After Portugal, England and Spain, France was the fourth major power to participate in the slave trade between the 16th and 19th centuries. This trade in African slaves, encouraged by the monarchy, provided manpower for French colonists in the Atlantic Ocean (Saint-Domingue, Guadeloupe, Dominica, Martinique, Saint Lucia, Grenada, French Guiana) and the Indian Ocean (Bourbon Island and Isle de France which became Reunion Island and Mauritius and then Mayotte in the 19th century).

The first abolition in 1794 was simply an act of generosity on the part of the parliamentarians of the fledgling French Republic. Parliament member and philosopher Condorcet, a member of the Society of Friends of the Blacks, had condemned this “crime against the human race”. But who could have any interested in such far-flung places? One small commune in Franche-Comté, Champagney, asked for the abolition of slavery in its 1789 list of grievances, but this was clearly one of the rare exceptions. The abolition of 1794 was above all a consequence of the slave uprising in Saint-Domingue, France’s largest sugar-producing colony at the time. With its emblematic leader Toussaint Louverture, this rebellion began during the night of 22nd to 23rd August 1791, a situation then worsened by England and Spain declaring war on France. The Republic’s civil commissioners in Saint-Domingue were Léger-Félicité Sonthonax and Etienne Polverel who, acting without any permission from Paris (and because they needed Blacks to fight the British and Spanish armies), proclaimed the abolition of slavery on 29th August, 1793. Given this fait accompli, the National Convention approved this decision as a matter of urgency, extending the abolition of slavery to all the French colonies on 4th February 1794 (16 pluviôse year II of the Republic). However, this measure was not applied to Isle de France or Reunion Island because the colonists simply rejected the emissaries who finally came to bring the news in 1796, sending them away in their boat! Abolition was also not applied in Martinique, which was handed over to the British by the colonists on 22nd March 1794.

Having studied the revolutionary period in Reunion Island in great detail, Claude Wanquet’s work reveals just to what extent the question of abolition remained at the very heart of the problems facing colonists at that time . The slave revolt in Saint-Domingue haunted the collective conscience, because the event was well-known to both slaves and slave-owners. However, Nicolas Lemarchand, the island’s unofficial representative of the National Convention between 1793 and 1794 and one of the island’s wealthiest slave-owners, took up the abolitionist cause . He did so out of realism, but also out of patriotism, because he was keen not to see the island secede from France, as had happened in Martinique. But following Lemarchand’s claim for compensation for slave-owners, quoting the right to property specified in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, the island’s colonial assembly shared their concern about the position of its representative in Paris on 12th January 1795. They were therefore all the more relieved when, during a visit to the island, Lemarchand made it clear that he had finally given up his role as representative and moved permanently back to France. He continued to assert his abolitionist convictions, while keeping his slaves in Reunion Island, no doubt so as not to disturb the social climate or to create problems for friends who had been faithful to him and who remained on the island.

The two parliamentarians who represented the island at the Convention in 1795, Jean-Baptiste Detcheverry and Pierre Charles Emanuel Besnard, also supported the decree of 16 Pluviôse, Year II across France. However, according to Claude Wanquet, beyond their philanthropic commitment, considerable ambiguity remains, almost to the extent of double standards. On one hand they claimed the long-term importance of abolition, while on the other they insisted on the fundamental importance of ensuring law and order before ever applying the decree in the colony. In particular, they defended the right of colonists to decide for themselves just how best to implement the measure. They therefore welcomed the fact that, immediately after the 1794 decree, commissioners were not sent to implement abolition because, in their view, it would have taken considerable measure and thought to bring about such a social and economic transformation. In fact, they sought above all to ensure the colonists’ autonomy in this decision, for they believed that the realities of life on the island were misunderstood back in Paris. Annoyed by the silence of the colonial assemblies of the Mascarene Islands concerning the abolition decree of 26th January 1796, the French Directory decided to grant extensive powers to commissioners René Baco de la Chapelle and Etienne Burnel before sending them to the island for two years. However, Reunionese parliamentarians were particularly hostile to the choice of this latter person, considered far too blunt. Upon their arrival in Port-Louis on 18th June, the first meeting did not go well: the Directory’s envoys swiftly informed the colonial assembly of Isle de France that they were ready to strictly apply the Constitution of Year III, which would transform both islands into French departments, thus de facto abolishing their colonial assemblies. However, before the question of abolition could even been addressed, the colonists had seized both men by force. The commissioners were then sent off to the Philippines, the aim being to keep them away from Paris as long as possible. In fact, they made their way back to France with little difficulty.

While applauding the dismissal of these commissioners, Reunionese parliamentarians would nevertheless assure Paris that the colony had only the very best of intentions, continuing to proclaim their abolitionist convictions. It was especially a question of asserting their patriotism through the geopolitical importance of ensuring that the two islands remain French during their historical struggle for maritime supremacy against England. For them, the Mascarene Islands could also play a key supportive role in the efforts to keep control of the West Indies. Any colonists who, in the name of maintaining social order, refused abolition, ended up isolating themselves from local elected representatives, and in a certain way from Paris too, given that no elections were organised to re-elect their members of parliament. In fact, since 1796, the island had been experiencing a very difficult economic situation, one which had eventually led to the disintegration of all electoral bodies due to the constant fear of an English invasion. In February 1798, news of Bonaparte’s seizing power of the French Directory had the paradoxical impact of actually frightening Reunion’s anti-abolitionists, as they feared that the abolitionist republicans would return to power. At this time, an insurrection broke out in the south: this was caused on one hand to an announcement that those with unpaid taxes would see their assets seized, but on another hand due to a fear of seeing the colonial assembly allied with the English. Among the insurgents, who eventually surrendered, was openly abolitionist Father Lafosse. Arrested, he was expelled from the island along with the other ringleaders.

Abolitionist fears disappeared when Bonaparte rose to power, as in 1802 he decided to officially continue slavery in places where it had not yet been abolished (i.e. the Indian Ocean and Martinique). Two military expeditions were sent simultaneously to quell the troops of Toussaint Louverture in Saint-Domingue and Louis Delgrès in Guadeloupe who, to the cry of ‘Live free or die!’ refused this return to slavery. Although slavery was finally re-established in a bloodbath in Guadeloupe, Saint-Domingue became the first independent black republic in 1804, and was renamed Haiti.

In 1815, at the fall of Napoleon, the Congress of Vienna, which brought together the victors, decided to ban the slave trade. In fact, slave trafficking continued, but in France the subject was still of little interest. The cause was not without risk in the colonies either: in 1823, Cyrille Bissette from Martinique anonymously wrote a pamphlet entitled ‘De la situation des gens de couleur libres aux Antilles françaises’ (The situation of Freedmen of colour in the French West Indies), which denounced the slave system, demanded civil rights for free blacks, and proposed the progressive repurchase of slaves as well as free schools for those recently liberated. Denounced, he was arrested and sentenced to banishment for life from all French territories. He appealed, but was branded and sentenced to life imprisonment. Following another appeal, he was finally sentenced to ten years of exile from the French colonies.

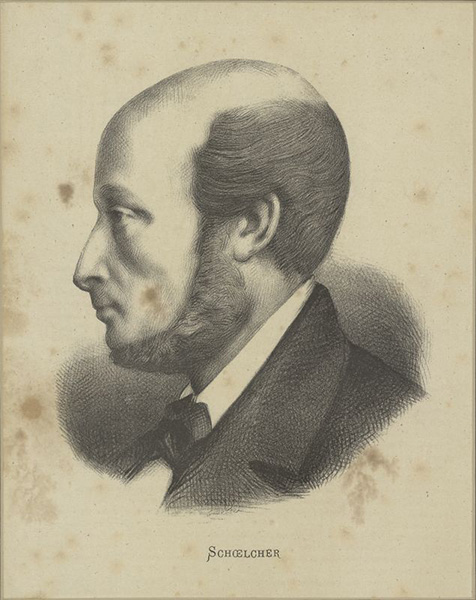

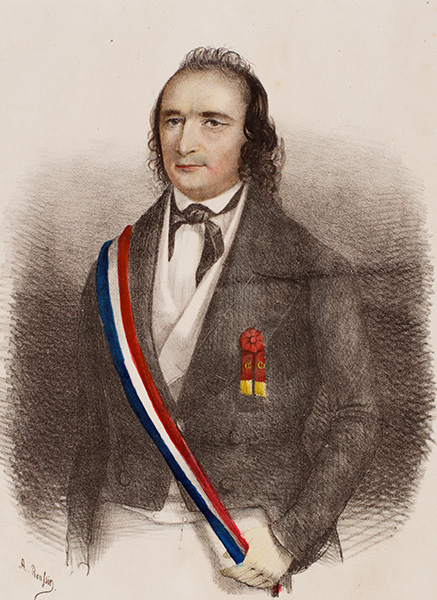

Unlike France, Great Britain saw major public protests in favour of abolition: petitions, distribution of leaflets and even the boycott of goods coming from the slave colonies. It must be said that from the end of the 17th century, there was greater freedom of expression there. This early mobilisation led Great Britain to abolish the slave trade as early as 1807, and then slavery in 1833. Abolitionism was led by William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson, and the latter succeeded in organising two world anti-slavery conventions, held in London in 1840 and 1843. In France, it was through the Protestant movement that the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was created by the Society of Christian Morality. In the 1820s, Abbé Grégoire once again took up his fight against slavery that had started during the Revolution. But it was only after the British abolition of slavery that the French Society for the Abolition of Slavery finally saw the light of day in 1834. Although it held no political sway under the July Monarchy, its members included Lamartine, Tocqueville and Victor Schoelcher. In March 1848, Cyrille Bissette brought together the Society of the Friends of the Blacks, which included personalities such as Alexandre Dumas, both father and son. The leaders of this club invited Victor Schoelcher to come and share his thoughts on abolition, but he refused because he considered the request inappropriate. Schoelcher and Bissette, although bound by the same abolitionist struggle, were thus fiercely opposed.

All dignitaries in Reunion Island were deeply hostile to the abolition of slavery. Considered an abolitionist, Father Alexandre Monnet

was mercilessly demanded by Governor Graëb

to leave the island in September 1847. There were few people within this conservative island society who were not completely resolute or unyielding on the subject. In his work Bourbon Picturesque, writer Eugène Dayot described the realities of hunting down escaped slaves, but while he did not oppose the abolition of slavery, he still refused any hasty application of it until the slaves had benefitted from a certain level of education. Close to the Franco-Créole movement , he defended the freedom of the press so that the conditions of emancipation could be discussed openly. Also seeing that abolition was inevitable, Land Registrar Louis Bret proposed an unsuccessful project in 1841, seeking to facilitate the transition in a way which was both progressive and well-prepared . He thus suggested, along with the complete end to the slave trade, a way out of slavery through the embetterment of former slaves’ lives. Sully Brunet, designated as the colony’s representative in Paris in 1830, also close to the Franco-Créoles and strongly opposed to the island’s pseudo-aristocracy symbolised by the Desbassayns-Villèle family clan, suggested a staggered emancipation through to December 31st, 1859. Out of pragmatism, he felt that if colonists hoped to receive compensation, it was absolutely vital that they participate constructively in the debate, rather than their systematically negative responses to all requests for consultation from Paris.

The proclamation of the Second Republic in February 1848 paved the way for the second abolition of slavery across France’s colonies. However, this announcement was not linked to any humanitarian act – it was the fear of slave insurrections in Martinique and Guadeloupe that prompted the provisional government to follow Victor Schoelcher .

By 1840, Schoelcher’s position had also shifted. Having originally defended a progressive abolition lasting forty to sixty years in his 1833 work entitled De l’esclavage des Noirs et de la législation coloniale, he now rallied to the idea of total and immediate emancipation . When François Arago, Minister of War and the Navy, organised an abolition commission, he entrusted its presidency to Schoelcher (who was careful not to involve Bisette). Abolition was finally decreed on 27th April 1848, providing for compensation for the colonists and a minimum period of two months for its application. Schoelcher’s proposal to compensate the slaves as well and to give them a plot of land was rejected by the provisional government. However, before the Republic’s Commissioners could arrive in the West Indies, slave revolts there made abolition definitive on 23rd May in Martinique and 27th May in Guadeloupe. In French Guiana, it was announced in accordance with the planned timetable, on 10th August.

In Reunion Island, the Commissioner of the Republic Sarda Garriga proclaimed the abolition of slavery on 20th December.

The key aim was to maintain social order: ‘new Freedmen’ were obliged to have a contract of employment or risk being declared vagrants and then taken to forced labour sites. In fact, the island’s slave owners anticipated the consequences of abolition on the workforce at a very early stage. As soon as January 1848, colonists were discussing the need to bring in workers, with some politicians even talking about the possibility of recruiting Irish workers . On the same day that abolition was proclaimed, on 20th December, a ship arrived loaded with recruits. Moreover, Sarda Garriga accepted the slave owners’ request to finish cutting the sugar cane by delaying the official announcement until 20th December, but above all, faced with the unhappy colonists who considered that they would have insufficient cash flow to pay for the wages planned the Freedmen, he chose to reduce the value of a month’s work by two thirds. The Freedmen thus found themselves consigned to poverty, obliged to honour their contract and banned from all public highways on working days. Colonists were clearly grateful for their own conditions, as they collected 40,000 francs in donations for Sarda Garriga and local councillors allocated him an annual pension of 3,600 francs until his death .

67% of landowners may have owned fewer than 10 slaves in 1848, but while the wealthier landowners had said that they wouldn’t be able to pay the Freedmen properly, Prosper Eve’s work remarks they clearly had the financial means to cover the costs of recruiting Indian and African indentured workers. Between 1849 and 1857, their numbers rocketed by 528%, with the agreed contractual wages rising from less than 200 francs in 1849 to 1,100 francs in 1857 . This recourse to hired labour was in fact justified by cleverly orchestrated press campaigns in order to label Freedmen as lazy, which was unfair given that they had honoured their employment contracts signed at the time of abolition. In the same way, those wielding political power did their utmost to prevent former slaves from exercising their right to vote.

From 1849 onwards, every effort was also made to ensure that any celebrations of abolition of slavery were forbidden in public. It was clear that the island’s slave owners did not wish to honour this day . At first it was voluntarily forgotten by the Second Republic as a result of the creation of Labour Day to be celebrated every 4th May (the anniversary of the proclamation of the same decree), and the commemoration of abolition remained limited to family gatherings of Freedmen. Between 1870 and 1936, there were no official commemorations of 20th December. It was only through the world of the trade unions that this remembrance started to appear in public, thanks to the drive of minor industrialist René Payet , who ran in the legislative elections of 1936 under the banner of ‘the new Sarda’, no less. His newspaper ‘Servir’ featured a column entitled ‘the voice of the slaves’, in which he recalled countless memories about slavery and its abolition. Further references to slavery also came from Gabriel Virapin’s union of labourers, who clearly called for a formal celebration of 20th December. In order to counter this trade unionist, René Payet made sure to prohibit any demonstrations in connection with the commemoration of slavery. It was only when Reunion became a French Overseas Department that the date of 20th December came out of the fenoir , first initiated by the PCF (Communist Federation) led by Doctor Raymond Vergès, and then by the Reunionese Communist Party (PCR), founded by Paul Vergès in 1959. But the esteem held for Sarda Garriga within the communist party is worth noting: in 1945, following his recent election as mayor of St-Denis, Doctor Vergès decided to honour Garriga by naming a public place in his honour. As a result, it was the work of this notable republican and his message of order that was celebrated and not the Freedmen themselves. In 1998, for the 150th anniversary of abolition, the communist mayor of La Possession, Roland Robert, decided to lay a commemorative stele at the foot of tamarind tree under which Sarda Garriga is said to have rested during his tour around the island, undertook to prepare the island for the official announcement of abolition. Since then, the theme of slavery has nevertheless become one of the pillars of the island’s communist culture, seen in the violent political conflict between the autonomists of the PCR and the departmentalists backing Michel Debré. For example, in 1968, while official institutions commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of the First World War, particularly around the memory of Roland Garros, the Reunionese war hero who died in battle in 1918, the PCR organised a people’s celebration for the 120th anniversary of the abolition of slavery . To this end, they highlighted the ‘revolutionary’ poetry of Leconte de Lisle, whose birth 150 years before was also being celebrated. In his 1846 work Sacatove, the party identified praise for escaped slaves and resistance in the same way that anti-colonialist battles were fought around the world and, by extension, their own struggle for democratic and popular autonomy on the island.

The date of 20th December was finally marked publically in 1983 by the government of François Mitterrand, allowing each of the French overseas territories to officially celebrate the date of the abolition of slavery in their own way. On 10th May 2001, French parliamentarians then recognised slavery and the slave trade as organised by Europeans as a crime against humanity and, since 2006, 10th May has become the date for which all French people commemorate the long history of the slave trade, slavery and its abolition. The people of Reunion now have two dates to commemorate the abolition of slavery. However, there are still political issues at stake around what some prefer to call the ‘fèt kaf’ and what the Regional Council of Reunion has, since 2010, decided to celebrate as the ‘Festival Liberté Métisse’.