Whether for the national commemoration of the slave trade, slavery and their abolition since 2006, or for the centenary period of the First World War between 2014 and 2018, the National Education has also found itself caught up in this ‘commemorative’ movement which Antoine Prost already spoke of back in 1996 . The everyday life of every teacher has therefore been influenced by this renewed social, political and academic context for more than thirty years.

All studying at school takes place within a social sphere which is characterised by a profound need for identity markers. This leads to the expression of a number of historical events with narratives which seek to either move or affront. These memories are carried individually, handed down through families or associations, and may give rise to private or public commemorations (a term originally linked to the religious sphere). Even when forbidden or suppressed, these tributes always end up reappearing in a public arena. This explains how, from 1849, the celebration of the abolition of slavery in Reunion Island was restricted to private gatherings, as the island’s authorities saw this as potentially harmful, demonstrating a clear political will to forbid such festivities. The 20th of December wasn’t officially celebrated until 1983, by François Mitterrand’s government.

From the end of the 1980s, following the process of decentralisation which boosted regional cultural policies, increasing numbers of associations and artists appeared on the scene, seeking to affirm their identity around the theme of slavery. The consequential interpretation of history was an attempt to reconstruct a binary world divided between masters and slaves, whites and blacks, powerful and weak, often used to explain contemporary discrimination or social inequalities. However, the historical reality is more complex. For example, we know that 80% of slave owners on Bourbon Island lived in poverty. This in no way detracts from the brutality and inhumanity of slavery , but does imply a more nuanced proximity between masters and their slaves than that of the often imagined stereotypical rich colonist from works such as Gone with the Wind. This dualistic vision also overlooks the existence of the group known as ‘Freedmen of Colour”, freed slaves or their descendants, among whom were landowners who themselves owned slaves. Although the 1674 decree from The Hague forbade any “Frenchmen from marrying Negro women” and any “blacks from marrying whites” on the island, there were in fact too few women for the settlers to have any real choice. The example of Marie Case, one of the first three Malagasy women on the island, is representative of this historical complexity. First married to a Malagasy man ‘in the service’ of the French East Indies Company, she became a widow and then got married to Michel Frémont from Normandy after 1689. When he died, she became the owner of 14 slaves. On the other hand, archives show that there were white slaves in the society of Bourbon Island, even though they were a real minority. In a post-mortem inventory carried out in 1840 in Sainte-Suzanne, Prosper Eve noted many descriptions of slaves that were the result of crossbreeding : “Aristide, 21 years old, Creole, white, black and curly hair, height 1.70m”, “Arnold, child of Mélanie, 2 years old, Creole, white, blond hair”.

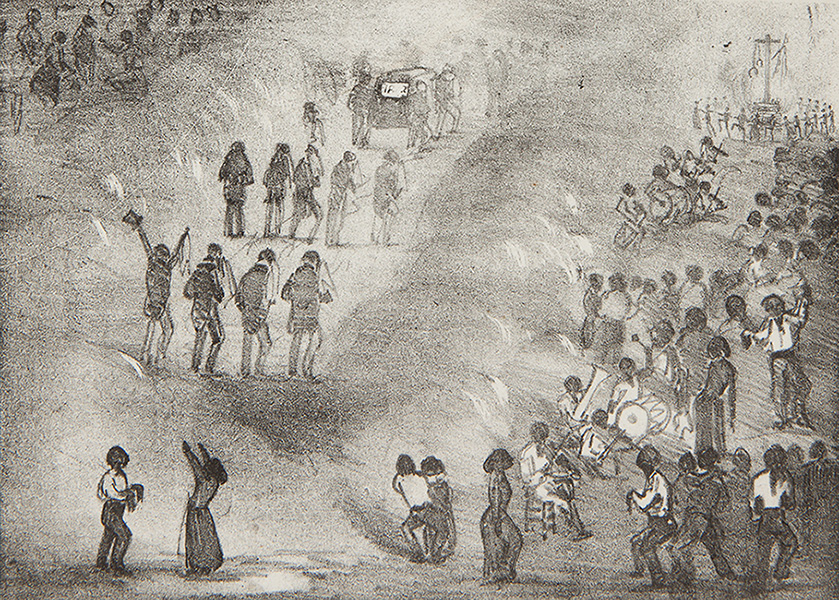

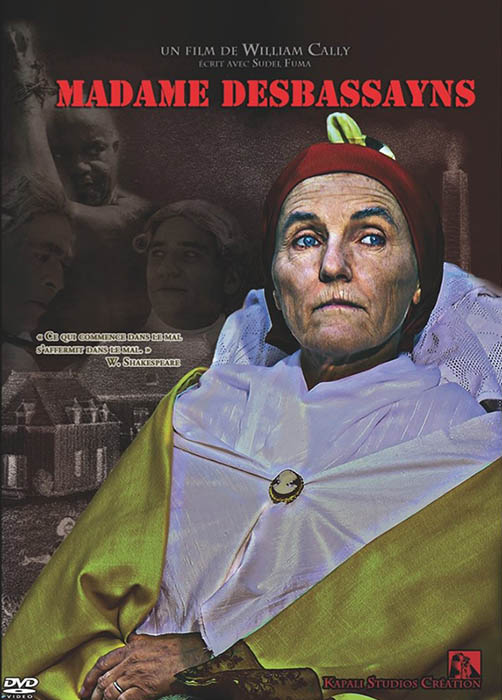

Especially for younger pupils, learning requires simplification, but the difficulty for the teacher is also to fight against preconceived ideas, especially when they have been transmitted through docu-dramas, a television genre driven by society’s demand for historical portrayals. This was the case with ‘Elie ou les forges de la liberté ’ by William Cally, co-written with the historian Sudel Fuma on the occasion of the bicentenary of the slave revolt in Saint-Leu. For example, the scene where a plantation foreman brutally assaults slaves who are already working, without any reason, conveys the same image of gratuitous violence that can also be seen in another 2015 docu-fiction by the same authors, a portrayal of Madame Desbassayns.

This caricatures a violence that was inherent to the slavery system and that could take many other forms, forgetting that it was not in the owner’s interest to work his slaves to death. However, this is the recurrent image of pupil’s drawings on the subject. Furthermore, the slaves are all dressed in immaculate white clothes for work in the fields, Elie even wearing a shirt and a waistcoat, while most often they were dressed in simple blue canvas trousers. When transporting water from Ravine du Trou, several miles away from the houses, barrels were used, but in the film we see slaves carrying buckets. Another historically problematic example is Delacroix’s painting of the 1830 revolution, which appears in both films to evoke the French Revolution of 1789. Finally, there are doubts about the film’s portrayal as Elie as a hero, as studies of judicial sources show that everything points to the commander Gilles as the initiator of the conspiracy. This does not detract from the importance of Elie’s role in the movement, but the problem is that this revolt of the slaves in Saint-Leu is portrayed as the revolt of Elie himself. This would suggest that Reunion had indeed found its ‘black Spartacus’, never mentioned in memorial speeches, unlike the embodiment of the resistance to slavery which might probably have existed in the West Indies. Other historical errors can also lead spectators, including students, to historical misunderstandings. For example, the film about Madame Desbassayns shows slaves toiling sweat and blood in sugar cane fields, but the scene is totally anachronistic because, even though plantation trials were indeed carried out by Laisné de Beaulieu in 1785, sugar cane was not common until much later . If this need for a historical portrayal gives rise to films produced by memorial associations, a film-maker and a historian committed to the popularisation and dissemination of knowledge, it is clear that such teaching aids require accompaniment to ensure pupils maintain a critical eye, and are able to distance themselves from portrayals that are sometimes clearly guided by identity claims.

This desire to pay tribute is also widespread among dramatists and artists. First performed by the Vollard theatre group on 12th December 1981 at the Grand Marché theatre in Saint-Denis, Emmanuel Genvrin’s play ‘Marie Dessembre’ had a major impact, and justifiably so. Another example are the works by sculptor Marco Ah-Kiem, also on the theme of slavery. Whether the statue of Madame Desbassayns (today found in the gardens of the Villèle Museum in Saint-Paul), or that of the slave Mario (now next to the Black Madonna in Sainte-Marie), his works play a role in commemorating the island’s history . Based on the legend of the slave Mario , the statue commissioned by the Racine et basalte association for the 150th anniversary in 1998 has even become an object of worship, almost like an intermediary between the people and the Virgin Mary.

Entitled ‘The Water Bearer’ this statue also bears witness to the different messages these memorials can convey. Through this sculpture, Marco Ah-Kiem paid homage to his mother who would have to fetch water using a bucket every day, and the work was purchased by the St Denis city council who wanted this message to resonate for local citizens. One day, someone talking to the sculptor told him that, though they found the sculpture magnificent, they couldn’t imagine that it was a reference to the period of slavery! The sculptor assured them they were right, as this represented his mother’s daily tasks… In any case, a visit to Marco Ah-Kiem’s collection of sculptures demonstrates the impact that slavery can have on artists from Reunion Island . Music is another artistic domain which teachers can also use in class – Davy Sicard’s lyrics can be an ideal teaching source. One example is ‘Marianne’, a song in which the singer emphasises his pride in being influenced by the memory of French republican figurehead Marianne and by that of the rebellious slave Marianne . The difficulty lies in providing a critical approach to history instead of using forms of artistic expression to unwittingly pass on preconceived ideas about slavery.

The Education system is also part of a political domain in which the commemoration of slavery has become a duty. As representatives of the republic, teachers are called upon to participate in this duty, the objective being to create a democratic society based on the principles of inclusion and tolerance. State action was affirmed in 2001 with the formal recognition of the slave trade and slavery by Europeans as a crime against humanity. The first direct consequence of this law was the appointment of the Committee for the Remembrance of Slavery (CPME) in 2004, given the task of proposing measures to ensure that this subject is given its rightful place in national history.

The Committee’s work represented a turning point for education, as shown by the rewritten school curricula back in 2010. As a clear consequence of this progress, teachers in overseas France have had to deal with two dates for the commemoration of the abolition of slavery since 2006. In Reunion Island, the 20th December was already the subject of numerous educational activities, but an academic competition entitled ‘Slave Trade, Slavery and Abolition’ was introduced in 2011, and in 2016 became part of a national competition called ‘The Flame of Equality’ an initiative led by the National Committee for the Memory and History of Slavery (CNMHE), which took over from the CPME . Along with 10th May, these two dates in fact serve to provide even greater teaching resources: one date belongs to the history of Reunion Island, whereas the date in May enables us to learn more about other regions which were also marked by colonial slavery. Those in the West Indies may not know much about the history of slavery in the Indian Ocean, but do the Reunionese know the story of Cyrille Bissette or Louis Delgrès?

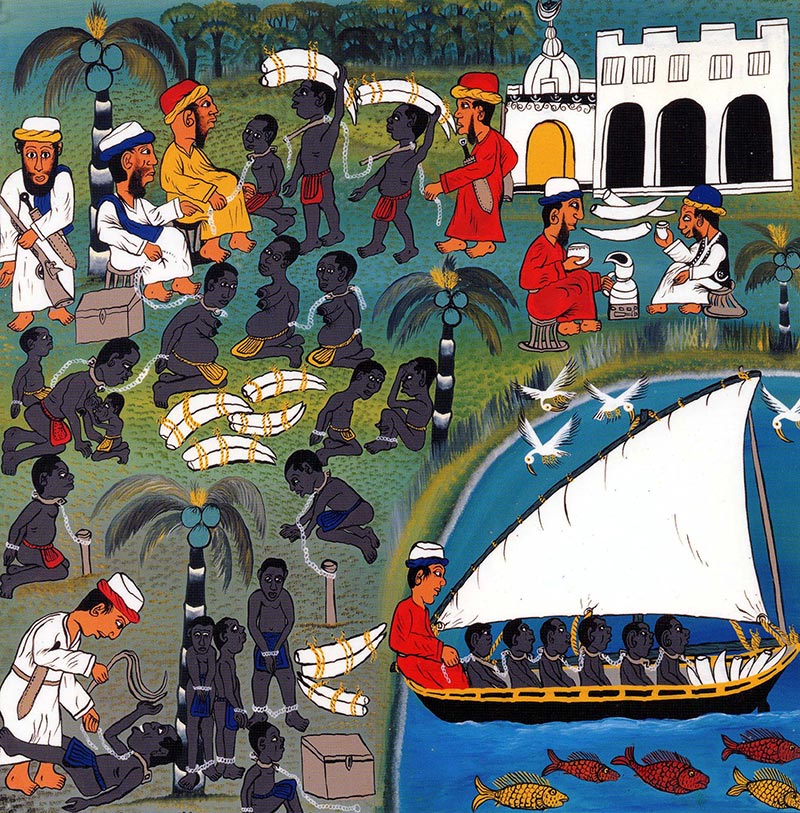

However, despite the political choice to consolidate this particular subject in schools across France, slavery in the Indian Ocean is given very little coverage. In fact, in editions from 2011, all secondary school textbooks devote about ten pages to the general theme, but none of them include any documents related to the Indian Ocean. Thus, all French pupils will understand that slavery plays an important part in the history of France, discovering documents related to the Caribbean region, and young people from the West Indies and French Guiana will be able to identify with this history. However, pupils of Reunion Island will find no mention of their island, albeit merely a map of the slave trade with a few arrows pointing towards the Indian Ocean… When dealing with this subject, Reunionese Member of Parliament Huguette Bello questioned the Minister of Education on 30th May, 2011 . It would hardly have been difficult to refer to a ‘transoceanic’ slave trade instead of ‘transatlantic’, but no doubt this considerable modification would be rendered difficult to implement, simply due to the weight of the Caribbean’s historical role in the minds of people across France.

It was in Guadeloupe that the French government decided to open a Caribbean Commemorative Centre for the Slave Trade and Slavery in May 2015. Covering slavery in its entirety, from Antiquity to the present day, the ACTe Memorial highlights the resistance to slavery and the route of slaves, presented in a way that attracts the general public in which “emotion takes priority over history” . It also aims to be a centre of contemporary cultural and artistic expression. Although it seems necessary to set up dynamic research centres on the subject in each overseas territory, it is clear that, unlike in England, France has not chosen to create a museum and research on the scale of what can be found in Liverpool, for example .

As well as the government itself, political parties also play a role in this debate. In Reunion Island, the recognition of slavery has been highlighted since 1945, and even more so by the communist party since 1959. Seeking to block the populist democratic autonomy advocated by the PCR (Communist Party of Reunion), their political opponents would avoid even raising the subject. The introduction of the 10th May celebrations in France in 2006 stirred certain controversy linked to this question of identity. For example, on 10th May 2014, the National Front mayor of Villers-Cotterêts refused to organise any official event, denouncing a streak of ‘permanent self-blame’. While some thought that the subject didn’t get sufficient attention in the 1960s, fifty years later there was those who clearly thought that we were talking about it too much… This will to prevent the commemoration of the abolition of slavery to develop comes from a period during which the republic had chosen to build up a nation by erasing the darkest chapters of its own history, thereby stifling certain memories. Implemented from the 1980s, decentralisation (and the ensuing cultural proliferation) has managed to break from this attitude, but at the same time has led to a rise in the number of supposed victim claims that have fuelled the fires of controversy about national identity .

On an international level, the subject was taken up by UNESCO who launched the ‘Slave Route Project: Resistance, Liberty, Heritage’ project in Ouidah (Benin) in 1994. Dealing with a variety of historical places, this work sometimes leans towards a style which is more akin to mythology than history, as is the case for the House of Slaves in Gorée . However, it must be acknowledged that it is also thanks to such examples that intercultural dialogues can be established and history can regain its full place. UNESCO also supported Reunion Island when Maloya music was classified as intangible heritage of humanity in 2009. Politically backed by the regional council of Reunion and its then communist president Paul Vergès, this recognition came about thanks to the work done by Reunionese academic Sudel Fuma, director of the UNESCO chair on slavery and the slave trade in the Indian Ocean. From 2004 onwards, he had initiated work on examining the slave route in the Indian Ocean, the aim of which, according to him, was to develop “a therapeutic memory serving a Creole identity in the Indian Ocean” . For him, this commemoration represented an intermediary making it possible to rely on historical reference points in order to create a political project based on the notion of identity. In this way, he used history to reach an objective: the recognition of the Reunionese people.

History belongs to the field of human sciences. With this in mind, it is not only a scientific practice which follows a method of critical analysis, but also a social practice within any given society in which paradigms evolve. Nationally, the question of slavery and the slave trade has become part of the debate that divides the historical community between those who, as part of the collective known as Liberté pour l’histoire , (December 2005), believe that laws governing commemoration are in fact a hindrance to historical research and those who, on the contrary, believe that without a strong political will, research conditions will never be sufficient when it comes to examining the ‘darker’ pages of history. These controversies between renowned historians in the media is unlikely to help teachers when planning their lessons.

In Reunion Island, Professor Hubert Gerbeau , who arrived on the island back in 1968, played a decisive role in the development of research on slavery. It was he who trained Sudel Fuma and Prosper Eve, who are the two leading academics to have written on the subject from the 1980s to the first ten years of the 21st century. Controversies have existed, such as those linked to political scientist Françoise Vergès and the project of the Maison des Civilisations et de l’Unité Réunionnaise (MCUR), or with the replacement of Sudel Fuma, who died in 2014, which led to a legal confrontation between local and French academics . Despite this, there are many scientific works linked to the special themed day organised by the AHIOI . New research has also come from other universities, such as Marie-Ange Payet’s literary study on escaped female slaves , the historical work by Bruno Maillard in Paroles d’Esclaves or even by Anne-Laure Dijoux in the field of archaeology, where much still remains to be done .

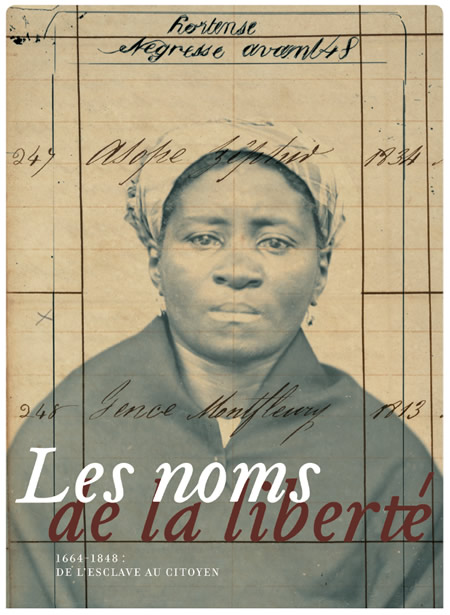

Other work has allowed teachers to widen their pool of resources. For example, studies of old ballot papers led to a remarkable exhibition entitled Les noms de la liberté, displayed in the departmental archives from 2013 to 2015, complete with a full educative manual .

A number of educational projects took place during the 140th and 150th anniversaries of the abolition of slavery in 1988 and 1998 , followed by the publication of local history textbooks from 2001 onwards . There are also exhibitions on the theme presented by the Departmental Library of Reunion Island. This increased number of editorial productions connected to the introduction of the commemorative date of 10th May also led to publications that addressed the issue in relation to the Reunionese context . Finally, the Internet also provides teachers with a variety of resources ranging from research by academics or scholars to specific commemorative projects. Initial teacher training on the subject is key, but continued training courses are even more so, as well as the importance of adapting the official curriculum to the local context.

The teacher’s role is ultimately to accompany their pupils throughout their years at school, bringing them greater understanding of information to which a critical viewpoint must be added, one based more on questioning and doubt than on providing ‘academic’ answers. All of this must be done as part of an investigative and project-based approach, providing pupils with a certain responsibility for their own learning. Unlike university academics, school teachers do not have classes who are destined to become history teachers or historians. The vast majority of these young people will remain influenced by images, preconceived ideas and social and political pressures that often reproduce the same irrational behaviour. History as taught in primary and secondary schools must therefore contribute to forming future citizens capable of understanding that historical reality is much more complex than the information handed down by families, the media or politicians, whether it concerns slavery or other key issues.