Performed clandestinely on coffee or sugar cane plantations during the 18th and 19th centuries, it declined in the 20th century for reasons that are still obscure, sinking into oblivion due to the indifference of the Reunionese intelligentsia . While a few protectors of Creole civilisation were affected by its disappearance, the general public were unaware of it, and no serious action was taken to revive and safeguard this artistic ancestral combat dance.

Whether ashamed of a past marked by slavery or weakened by the break-up of society due to the rapid westernisation of Creole life, questioning the practice of Moring is at the heart of this debate . It is true that in the 20th century, between the 1950s and 1990s, Reunion Island experienced a social phenomenon which is still little known but which is of essential importance: the technical, economic and socio-cultural changes of the post-departmentalization years which plunged the island into a society based on consumerism and leisure. Like Maloya, Moring is no longer part of mainstream culture, today only surviving in the collective subconscious of the Reunionese . Passed down from generation to generation, it became no more than a distorted and ghostly memory. Those bearers of knowledge, often elderly people overwhelmed by the pace of technological innovation, hardly dared to hand down this cultural heritage, which was very different from the reasoned culture of the 20th century. Like the entire western world that has lived through the post-industrial era, Reunion lost touch with its cultural history during the 20th century . Those who grew up in the sixties knew nothing about the combative significance of Moring, due to a lack of communication between them and their parents. Today, an awareness of this divide and a desire to rediscover their roots have led young people to reject contemporary models, and this need for identity in a society stifled by Western models has given Moring a second chance, but also other Creole cultural values previously hidden away by colonial history. Historical and ethnographic research will therefore lead young people to listen to their traditions, which is indispensable for understanding the meaning of the values deeply rooted in the collective subconscious of the people of Reunion.

What is Moring? What is its role in Reunionese history? How did it develop and why did it fall into oblivion in the 20th century?

Like many other Reunionese traditions, the art of ritual combat known as Moring first originated in Africa and Madagascar where it was performed well before the colonisation of Bourbon Island, which became Reunion Island in 1848 . From a strict etymological point of view, the term Moring comes from Malagasy. ‘Moraingy’ is a martial art that was widely practised across Madagascar in the 17th century, notably during the period of King Andrianapoimerina. A ritual contest of virility between men, it takes place at celebrations and circumcision ceremonies . The ritual is similar to Reunionese Moring, but it differs in the style of combat and the blows dealt by opponents. Much like Moring in Reunion or Comoros, Malagasy Moraingy always begins with a challenge. Despite the varying geographical groups (Madagascar, Comoros, Reunion Island) this shared ritual is proof of the common origin of this artistic combat: the same initial challenge is repeated in all three countries. One competitor comes out of the crowd to provoke a potential opponent while a team of musicians keeps the beat using drums or, failing that, zinc cans. This challenge can also be expressed by war cries. To accept the challenge, another man will step out of the crowd to confront the first fighter.

In Madagascar, ‘Moraingy’ fighters do not use their feet and are not allowed to hit sensitive areas. In both the Comoros Islands and Mayotte, ‘Mrengué’ or ‘Mouringué’, involved real blows, which took place in the evening and could sometimes last all night long . As in Madagascar or Reunion Island, the ritual of the challenge took place within a circle to the noise of drums. In Ngazidja, in Grande Comore, another form of physical combat known as ‘Nkodézaitsoma’ was practised on the 26th day of the fasting month of Ramadan, taking place in the form of a bare-handed, no holds-barred fist-fight. Boys would fight first, then followed by women and then men late at night. Unlike ‘Mrengué’ in Mayotte, where a referee would intervene to separate fighters after two or three violent (sometimes fatal) blows, the rules of ‘Nkodézaitsoma’ were more confused and the fight could degenerate into a real brawl. The participants would briefly forget the real meaning of the 26th day of Ramadan or night of destiny, the night when the angel Gabriel shared his divine revelation with Mohammed. Fighting between clans was a way of reminding participants how people lived before Mohammed received this divine revelation.

From the same Moring family as practised by the Reunionese, the ‘Dakabé’ or ‘Diamanga’ still lives on in the highlands of Madagascar. The ‘Diamanga’ mainly involves footwork, as in Reunionese Moring: thus in both forms we have the ‘tsipak’akoho’ (striking with the sole of the foot), the ‘kopola manitra’ and ‘miamboho’ (a slicing kick), and the ‘ambadiha’ (somersault blow). Other Malagasy techniques such as the ‘kapa tokana’ (heel strike) or the ‘dongomby’ – (clashing of chests) are similar to those seen in Moring.

Beyond mere nuances of style, there is no doubt that Moring belongs to the family of Afro-Malagasy martial arts. While Moring came to Reunion via Madagascar, its origins even further back seem to be African, where the art of combat has been practiced since the most ancient times. The indigenous people of Africa, Mozambique or Angola had their own martial traditions before their forced departure for the colonised regions of America or the Indian Ocean. The origins of ‘capoeira’, Brazil’s very own Moring, are African: shipped off to Brazil, slaves from Angola kept a warrior rite known as ‘Batouk’. The Angolans fought by imitating the gestures of animals, and the different blows had visual names such as horse-jumps, monkey- jumps, horse kicks…etc.

Like Brazilian capoeira, Moring is therefore a cultural phenomenon handed down from generation to generation by Afro-Malagasy ancestors over several centuries . Shipped to Madagascar on Arab dhows or to the Indian Ocean colonies by Western slave traders, African slaves brought with them these ancestral cultural values, a way to let off steam and express their identities . Without Moring or the dance of Maloya, these people who had lost their native language and religion would have found themselves in a place with no cultural references at all. In 1714, with 623 white and 534 black Malagasy and Africans living on Reunion Island, one might think that Moring had not yet been developed. The socio-cultural context of the island would change very quickly with the massive introduction of Malagasy and African slaves in the 17th century .

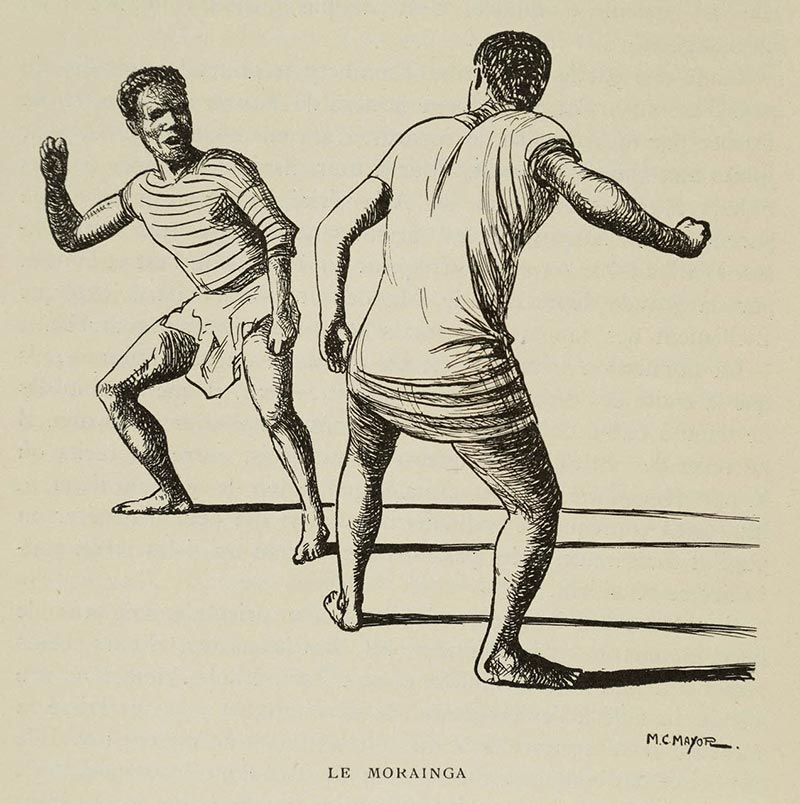

With the application of the Code Noir in the French islands of the Indian Ocean in 1723, the trade in black slaves, especially from Madagascar in the 18th century (many more than those from Africa until 1810) led to more than 160,000 slaves arriving on the island between 1723 and 1810. In need of labour to work in the coffee and spice fields, the plantation economy was the reason behind this forced displacement of Africans and Malagasy, sold as slaves in Reunion Island. Although slaves could not officially practise their religion, they were nevertheless allowed to dance or entertain themselves outside working hours, as long as they did not disturb their masters. Written documents referring to dances or Moring combats are rare and only the spoken word remains to describe this bodily expression of these former slavess . With its own code of precise rituals, it does not seem that this form of Moring has evolved much since its beginnings in Reunion Island. However, depending on the area or period concerned, certain nuances of style have marked the life of Reunionese Moring. For example, an 1839 account gives some vague explanations concerning combats between slaves. According to the writer, each slave “expresses his problems in life through song. However, the dances always end in brawls, with the opponents almost always attacking each other using head butts or punches. The audience goads on the fighters, as they want the fight to be as bloody as possible. Fights don’t stop until one of the two are on the ground” . The illustration of a fight in 1839 shows two combatants in a fighting position more akin to a classic fist-fight than to the Moring combat described in eye witness accounts during the 20th century.

Reservations must be expressed concerning the possible French origins of Moring according to Philippe Bourjon’s work published by the University of Reunion in 1988, Rôle et enjeux, approche anthropologique généralisée . While it is indeed probable that sailors in the French navy, who were adept at savate or French kick-boxing, would hold impromptu dock fights to ‘release the tensions accumulated during voyages’, it is questionable whether these practices ever influenced the martial arts of Malagasy and African slaves . It should be remembered that the social context of the time prohibited mingling between whites and blacks, even if they were the king’s sailors, and any blacks gathering in public would be punished with whips. Whatever the style, any martial artist knows that fighting techniques can only be acquired after a long learning curve and considerable attentive observations of the various gestures to imitate. At the time, the Code Noir separated Blacks from Whites, formally preventing any cultural exchanges between these two groups. Although the techniques of French boxing are reminiscent of those of Moring (particularly the ‘reverse backhand’), any similarity does not necessarily mean that fighting techniques were indeed exchanged. Moring is therefore above all a martial art of Afro-Malagasy origin. Its ancient presence in Madagascar can be explained by the island’s geographical proximity to the African continent. Its populations (such as the Sakalaves of African origin) explain the strong presence of African customs in Madagascar. However, when we know that the slaves transported to Reunion Island were mainly Sakalaves, we can conclude that they were legitimately trying to preserve their ancestral traditions in their new country .

Originally, Moring allowed the island’s black population to assert their cultural identity. An African art, it was mainly practised by those of Malagasy or Cafre origin, except in the 20th century, when it was embraced adopted by the poorer classes of the island’s population. In fact, before slavery was abolished in 1848, Moring was considered as a leisure activity only fit for slaves, and a degrading activity for colonial society – no whites (wealthy or impoverished) would have taken part, as this was considered beneath them. After the official proclamation of the abolition of slavery on 20th December 1848, Moring remained the exclusive heritage of those freedmen for several decades, as their integration into colonial society was slow and arduous .

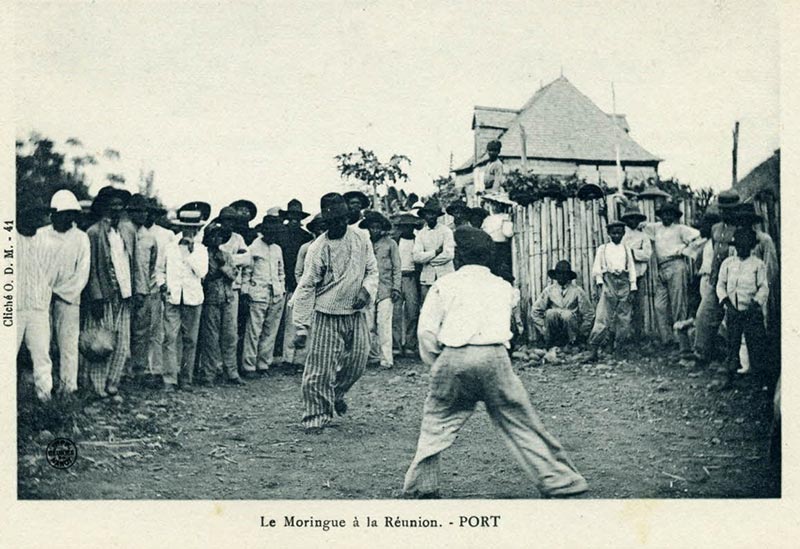

Nevertheless, between 1880 and 1900, the living conditions of the former slaves caught up with those of the lower class Creoles, especially the poor white farmers and the Creoles of colour. While Cafres, Malagasy and Indian immigrants still represented the majority of the large plantation workforce, any contact with the former colonial population was no longer regulated by the strict slavery legislation based on racial discrimination. This lead to “new citizens becoming small landowners of their huts on the outskirts of the colony’s towns” . In Saint-Denis, the island’s main city, former slaves built their huts in places known as ‘les Lantaniés’, ‘Camp-Ozoux’, ‘Camp Calixte’, ‘Patate à Durand’ and ‘le Butor. The same trend was observed in rural areas, where Blacks built their huts on the outskirts of large plantations or on the edge of gullies, living on small and often uncultivated plots of land. This similarity of social station allowed Moring to increase in notoriety and was even practised by certain coloured Creoles or poor white folk, but this category remained limited compared to that of the island’s Afro-Malagasy descendants. The new social order resulting from the abolition of slavery therefore contributed to the spread of Moring across other classes of colonial society. Until the First World War, Moring combats remained the main leisure activity of the poor Creole population of Reunion Island, perfectly respecting a code and set of rules accepted by all participants. It would be clumsy to say that Moring was like a dance, simply because combats were accompanied by beating drums, whether real (roulèr) or makeshift (tin cans) as used up in the hills of Trois-Bassins or Ligne Paradis . The violence involved and strict combat rules immediately correct this false image of Moring. It was performed all year round, but especially during ceremonial occasions, 20th December or Indian festivals. Combats would be organised in the homes of keen Moring enthusiasts, or sometimes shopkeepers would arrange them, giving them the chance to sell more rum, the Moring fighter’s favourite drink. Failing that, they would take place in small arenas known as a ‘rond’, a specific fighting ring marked out on a dirt track where Moring enthusiasts would regularly go.

A Moring combat is spectacular both in its theatrical staging and in its technical sequences. Spectators gathered around a ring (three metres in diameter) and eagerly awaited the start of a fight that always began with a ritual of provocation. This part of Moring was in fact a high point around which the whole combat revolved . A drummer, usually a former Moring fighter, started the combat by playing his instrument . As a prologue to the fight, the beat started off slow and dull, inviting opponents to come forward and enter the ring. The role of the drummer (also the referee) was crucial because the rhythm and intensity of the fighting depended on hims . Joseph Pitou, born in 1910 in Saint-Benoît, insisted on the drummer’s importance: “the drum sets the rhythm of the combat. The opponents move around to the rhythm, their guards up. He uses a different rhythm for the battle. Fighters use their feet and heels but not their fists” . According to Joseph Pitou, the drummer could even influence the fight if he wanted to by simply changing the rhythm to reduce or increase the intensity of the blows. Similarly, he could prevent the fight from starting if there was a mismatch of strength or even stop it if he felt that the rules were being broken and that a fighter could be killed.

After a few minutes of drumming, an experienced Moring fighter, encouraged by the audience, the atmosphere within the arena and a few glasses of rum, would finally enter the ring. After that he would make his way around the ring, announcing his age or the ages of those he agreed to fight. Unlike the martial arts of today, Moring never had weight categories and fighters would rate their own chances of victory depending on the opponent who threw down the gauntlet. When an opponent accepted his challenge, he would join him in the ring and would also start to move around in circles.

After the challenge, the second phase of the Moring involved a faster rhythm with shorter, sharper drumbeats. Initially they would goad each other with intimidating gestures, while at the same time sizing each other up in order to find the best way to attack, and then they would attack, locking horns in a merciless and violent struggle. The speed of the drumbeat would depend on the age of those fighting: if they were very young, the rhythm was fast, if they were older, the sound would be slower and duller.

Generally speaking, the fighters had toned physiques combining flexibility, strength and agility. Their movements and acrobatic dodges were admired by the watching enthusiasts. Fighters moved smoothly, without sudden movements and could, at any moment, pounce on their opponents like wild animals on their prey. Accepted moves were known to all and the crowd watched closely to see how things would unfold, taking sides if the combat was unfair. Any irregularity would lead to the fight being stopped and the crowd would intervene to separate the fighters who did not accept the rules. For example, if a fighter used his fists, a sound would ring out to end the fight. In fact, this rarely happened, as fighters would respect the rules because their reputation was at stake. Furthermore, the art of Moring was sacred and no real fighter would have stooped so low to use his fighting skills to take revenge outside of the ring. Moring was therefore not a fight and opponents respected each other both before and after the fight, regardless of the outcome. As Georges Fourcade put it so well, Moring ‘was like a game and a rite with its very own spirit’.

During a combat the participants remained loyal and respected the rules. A man was not hit on the ground or wounded if he no longer wanted to continue the fight. In the novel by Marius and Ary Leblond, Ulysse Cafre fights according to the traditional roles of Moring. The author also points out that “these sons of blacks, either brought up by their parents or raised close to the masters, fought not as savages, but as comrades. Even at the height of the battle, they kept their manners” . A fight was not limited in time and could last as long as the opponents had the strength to fight. They could even stop by mutual agreement, drink a glass of rum and start the fight again after resting. Before fighting, some fighters would pay a visit to a sorcerer who would sometimes cast a spell on their opponent who was reputed to be invincible, thanks to a different sorcerer. In such a case, the fight was often deadly because the combatants, convinced of their strength, would fight to the very end. Eye witness accounts tell of the feats of prestigious Moring fighters who left their mark on the island’s history. The names of noted individuals include ‘Laurent le diable’, ‘Coco l’enfer’, ‘Henri la flèche’, ‘Cadine’, ‘Chou-fleur’, and ‘La Marc Café’ often reappear in stories. This visual nicknames impressed the audience, who had a real admiration for the stars of Moring.

In recent Moring combats, kicks are essential techniques and using the fists is forbidden. At the beginning of the century, punches were sometimes tolerated. In Leblond’s work, Ulysse Cafre kills his opponent Bébé using his fists . Kicking is a vital part of the art of Moring . Dressed in ‘Moorish’ trousers, baggy canvas breeches reaching down to the knees, performers would generally fight bare-chested. Former Moring combatants remember the different techniques they used: there was the simple or double ‘bourrante’ (a flying forwards kick with the heel moving in a straight line), the ‘zirondelle talon’ (swallow’s heel), the ‘talon malgas’ (Malagasy heel), the ‘coup de pied zizo’, (the scissor kick) the ‘kas kou san tous’ (also known as just ‘san tous’), the ‘talon la roue’, (the wheel-heel) and the ‘coup de tête cinq mètres’ (the five metre headbutt) were known to every Moring enthusiast. All these techniques were learnt through experience by Moring fighters who jealously guarded their secret, only sharing them with the very best.

A Moring combat was a real moment of celebration for audiences . The drumbeat made them feel part of the fight. As with cock fights that took place in small arenas, the crowd buzzed to the percussion and the atmosphere in the ring was always tense. The crowd encouraged, challenged and even criticised the fighters. Each town had its own Moring rings, which were most often in poor, African-dominated neighbourhoods all over the island: ‘Coeur-saignant’ in Le Port, ‘Barrage’ in La Saline, ‘Butor’, ‘Petite-Ile’, ‘Lantaniés’ in Saint-Denis, the Rivière de l’Est district in Sainte-Rose, ‘La Mare’ in Sainte-Marie, ‘Trois−Mares’ in Le Tampon, and ‘Ligne Paradis’ in Saint-Pierre. Maurice Poleya, a former villager of Le Brûlé (since passed away), retold his passionate memories of Moring in the village: “Le Brûlé was one of the leading places for Moring. We used to meet on a grassy field and perform Moring, beating the rhythm out on a box used as a drum. Depending on the day, we would either practise for fun or to really fight. Often blood was spilled, but when things became too rough, fighters were separated” . Flavien Lacoudray, born in 1915, confirms this version: “my father, my brother-in-law and some old men from the hills were seriously into Moring. Anyone could take part. Moring was done anywhere, even on the side of the road. We weren’t paid to fight. When the fight was over, we bought a litre of rum and everyone drank a shot”. Moring fights therefore had a real meaning for those participating. This sacred ritual to the beat of the muffled sounds of the tam-tam drum gave Moring a magical character that enthralled the Creole population. In their novel Ulysse Cafre, Marius and Ary Leblond portray Moring heroes fighting each other, bewitched by the almost supernatural passion of the combat. Ulysse Cafre notably forces his opponent Bébé to enter the ring, despite the latter’s reluctance. When asked by Bébé why he was provoking him, Ulysse Cafre simply answers with a single repeated word, ‘Moreng’. And it is this rhythmic sound of the drum, a haunting and haunting binary beat, which draws Bébé into a violent fight that would cost him his life. With its magical qualities, Moring thus played an important role in the life of Creoles of colour. As a form of therapy, it allowed people to vent their everyday frustrations that built up each week. It freed the spirit from a body suffering from social problems. In each fight, combatants would reconnect with their ancestors and their warrior culture. By entering the ring, fighters were facing themselves as well as their opponent, an indispensable partner to exorcise the violence of everyday life. As in traditional African societies, the unconscious aim of the combat was, as in traditional African societies, to use controlled and ritualised violence to restore social order that had been disrupted for people who had been deprived of their roots . Moring was a way of offloading and casting aside the many burdens of this traumatic and rigid social order.

Beyond its sporting nature, the art of Moring, thanks to its magical rituals, has strongly impregnated the cultural history of Reunion Island. As part of night-time culture, Afro-Malagasy culture inherited from slavery, and this occult culture (denigrated by mainstream culture) has marked the popular traditions of Reunion Island for nearly two centuries. A martial art exclusively practised by Blacks in the early days of colonisation, it spread to other strata of the colonial population and became a real tradition of the lower classes in the 20th century. Its decline and then disappearance in the 1950s and 1960s still remains an enigma. The violence of the fighting is not enough to explain its disappearance from Reunion’s cultural heritage. For two whole centuries, the violent Moring combats had attracted crowds and aroused an almost magical fascination on those who watched or took part. So why did Moring suddenly disappear? Why do the elders still speak of this practice with fear and passion without passing it on to the younger generations?

The rapid evolution of Réunionese society and the technical and social changes resulting from departmentalisation seem to have played a part in its disappearance. Rejected because it was too reminiscent of the period of slavery and colonisation, it was replaced by other leisure activities which did not have the same cultural significance. The history of Moring remains to be written and there is no doubt that this sensitivity to the past will one day be able to find its rightful place in the cultural spectrum of Creole society.