The most influential of these many essays was L’histoire philosophique et politique du commerce et des établissements des Européens dans les deux Indes (The philosophical and political history of European trade and settlements in the two Indies) by Abbé Raynal, to which Diderot contributed.

And in 1788, following the English model, Brissot founded the ‘Society of the Friends of the Blacks’, which included many notable personalities such as Mirabeau, Condorcet, La Fayette, Siéyès, and Abbé Gregory…

However, while Raynal did not hesitate to call for a ‘Black Spartacus’ who would free all slaves from their chains, the Friends of the Blacks demanded above all the abolition of the slave trade and the granting of political rights to Freedmen of colour, postponing the overall emancipation of Blacks to an undetermined date in the future. The general public themselves felt little concerned by the question of slavery, revealed by the mere handful of complaints registered in the 60,000 documents that remain from this period.

In Bourbon, even if some ‘sparks of philanthropy’ had indeed crossed the seas, the vast majority of colonists were fundamentally hostile to the abolition of slavery, considering, as the civil commissioner Burnel would later write, that “the negro, the horse, the ox and the donkey are indistinct, …and are animals that nature has trained for their use”.

The Constituent Assembly adopted a position on slavery that can be described as ‘tentative’. It is true that in August 1789, it enacted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. But some people considered that this declaration should be reserved exclusively for Freedmen, and following its decrees of 8th and 28th March 1790, the assembly placed colonists and their properties ‘under the safeguard’ of the Nation, which implicitly guaranteed the continuation of slavery. Local authorities had the right to propose measures that would thus ‘ensure the conservation of colonial interests’.

In May 1791, the Assembly was rocked by debates following the executions in Saint-Domingue of Ogé and Chavannes, two spokesmen for the Freedmen of Colour. On this occasion a representative of Martinique, Moreau de Saint-Méry, was forthright in demanding that slavery be officially included in the future constitution. Thanks to a most lively reaction from Robespierre, this proposal was annulled, but in the first constitution voted by France in September 1791, colonies were not included at all, thus maintaining the status quo.

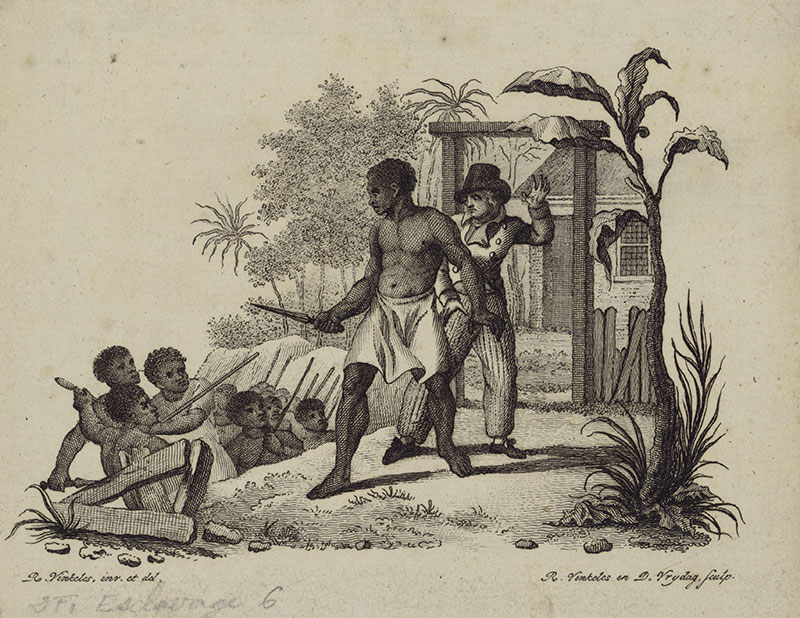

However, a dramatic event turned things upside down completely : the great slave insurrection of Saint-Domingue, which broke out during the night of 21st-22nd August 1791 [ill. 4], causing a great deal of fear across Europe.

In order to restore order to this large American colony, Parliament sent three civilian commissioners to Saint-Domingue, who immediately on arrival confirmed the continuation of slavery. However, overwhelmed by a civil war whose violence was exacerbated by the participation of both the Spanish and the English, these commissioners soon saw that the only way to save French authority was to announce the liberation of all slaves. This was first proclaimed by Polverel in the western part of the island on 27th August 1793, then by Sonthonax on 29th August in the north. To justify their decision they sent a committee to the Paris Convention made up of a white man called Dufay, a Freedman called Mills, and a black man by the name of Bellay, himself a former slave.

After many ups and downs, the three men were finally met by the Convention at its meeting on 16 Pluviôse, Year II (4th February 1794) and Dufay urged the Assembly to approve the policy applied in Saint-Domingue. After spirited speeches from Levasseur (from Sarthe) and Lacroix (D’eure-et-Loire), the Convention decreed “that slavery be abolished throughout the territory of the Republic”.

But once this great moment of enthusiasm had passed, while abolition was enforced in Guadeloupe by Victor Hugues, and then in French Guiana by Jeannet-Oudin (a nephew of Danton), the Convention was slow to take steps to implement it in its eastern colonies. This delay was due, at least in part, to the subtle and tenacious obstruction of parliamentarians in Isle de France, Jean-Jacques Serres and especially Benoît Gouly. A tireless slanderer, Gouly used all kinds of hypocritical abolitionist professions of faith, developing all the arguments likely to justify a deferred application of February’s decree across the colonies.

Roughly speaking, all of these arguments can be found in a host of documents from the revolutionary period, written not only by settlers and colonial authorities, but also by a number of politicians. It is worth noting that maintaining French power over its colonies was vital for the country’s wealth and military power, colonies that had always proved their affiliation to France. This was particularly the case of the Mascarene Islands, the ‘keys to the Indian Sea’, who had fought valiantly against the English. Abandoning them or creating unrest there would only play into the hands of the counter-revolutionaries and the English, which would be the case if the Blacks were suddenly freed, released in the state of ignorance and inexperience in which they found themselves. The Blacks would be the first victims to fall foul of such an imprudent policy, and would be sure to sink into violence and famine. The conclusion of this was that while philanthropy and justice justified the abolition of slavery, these very same virtues required that this abolition be carried out only very gradually and with great care. This is precisely what the rulers of the eastern colonies did. In Bourbon, by granting political rights to the Freedmen even before the National Assembly had, they encouraged an increase in the number of emancipations. And above all by suspending the slave trade by a decree of 7th August 1794, most probably adopted as a precautionary sanitary measure against the risk of a new smallpox epidemic, but skilfully presented as a humanist measure because it had been voted just a few weeks before the island became aware of the February decree.

On the whole, between 1791 and the end of 1794, Bourbon remained socially very calm. This was apart from a brief commotion caused by a certain agitation in the garrison, behaviour deemed too favourable to Lafosse’s Blacks, who was a parish priest and at one time mayor of Saint-Louis, and confusing preparations of a ‘conspiracy’ in June 1792 by a few poor whites acting as spokesmen for the Freedmen. Then, on the pretext that the February decree had not been officially sent to them, the colonial authorities imposed silence on the subject. And very few were in favour of its application, except maybe a few poor white men in Saint-Joseph who, according to local dignitaries and Lemarchand (the former unofficial representative of the island at the National Assembly), were excused for their ‘simplicity’. And even if it seems certain that the slaves were aware of the existence of this decree, the vast majority of them remained silent.

In France, a long debate took place in February 1795 related to measures to be taken in the Mascarene Islands but little ever came of it. And a first commission planned for the eastern islands was quickly cancelled.

However, after the fall of Robespierre, the clearly stated will of the Thermidorian Convention to adopt a new Constitution led to a new status for the colonies defined in a very long report by Boissy d’Anglas of 4th August 1795: assimilation. Consequently the Constitution of 5 Fructidor Year III (22th August 1795), whose avowed objective was to ‘bring the Revolution to a close’, gave Reunion Island the status of French Department. This led, quite logically, to two commissioners being given full powers (in theory) and assigned with the job of bringing the Constitution to the Mascarene Islands.

These commissioners were René Gaston Baco de La Chapelle who, in 1793, had been particularly well known as mayor of Nantes for his resistance to attacks in the Vendée, and Etienne Laurent Pierre Burnel who had lived for three years in Isle de France at the start of the Revolution, working in various professions (journalist, secretary of the colonial assembly and lawyer), but not always leaving the best impressions on fellow colleagues. They arrived in Port-Louis on 30 Prairial Year IV (18th June 1796) at the head of a veritable armada, with 4 frigates commanded by Rear Admiral Sercey and 780 soldiers commanded by General Magallon (formerly de La Morlière). But after three days of tortuous discussions, the crowd of settlers sent them off on a corvette leaving for the Philippines. This operation had obviously been orchestrated by old governor-general Malartic, and took place without any intervention from the expedition’s soldiers, sailors or even their heirarchy.

This whole affair only took place in Isle de France, but the colonial assembly of Reunion Island immediately and vociferously approved its conclusion. This was confirmed in long addresses to the National Assembly in July-August 1796 and April 1797, repeating all the arguments against a brutal liberation of the slaves mentioned above. Henceforth the island, while strongly displaying its loyalty to France and the Republic, lived in a situation of de facto autonomy, determined to reject (by force if necessary) any attempt to apply abolition there.

When the agents returned to France at the end of September 1796, there were many discussions on the reasons for their failure and the possible means of remedying it. But nothing had been decided when, in the elections of April 1797, the Clichy party, made up of notorious royalists and colonialists such as Vaublanc (a former colonist) or Barbé-Marbois (former governor of Saint-Domingue), led a vigorous anti-constitutionalist and anti-abolitionist campaign that lasted a few months. But this party was in turn swept away by the coup d’état of 18 Fructidor an IV (4th September 1797) which advocated the development of a new French colonial policy which was characterised (among other things) by great expansionist ambitions in India. An active ‘neo-Jacobean’ drive would also mark the first months of 1799: this was highly favourable to abolitionist ideals, all the more so given that the Society of Friends of the Blacks had returned.

A new mission was planned in the spring of 1800, entrusted to Admiral Villaret-Joyeuse and Lequoy-Montgiraud, who were given secret instructions to gradually implement the original February decree in the eastern colonies. This never happened, but in October 1800, Cossigny de Palma (the island’s former interim representative in Paris), arrived in Isle de France. He was appointed the new director of the Powder Mill, and was obliged to grant various benefits to the slaves who worked there, including a salary. This measure was immediately appealed against, and vehemently refused by local authorities both there and in Reunion Island, unhappy that this would surely be a first step towards the application of the ‘fatal decree’.

During the period 1796-1801, Reunion not only approved anti-abolitionist measures taken by its neighbouring island but often even outdid them. To the point of imagining a unilateral declaration of independence (towards the end of 1799 and beginning of 1800), albeit a temporary independence until the monarchy had been re-established in France. This monarchy had been rejected by the colonial Assembly after much debate, and had been affiliated to that of England. At the same time, repressive social measures increased across the island: emancipation was first limited and then suspended; it was forbidden for a Freedman to take the name of his former master, even if it were his natural father; mixed marriages, i.e. between people of different races, were forbidden; the slave trade was re-established.

All this was accompanied by a considerable toughening of sanctions brought upon on any pro-abolitionist demonstrations. One example was the expulsion of a newly-arrived garrison of soldiers, who were exiled to Batavia for being too familiar with slaves. Another example was the ‘trigger-happy’ execution in November 1799 of at least five black men from Sainte-Rose, who had been accused of preparing a widespread massacre of the whites, backed up by vast numbers of supporters who were capable of spreading a ‘salutary anger’ throughout the rest of the slaves.

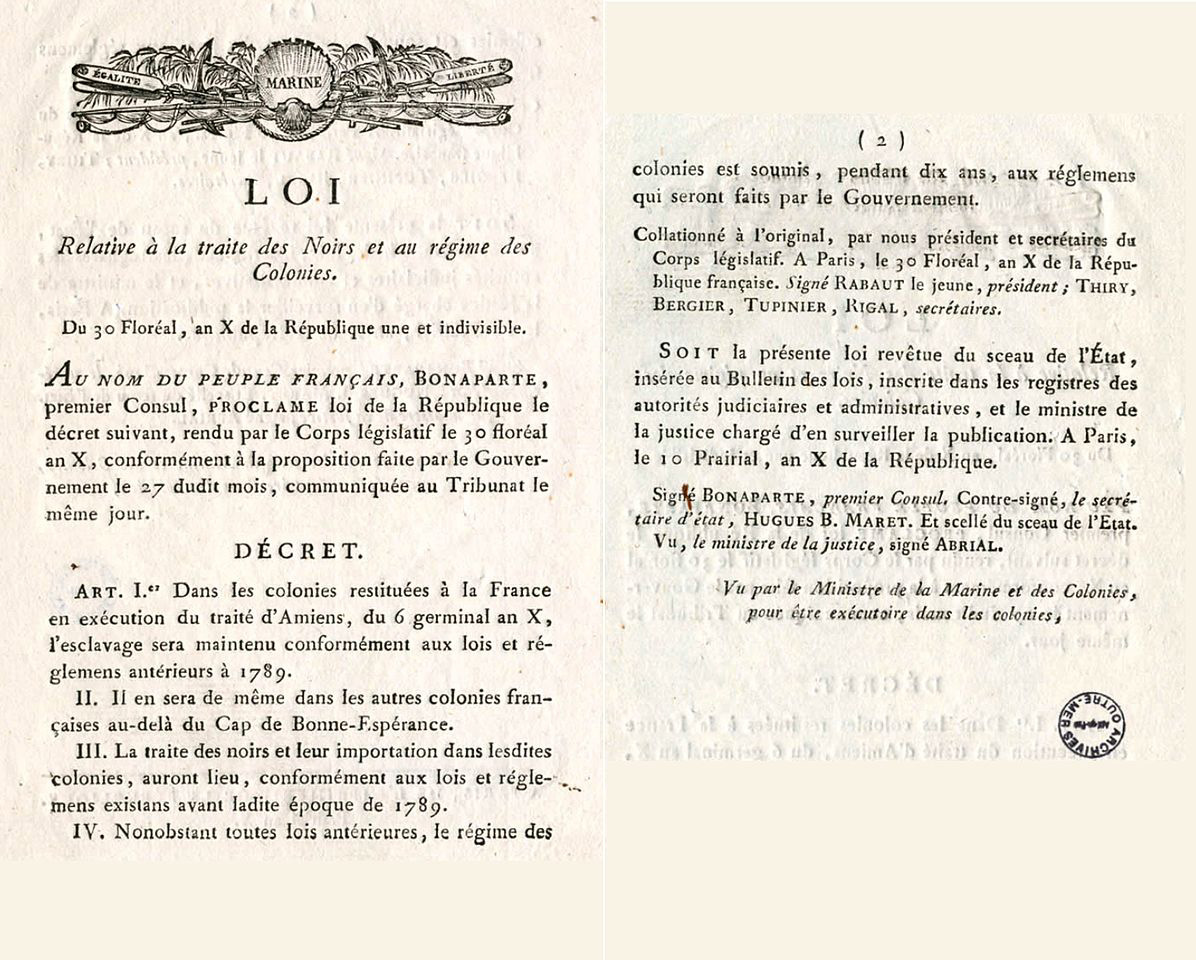

The crisis came to an end when Bonaparte, no doubt influenced (as he later claimed) by “the squabblings of the colonial party” but above all driven by fundamentally racist personal convictions, decided to re-establish slavery by the law of 30 Floréal, Year X (20th May 1802). Decrès, his new Minister of the Navy (who had lived for several years in Isle de France) recommended to Decaen (who had been appointed governor-general of the eastern colonies) to “carefully maintain the distance between colours on which our national existence is based”.

And thus, a regime of military dictatorship and social regression was then established in Reunion Island, far worse than that which had existed on the island at the end of the Ancien Régime. It carried the approval not only of local dignitaries but certainly also of the majority of colonists, who cheerfully sacrificed their autonomist political aspirations in order to maintain their social privileges.

As for any hopes of abolition, it seems to have been expressed throughout the revolutionary period, but essentially by the slaves themselves, with a few libertarian gestures and/or words and a significant increase in marronage (escaped slaves), without ever any real collective demonstration on a scale comparable to those in Guadeloupe or Saint-Domingue, which became Haiti, the first black republic, on 1st January, 1804.