slavery, but there remained a conflict of memories maintained through a segmented vision of Reunion’s past, reflected through the image of the places of memory. In fact, the fact of slavery impacted the entire social edifice, bringing about a transformation of an anthropological character and making the whole Reunionese population the heirs of a specific socio-economic system. It is thus the role of historians to carry out the work of writing this past, from which each person can extract the elements of his or her own lineage.