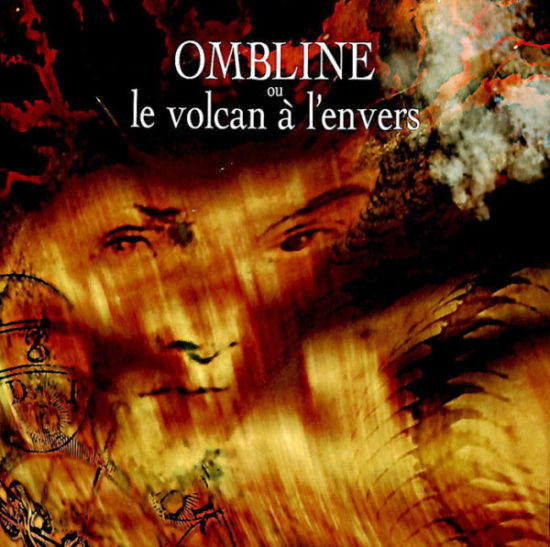

In 1983, Boris Gamaleya published Le Volcan à l’envers ou Madame Desbassyns, le Diable et le Bondieu (The reversed volcano or Mme Desbassyns, the Devil and God) (ASPRED, Saint-Leu, 1983). This play was both a continuation and a turning point in the author’s writing.

A continuation in that the dramatic and theatrical potential of his two preceding collections of poems Vali pour une reine morte (Vali for a dead queen) (REI, Saint-André, 1973) and La Mer et la Mémoire – Les Langues du Magma (The Sea and Memory – The Tongues of Magma) (Imprimerie AGM, Saint-Denis, 1978), are duly reiterated and made systematic in a theatrical work.

Actually, the dialogues in the first works already announced a dramatic rhythm, at times through highly lyrical love duos (Rahariane and Cimendef, Anissia and Sangolo), at others through highly agonising conflicts between the fugitive slaves (Cimendef, Anchain) and the slave hunters (Mussard, Bronchard).

In addition, there was a theatrical structure deeply underlying the two texts, creating an alliance between ritual and initiation – in Vali pour une reine morte, a long litany of trials leads to a fall, with the characters now needing to pick themselves up: “I’m falling / the burnt memory of the milk of your euphorbia”, or which configured the contemporary struggles inspired by a close knowledge of past struggles. In the second collection, a double work, everything is focused on initially creating the image of “a man remembering his devastated possibilities”, “who falls and rises up/among the constant cries/of history”, then later creating a dynamics for today’s struggles by giving homage to the militants fallen under the beatings of the thugs (“I just need to pronounce a name François Coupou/ I just need to pronounce a name Éliard Laude / I just need to pronounce a name Rico Carpaye”), and above all through projection, through words that have become “ birds of a new practice”, of “an undisputable scream”, “ history is life gradually triumphing/and not simply our dead// the struggle continues”.

A turning point in that from now on, like the sea which provides him with a precious model, since for him the sea is “synthesis going beyond man”, Boris Gamaleya is determined to create in his work complex dialectical structures aimed at establishing “a strange synthesis”, deliberately going beyond all the dead ends of history created by all binary oppositions (between genders, classes, nations etc.) impose on us all.

In this respect, the preface by Gilbert Aubry is extremely helpful for an understanding of these new challenges, notably when he draws a parallel between Boris Gamaleya and Ernst Bloch and his “principle of hope”: “The spiritual rises to the surface in the materialistic field of praxis. Not as a chimera, but as cultural dynamics coming to the fore, attracting and captivating while remaining, however, inaccessible and fleeting. This is “the Principle of Hope”, somewhat like the image of the statue bewitching the sculptor and drawing him forward as he sculpts. This is “what is before us, within which both the core of man and that of Nature, in a utopian manner achieves – or does not succeed in achieving – their final fulfilment.” (E. Bloch)

In fact, Boris Gamaleya himself wrote these sentences in the foreword to his book: “This is the Reunionese book thanks to which you can witness God during your lifetime, as well as hell and purgatory, without needing to die.” (after a presentation of liber secretus, cf E. Bloch, Le Principe Espérance).

With Le Volcan à l’envers ou Madame Desbassyns, le Diable et le Bondieu, through his future work Gamaleya sets himself up as a Reunionese Dante writing a truly Creole Divine Comedy, based on “the strange synthesis”, always evolving in the direction of his potential “final fulfilment”, between Marxist thought and Christian spirituality, but also between the child and the maturing adult: « Adieu my origins/ I have reinvented everything”, “let me give myself up to you/ inaccessible/ rebuild the island within me// MY CHILDHOOD IS CONTINUING.”

In 1998, the book was reissued with l’Oratorio 1998 (Océan Éditions, 1998), added on and which is a continuation of it, since it crystallises and purifies it: “through the Way of the open crack/ on both sides/ from realm to realm/ pahoé ohé o/ nothing is as it was/ nothing but this cross”. The text of the oratorio is the text that Boris Gamaleya was to transmit to Ahmed Essyad, as a commission by the French State for the celebrations of the 150th anniversary of the abolition of slavery.

Between the two dates, four important books were published: Le Fanjan des Pensées – Zanaar parmi les coqs (Imprimerie AGM, Saint-Denis, 1987), in which Gamaleya deliberately committed himself to a spiritual turning point, inspired by history’s great mystics, from Jean-Joseph Rabearivelo, as well as Indian Ocean ancestral traditions; Piton la nuit (Éditions du tramail/ILA, Saint-Denis, 1992), in which the sacred mountain and the dark night symbolise this high ambition, in the search for “coincidences of all that is open”; Lady Sterne au Grand Sud (Azalées Éditions, Saint-Denis, 1995), where love for a woman, love of the island, love of freedom, love of music, love of poetry and love of the spirit soaring skyward form a single brilliant whole; L’Île du Tsarévitch (Azalées Éditions, Saint-André, 1997), roème, or roman-poème (novel-poem), where the transfigured narrative of the life of the father makes it possible for Boris Gamaleya to mingle with extraordinary dexterity all the topics previously treated, as though bringing them together in a formidable display of light marks not only the end of the cycle, but also re-launches the work along new highly promising pathways.

It is in the light of this creative development that the specific and essential characteristics of l’Oratorio 1998 are to be understood.

1998, 150th anniversary of the abolition of slavery in Reunion. Commissioned by the French state, it was the opportunity to create an encounter between two strong personalities, the Reunionese Boris Gamaleya and the Moroccan Ahmed Essyad. The former had the role of writing the lyrics of an oratorio, while the latter was to write the score.

Catherine Trautmann, minister of culture, wrote: “The commission was entrusted to two artists, Ahmed Essyad and Boris Gamaleya, who, each in their own way and in their works in general, celebrate the diversity of cultures and the liberty of the individual.” She added, “I am particularly delighted with the encounter between these two talents: Ahmed Essyad, the composer, an uncontested vehicle of the best oral tradition at the heart of the most written music… and Boris Gamaleya, poet, pioneer and militant for a Creole culture open to universal values and whose play Le volcan à l’envers has become a symbol and a reference in Reunion.”

So that their collaboration would be as fruitful as possible, Ahmed Essyad came to visit the island. Their encounter was moving and the work sessions smooth, despite a few misunderstandings that the two men made efforts to overcome. One stumbling block remained: Boris Gamaleya would have liked their common work to echo more clearly the music of former slaves; Ahmed Essyad remained adamant: his music with its demanding and specific style, founded on intricate and sensitive transfigurations with their distinctive characteristics born out of musical traditions, not only of his country but of the entire world, was not easily adapted to the verbal “quotations” of the maloyas, inserted into the body of the work by collage or by more subtle processes of integration. Boris Gamaleya, a fervent lover of music, would have preferred a work close to that of Luciano Berio in his Folksongs, a post-modern project leading to a musical patchwork capable of producing a ‘strange synthesis’. Ahmed Essyad, fascinated by the magmatic and metamorphic beauty of the language of Gamaleya, refused to give in: resolutely modern, his music will also be an incandescent fusion, with elements drawn from traditional music mingling together, without always being recognisable as such. The discussion between the two creators were passionate, going as far as to create an exemplary controversy, of which, unfortunately, only a few extracts or traces remain. The poet mentioned it in passing, while the composer chose to remain silent.

In fact, a few years previously (1991-1994), Essyad had composed L’exercice de l’Amour, an opera “of light” based on a text by Bernard Noël, with whom he collaborated again very soon afterwards for another opera, Héloïse et Abélard (2000). These are works of a spiritual character, in which his inclination towards Sufism combines very successfully with the negative theology of the western Mediaeval tradition, revisited with passion by Bernard Noël. Concerning the elevation of the soul, Essyad and Gamaleya recognise that they were inhabited by similar aspirations. We can mention that on other occasions, the composer pronounced the following words, that could, in fact, be attributed to the poet: “a cultural synthesis which did not place human thought at the forefront, not enrich the present with a new experience, would not permit double astonishment, continent to continent, that territory where man can finally lose himself.” From continent to continent, or from island to island… Gamaleya understood that his text was to be the quintessence of the work which finally gave depth to the direction of his writing, orienting it towards “the euphoric services of transcendence”, as he says in the Foreword to the Oratorio 1998.

Thus is this book, entitled Ombline ou Le volcan à l’envers, an abridged, even a transfigured version? Based on the “comings and goings of an infinite imaginary space, implicit and continuous maroonage towards a future based neither on neither truth nor lies”, it is designed to resolve “differences”, initially between fugitive slaves and slave owners, “in a festive participation of synthesis, the insular work at last open onto the universal.”

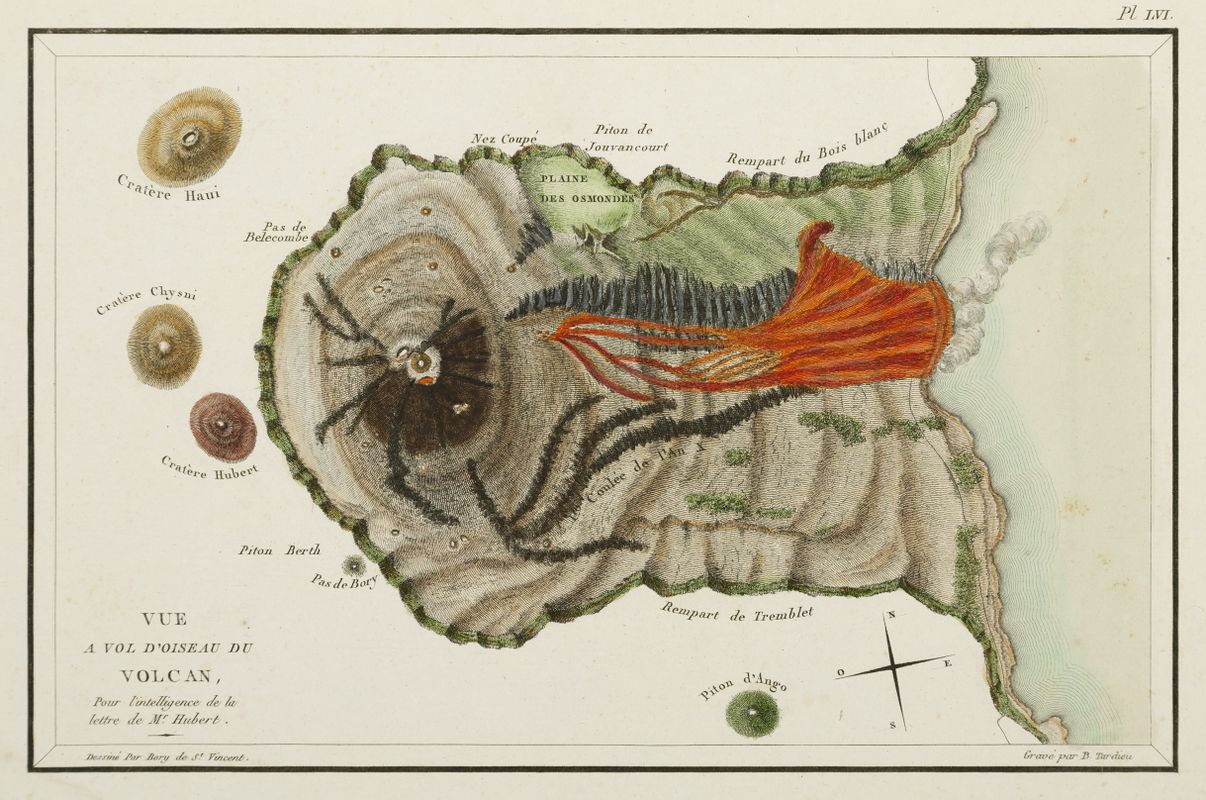

Pierre Gervasoni gives us a clear summary: the narrative, “set on the volcano of la Fournaise, where and number of fugitive slaves have taken refuge, is organised around four sections of unequal length. The first involves several characters (Simangavole, Matouté, Sankoutou) linked to the beliefs of maroon kingdoms. The second is linked, in an elliptical manner, to the destiny of two lovers (Sarah and Sinacane) in this burning space beyond. The third brings in Ombline Desbassyns, pious but pitiless slave-owner, invited to take on more liberal ideas in the world of the dead than she did in that of the living. The fourth finally delights in the expected conversion of the aristocrat and praises the fruit of her union with Sankoutou, taking place on a volcano that has now become a paradise.”

Each section opens with a monologue, the first section with the following words: “Finally, we can be/all this.” This claim to achieve a plurality of being is based on an evocation of la Plaine des Sables, close to the Piton de la Fournaise volcano, a sort of small desert space, and a place propitious to asceticism, necessarily predisposed to true access to the euphoria of going beyond oneself: “ the freezing wind”, followed by its wake of “ voices coming out of the depths”, creates a structure whispering with resonances and echoes, enabling propagation “from flame to flame” and “from end to end”, of a vibration unifying everything along its way: “kolokolok echoes – of the scarlet magma”, “lapping sounds inside the cribs of the conch shells”, “seeds of flutes enchanted by trickles of water”.

The second section thus evokes the breath of everything with everything, reflected in the exemplary couple of the fugitive slaves Sarah and Sinacane. Gamaleya transforms a volcanological term borrowed from the Hawaiian language (pahoehoe : “ river of satin”), referring to an extremely fluid lava, like that flowing out of the volcano in Reunion, an onomatopoeia expressing both the sharp whistling of the basalt magna tumbling down the slopes, as well as a kind of appeal to break down barriers: “Pahoé oé o Pahoé oé é”… And Sarah is in ecstasy as she witnesses the arrival of a general harmony: “I can hear an orchestra carrying skywards all the gold of the night.”

At the opening of the third section, the most crucial and therefore the most developed, the volcano is defined by the narrator as being “a crater of intoxication”, and by the chorus as “the conch shell announcing the Other Reign”! After she has died, Ombline arrives at the volcano, kingdom of escaped slaves, where she “witnesses [her] strange negations”. Her initial reaction is in keeping with her social class and her history: “Musketeers come to me! … Come and annihilate this place of anarchy!” However, Sankoutou finds “a better role for her to play” : “Either you come to celebrate with us or you go back to your putrid cot…” The aim here is to take leave of historical determinism, full of noise, anger and resentment, to achieve a “joyful treasure” born out of the “syntheses/ pure thoughts on everything”. Sankoutou argues and finally convinces Ombline: “ There is no history other than that of the word that calls you. Between death and your altered image, the choice is simple for a soul become free for eternity. No tyrannical future now comes to threaten her. They can now enjoy new beginnings!” The breath of all with all now takes its life from the “magmas of all breaths!” and Ombline lets go (“divest me of everything”), crying out: “Earth above! Heaven below!” The synthesis takes place and the volcano is overturned.

The epilogue which makes up the fourth and a very short section celebrates “a harvest of epiphanies”, now possible since the “cyclonic swarms” of history have consumed “their violence” and we have now abandoned the “chaos of falsity”, to walk along the path leading to “the chasm, open on either side…”