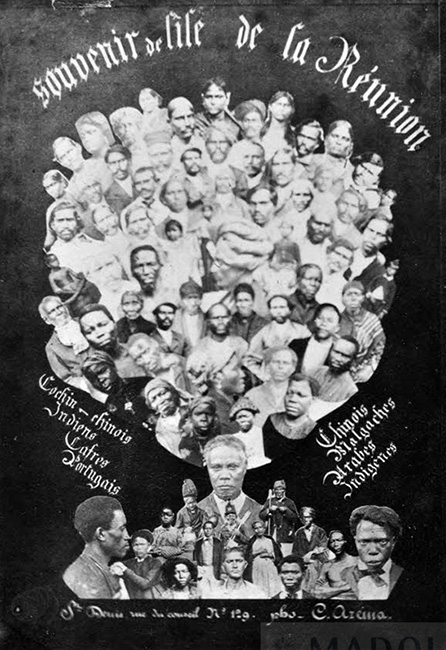

Indentured labour was the system that replaced slavery following the 1833-34 abolition across British colonies and 1848 for colonial France. It was a worldwide phenomenon, displacing more than three million people, mainly from Asia (1.5 million Indians , 500,000 Chinese) and Africa. A fifth of these people were shipped to the sugar-producing Mascarene Islands (around 200,000 to Reunion Island and 462,800 to Mauritius).

One of the characteristics of indentured labour in Reunion Island was just how early it was introduced, during a period when slavery was still legal. While Mauritius was a pilot for colonial Britain’s Great Experiment in 1834 , the only place in the world where the testing of 3,000 indentured labourers working alongside slaves took place in Reunion. In April 1828, at the colonists’ request, the schooner La Turquoise delivered fifteen ‘telinga’ workers, brought in from Yanaon, India. They were the sugar industry’s first indentured workers .

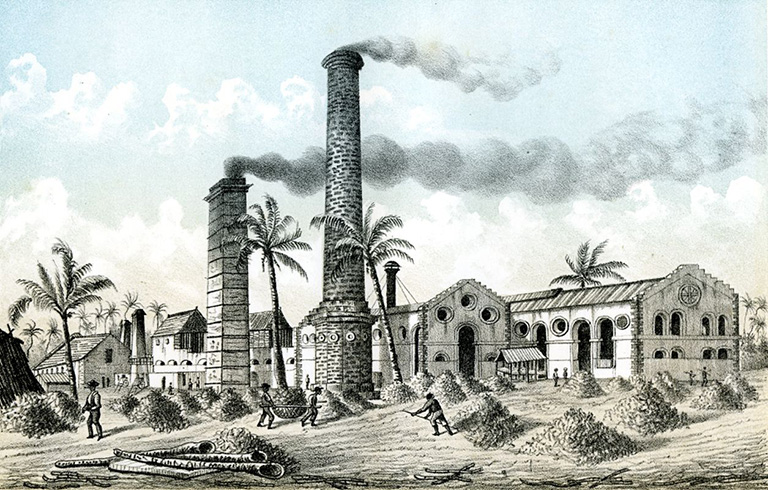

Sugar’s rising popularity across Mainland France and the planned end of slavery were the two key factors that attracted these new workers. With the loss of France’s main sugar colony, Saint-Domingue , and the catastrophic cyclones of 1806 and 1807 which destroyed the island’s coffee plantations, sugar cane was duly planted, a crop which required a considerable workforce that had to be both inexpensive and, above all, easy to control.

However, the slave trade had been prohibited since 1815-1817, which made it difficult for slavery to continue on the plantations. Furthermore, attacks by anti-slavery societies were indicators that the system was drawing to a close.

And so, an old labour system was reintroduced, one used by the French East Indies Company in the 18th century, making it possible to send Europeans to the colonies on so-called ‘36-month contracts’, but also free workers from elsewhere. In the Mascarene Islands, governors Mahé de Labourdonnais and Benoît Dumas brought in hundreds of Indians or ‘Malabars’ from Pondicherry, specifically because of their technical knowledge and skills.

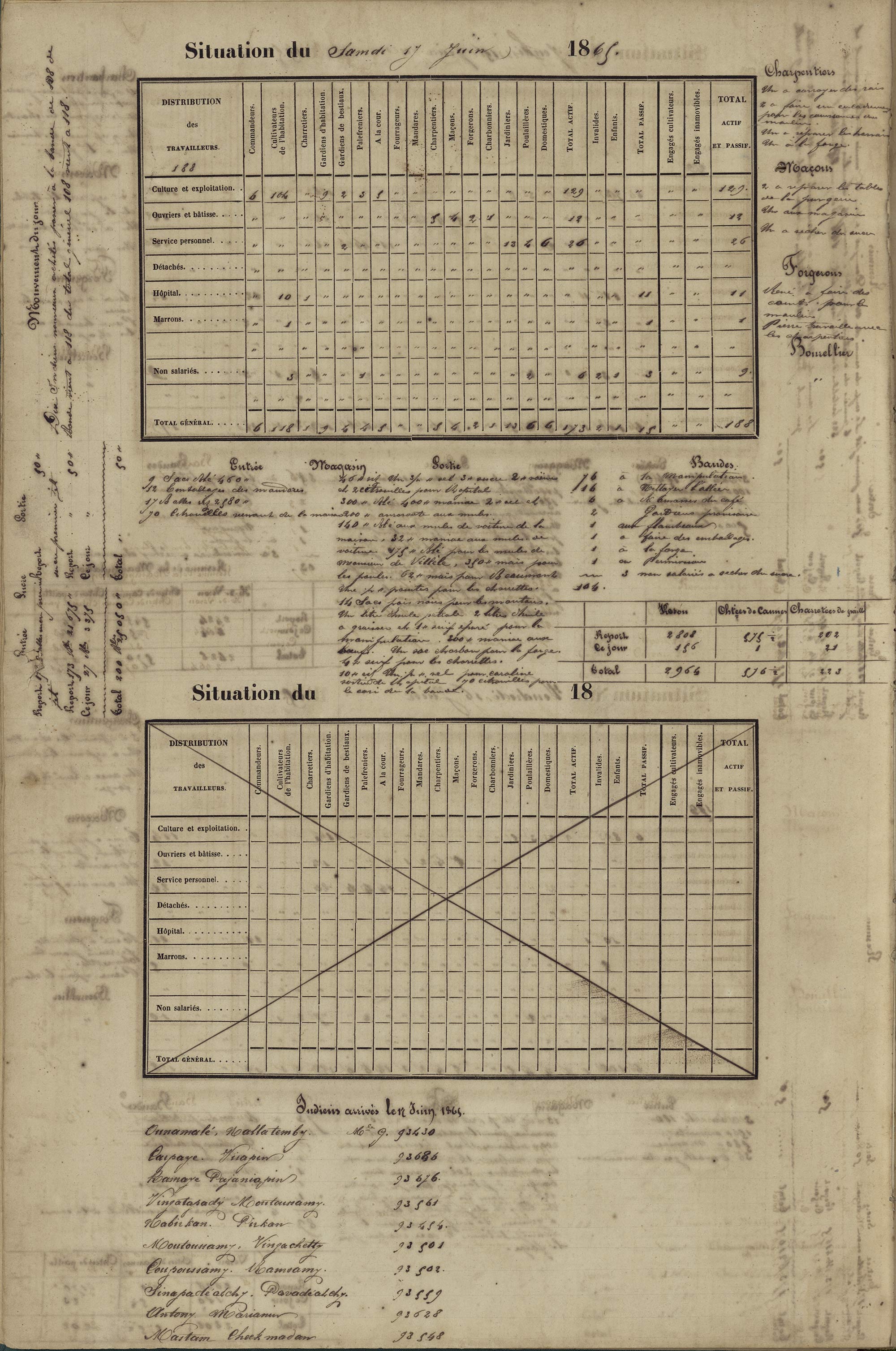

Emigration from India was not constant, and lasted over three specific periods: from 1828 to 1830, indentured workers came from Yanaon, the 1848 to 1860 period concerned emigration from the French trading posts of Pondicherry and Karikal, and from 1860 to 1885, workers came in from the British territories of Calcutta, and then from Madras, Pondicherry and Karikal. Every time that these migratory flows from India would slow or stop, recruiters would turn to other regions of the world: China from 1844 and, after 1848, the east coast of Africa, Madagascar, the Pacific islands, Indochina and Comoros. The final wave of indentured workers came in from Rodrigues Island between 1933 and 1937.

In ‘Le lazaret de La Grande Chaloupe: quarantine et engagisme’, [Michèle Marimoutou-Oberlé].

Department of Reunion, 2017. P. 94 ».

Collection: Historical Museum of Villèle.

Indentured labour was a system that spanned more than a century, leaving a lasting impression on the island, altering the make-up of the population and modifying the island’s existing religious and cultural framework. It represented a major contribution which has shaped the Reunion Island of today.

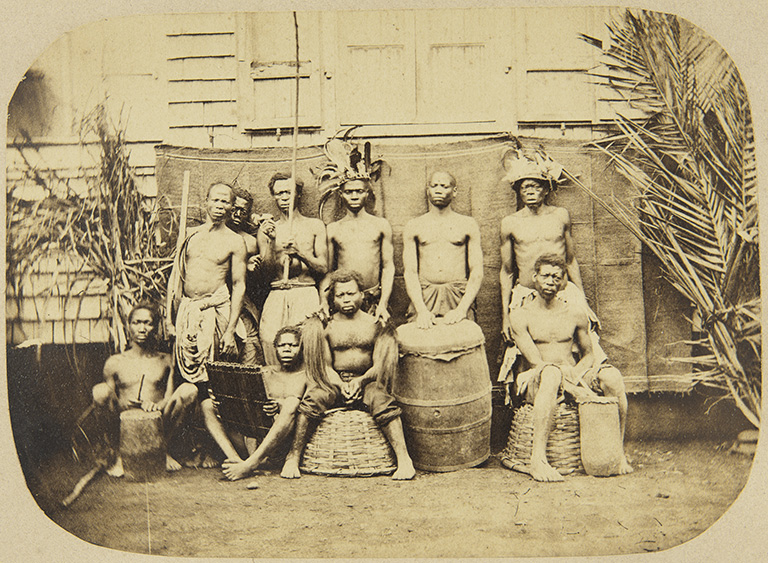

Azéma, Constant. 1871-1877. Photograph.

Collection: Museum of Decorative Arts of the Indian Ocean.

The slaves who were brought to the island were marked by the stigmatising traumas resulting from their capture by slave hunters, their arduous march in chains along paths that were littered with the corpses of those who had not survived, all the way to the major slave markets. Following that came the shame and impotent anger resulting from their bodies having been displayed for sale, a further march to the shore and an ocean which would forever separate them from their homeland and their ancestors, with no hope of return. When they landed, weakened and exhausted, having survived the deadly voyage spent chained up in the holds of slave ships, they would become the property of unknown slave masters who would rename them and bear the right of life and death over them. While younger ones lost all their bearings, the older ones would try to keep the memories of their language and ancestral rituals alive. All of them had to adapt to a gruelling life on the plantations, or else run away and risk inhumane punishment upon recapture (branding with a red-hot iron, ears or fingers cut off…) or even death.

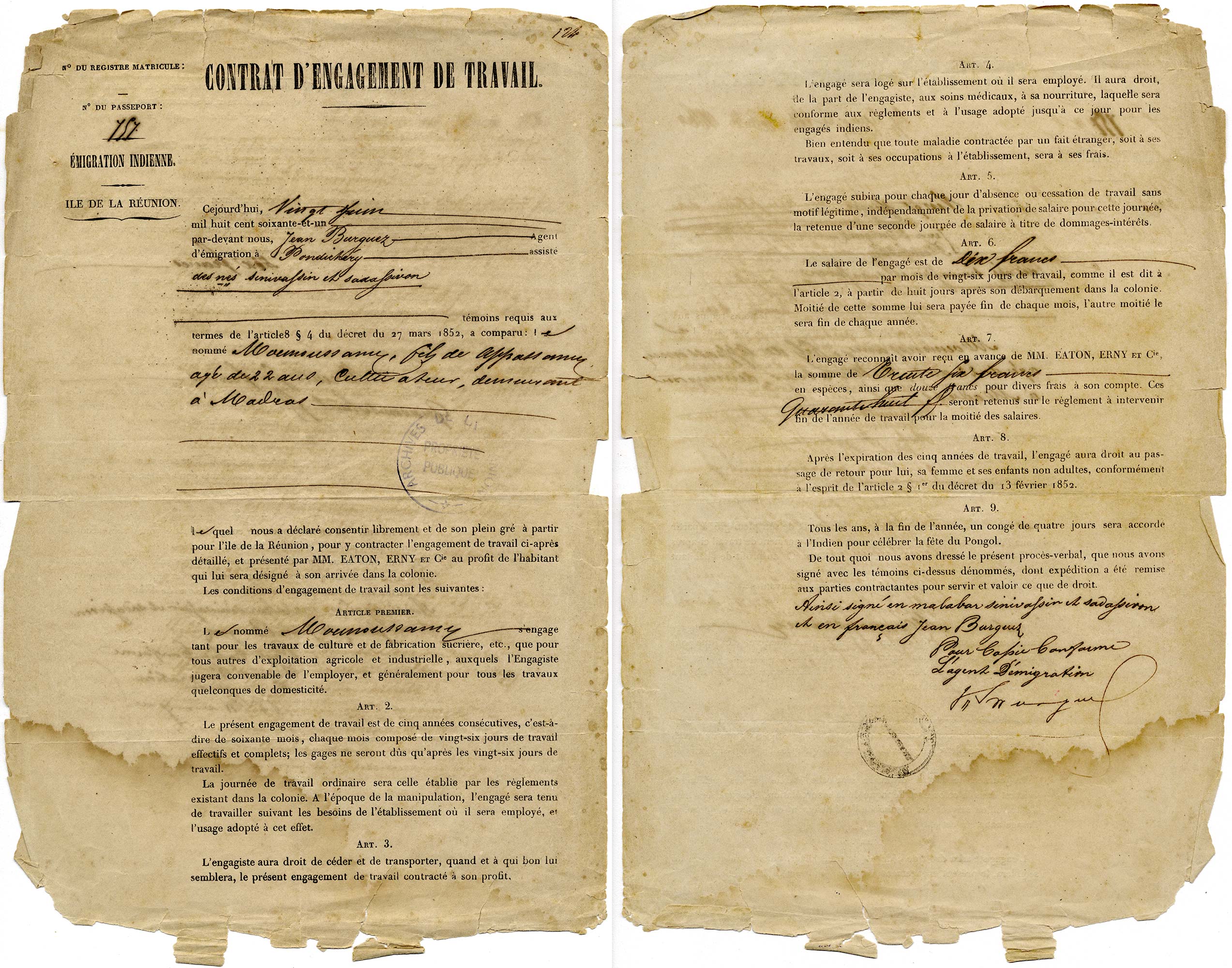

By comparison, as free workers, most indentured labourers actually chose to cross the oceans and work elsewhere, and their status was recognised in the 18th and 19th centuries. As such, they were able to sign a written contract, the details of which they had initially been made aware. Everything was agreed in advance: the working hours over three years in 1828, then five years; their monthly salary and the obligation for their employer to house, feed, care for and clothe them. Above all, they were reassured of their right to practise their religion and, at the end of their contract, to be repatriated if they wished. All these conditions were specified during every major period of Indian indentured labour and were valid for all workers, in accordance with the Franco-British Conventions of 1860-61.

As free men, indentured workers were allowed to keep and hand down their names. These were recorded on the ship’s lists and then, upon arrival, in the colonial and town registries: the name given on departure was generally their original name, but not necessarily. It was written on their employment contract and passed on to any children born on the island. Most descendants of indentured workers bear the name of a female ancestor, as she was the one who would declare the new−born child. In the 19th century, it was rare for parents to be married according to French law, as couples would just settle for a religious ceremony.

Indentured workers owned everything they managed to accumulate and were allowed to pass it on to their children. But above all, public holidays and days off for religious reasons were specified in their contracts. In line with the agricultural calendar followed by the sugar estates, religious ceremonies were all grouped together at the end of the year, in late December and early January when the factories had closed. For the Indians, it was the celebration of Pongol, which marked the beginning of the rice harvest, and for the Africans, festivities known as the ‘fête cafre’.

The legal status of an indentured worker was therefore nothing like that of a slave, who was a mere object belonging to a master and, as such, could not possess or hand down anything, not even a name that was not even his own (having been replaced by a simple first name); not even his religion, which was no longer his original one, Christianity being the strict rule. He could not defend himself in court, and had to be represented by a ‘master’, necessarily a free man, who would speak in his name.

However, indentured labourers worked under conditions laid down in the decree of 27th March 1852, and could not negotiate anything beyond this, whether their salary or contractual conditions. Because of this, their status did not fall under the principles of ordinary French law governing the hiring of services, but under a particular form of employment known as ‘forced’ or ‘restricted’ employment .

In 2001, Sudel Fuma proposed that the French word ‘engagisme’ be replaced with the word ‘servilisme’, in order to distinguish between the status of Freedmen who had been forced to work after 1848 and that of immigrant workers, considering that this concept better showed that ‘indentured workers were not free and were subject to a system, but were not slaves in the legal sense of the term’. This proposal never gained traction, but it at least highlighted ‘the fraudulent nature of the contracts’, so characteristic of indentured labour from Africa and Madagascar before 1860.

As migratory waves from India to Reunion Island began to slow, those looking for indentured workers would turn to the east coast of Africa. In 1850, any Africans recruited had to be individuals who had not experienced slavery, and held a status known as ‘already free’. However, from 1857 onwards, this façade fell and they were treated as before: slaves who arrived on the coast were bought and then freed, before being hired for a minimum of ten years.

In Zanzibar, the last wave of recruitment was led by Viscountess Jurien in 1858, at the request of Governor Darricau: during the night of 28th October, the Pallas left with 200 ‘blacks ’ , but delivered only half of them on 16th December, the others having perished during the voyage.

This similarity with the slave trade was such that the British government of India ruled that, as British subjects, any Indians had to be considered as already free before being recruited for France’s sugar-producing islands. More than 34,000 African and Malagasy indentured workers were recruited in this way.

Even in this case, indentured workers were allowed to keep their names (which they were allowed to pass on) and were free to practice any religion they wished.

Any studies of indentured workers’ living conditions on sugar estates require an examination of all kinds of archives. However, most documents concerning indentured workers (such as reports, court records or the minutes of enquiry commissions) focus on the dysfunctions of the system. This significant bias makes it impossible to fully appreciate the daily lives of most workers, as most of these documents only show the dark side of indentured labour and the difficult situations faced by those working on specific sugar estates. Comparative studies have yet to be carried out in order to fully understand the living conditions of indentured workers compared to other labourers, or to find out the exact percentage of indentured workers whose contracts were not respected .

In ‘Notice sur la Réunion’, A. G. Garsault, Paris: J. André, 1900. Pl. XXIII”.

Collection: Historical Museum of Villèle

Those recruited from the Pacific Islands had no idea of their final destination , and as for the Vietnamese recruited from 1863 to 1866, they were more likely to be political exiles . Others were misled about the real conditions of their contract: in 1933, upon discovering just how far their reality differed than the one they had imagined, labourers from Rodrigues Island refused to work, deserted their camps and ended up being repatriated by the governor.

In fact, the coolie-trade (the recruitment and transport of indentured workers) was highly profitable, enriching ship-owners, emigration and immigration companies, and recruitment agencies in ports of embarkation.

Locally, there was considerable legislation governing the rights and duties of indentured workers, including the decree of 13th February 1852, and unions were set up with the task of easing certain difficulties. Despite this protection, there were recurrent cases of employers delaying wages (or not paying at all), as well as pay-cuts of dubious legal standing. As early as the 1830s, complaints about the non-payment of money owed to families in India were rife; in 1877, a report of the international commission which analysed the situation of indentured Indian workers showed how various legal means were utilized to reduce wages, resulting in labourers having to almost work for free . And the very reason why they had agreed to a five year contract was so that they could save sufficient money needed for a more decent life.

On top of this, indentured workers were not free to move as they pleased. A formal document or ‘pass’ signed by the landowner was needed for anyone wishing to leave the grounds, without which they could be arrested as a vagrant or a deserter, and duly punished. Sanctions were converted into free working days added on at the end of their contract; furthermore, any days absent were punished by two extra working days, regardless of the reason.

Living conditions of indentured workers were difficult, due to the unsanitary conditions in camps which had few female labourers, but also due to the high work rates that increased during periods when the sugar cane was being harvested and processed.

Indentured labour in Reunion Island earned the reputation of being less attractive than elsewhere, even at the end of the 19th century. It is estimated that 25% of the Indian indentured workers died on the island and 25% were repatriated to their ports of origin, often those who were no longer able to work and for whom the colony no longer wished to care. As for the indentured workers from Africa who arrived after 1848, only 4.7% of them left .

Most of the Mozambicans who came at the end of the 19th century, the Chinese who arrived on the Erica in 1901, and those arriving from Madagascar in 1922 and Rodrigues in 1933 did not choose to extend their contracts.

For those who stayed behind, and whose children born there would become French citizens (according to the law of 1889), their break with indentured labour depended largely on their morals and their ability to support themselves. While a certain number of Indians took advantage of the fragmentation of large estates, in turn acquiring their own land, the majority of former indentured workers continued to work as farm labourers or share-croppers, eking out a miserable existence until the middle of the 20th century.

Indentured labour is not slavery: the Taubira law of 10th May 2001 states that only the slave trade in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans and the enslavement of ‘African Amerindian, Malagasy and Indian populations’ in these regions is a crime against humanity. However, article 4 deals with the conditions of indentured workers, namely that the public holiday was not only created to commemorate the abolition of slavery, but also ‘the end of all indentured contracts signed following said abolition ’. However, no one today associates 10th May in Mainland France or 20th December in Reunion with the end of indentured labour