The 20th December celebrations were thus witness to what could not be narrated until the 1970s-1980s. On 30th June 1983, following the official recognition of the abolition of slavery and of homage for the victims of slavery, the collective appropriation phase saw the light of day. This past, rising to the surface in the public space 135 years after abolition, gives credit to the hypothesis of a narrative that had been hindered or made impossible, maintaining the oblivion far more effectively than a deliberate policy of amnesia. History and memory are transmitted by men and women, who evolve in ever-changing contexts.

As written by Hubert Gerbeau, the narrative of the official memory of slavery, written by historians who were both “judges and the judged”, transmitted an “aristocratic memory” until the mid-20th century, as established below.

The narrative published by Georges Azéma in 1862, Histoire de l’île Bourbon depuis 1643 jusqu’au 20 décembre 1848 , covers its main elements.

He traces the history of the setting up of the system of slavery, imposed by the French East India Company, holders of the privilege of the slave trade entrusted to them by Louis 14th, similarly to the other colonies. However, the refusal of the first slaves to carry out servile tasks necessitated the organisation of detachments aimed at hunting down the “fugitives” – not maroons – who represented a threat to the existence and the property of “the inhabitants”. There follows the description of the model colony: product of a “fusion” between the “former Blacks” with the Creoles and their “initiation into the morals of the Whites”, living “peacefully in the midst of their slaves” and giving each other “mutual support”. The enrolment of slaves, armed and disciplined, entrusted by Mahé de Labourdonnais with the task of “defending the French flag, now become theirs”, confirmed their devotion. The sweet state of slavery was mobilised to explain the rebellion that occurred in Saint Leu in 1811, caused by the arrival of the British. Since, he declared, the only example of any insurrection occurred in the early days of colonisation.

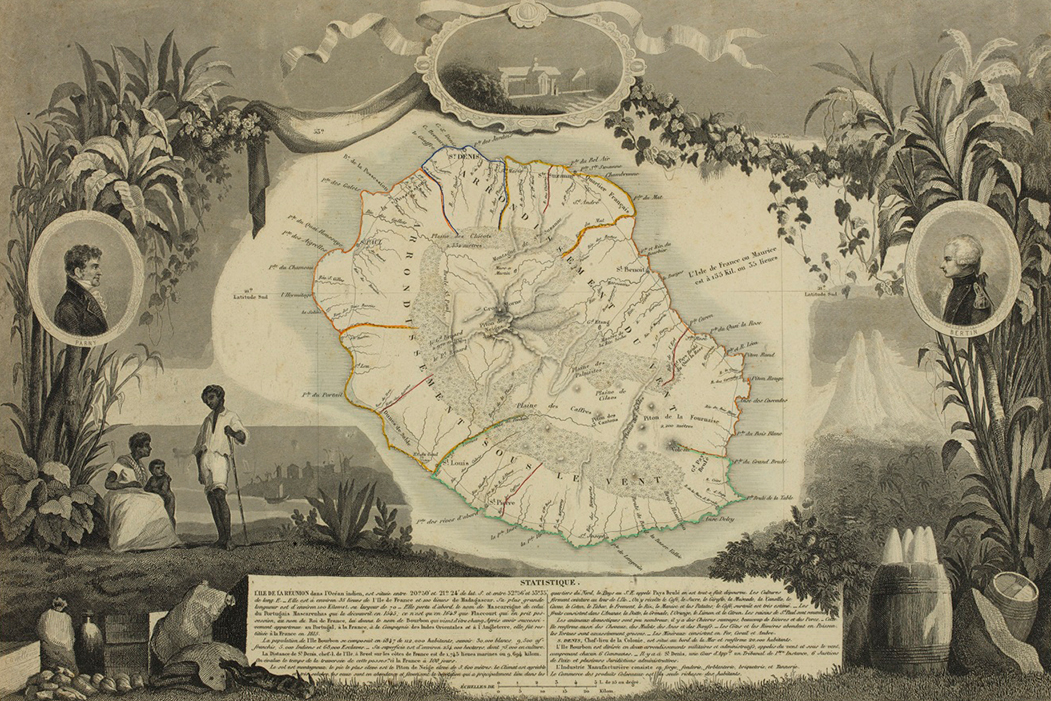

Collection of Reunion departmental archives

Jean-Joseph Patu de Rosemont. [1810]. Drawing.

Collection of Reunion departmental archives

The myth was initially aimed at literate persons and French public opinion and not at the Creole masses without access to the written culture. It was exploited by François de Mahy for the aims of colonial expansion . According to this member of the French parliament, slaves and their descendants becoming Creole and later French, then becoming “sons of the French territory”, possessing equal parts of “the French soul and spirit”, represented a laboratory of the assimilation ideology of the French Republic.

The narrative was made legitimate through the status of the written word; the low level of literacy in the population reduced the audience to a small circle which only expanded under the 3rd Republic. However, the offer of public readership, vector of the written culture, did not produce an alternative narrative on slavery, if we are to judge by the inventories carried out in the 21 public libraries on the island between 1907 and 1917 . Two works treated the topic of slavery: Uncle Tom’s Cabin, present in 5 collections and Paul et Virginie, present in 11 libraries, alongside works on Madagascar. The highly aesthetic presentation of slavery present in these two works was indeed not intended to awaken “the bitter memory of slavery” , but instead reinforced an extremely euphemistic vision of servile labour. As for Robinson Crusoe (found in nine collections) we can wonder if it gave legitimacy to the domination by the master – Robinson – over his servant Friday or whether it served to awake the consciences of the generation of militants during the years of the Popular Front.

Similarly, in the absence of cultural vectors able to recount their family experience, there existed no alternative narrative on slavery, for, unlike the Caribbean, Reunion did not produce an intellectual elite coming from the slaves emancipated in 1848. In fact, in the years between the two wars, while Paulette Narval, with the support of other intellectuals of African origin, was, not without ambiguity, sketching out Black internationalism and while in 1921, René Maran was awarded the prestigious French prix Goncourt literary prize for Batouala, a true novel of negritude, in 1924, Reunion produced the novel, Ulysse, cafre ou l’histoire dorée d’un Noir (Ulysses, African, or the gilded story of a Black) by Marius an Ary Leblond, a perfect illustration of paternalism, avuncular ideology, advocating assimilation.

Has the memory of slavery been lost, however?

In reality, there is not one memory but there are many memories. Private and family memories, existing outside the written word, many and varied like a patchwork quilt and as mobile as the aristocratic memory, were transmitted in parallel from generation to generation. Like the traditional patchwork quilt, made up of scraps of fabric forming a heterogeneous assembly, these memories bear witness and narrate and are the pretext for recalling scraps of personal stories that are also scraps of History, brought back to life on 20th December.

Indeed, abolition was celebrated in private circles , with rituals set up associating Holy Mass, food, recollections of the sufferings of slavery and veneration of the ancestors. A police report issued in 1936 gives an account relating the popular celebration held in Saint Denis by a certain certain Vincent Hibo, as in the preceding years. The authors of l’Encyclopédie de La Réunion published in 1981, confirm the survival of the memory of slavery both in Salazie and along the coast.

As a result, the two memories cohabitate together, the first taking advantage of the domination of the intellectual environment, the other existing underground and being openly expressed as from 1908, according to Prosper Eve.

Le Progrès dated 19 December 1917, quoted by the historian, gives a good summary of the strata of the process of memory according to the generations. The first was that of the “Black of 1848 […] never daring to boast of this extraction, if we may say so, or to declare this starting point of his civil status [the expression having left such an important mark], the disdain for the inferior morality naturally resulting from these origins […] An emancipated Black was inferior to another Black.”

The Second Empire and the start of the 3rd Republic saw the arrival of a second generation, who had witnessed the silence of their elders and their attempt at integration. That of 1908, the third generation, claiming recognition for ‘la fêt caf’ (celebration of Abolition), requested recognition of a slavery still existed.

What was the meaning of the term “slavery”, three generations after abolition? In 1908, for the Journal de l’île de La Réunion : “slavery still exists for the lower classes, […] as hateful as the other (my underlining) weighing down on the young”. For Le Peuple en 1929, l’esclavage, creuset de la société créole, doit avoir pour symbole de la libération et de la conquête de la dignité le 20 décembre. En 1936, dans Le Progrès , slavery and the post-slavery proletariat are “the consequences of the capitalist regime that imposes salaried workers and bosses”, so a symbol of the class struggle.

The revival of memories, consequence of a questioning of the past by those alive, thus bears witness to the fact of slavery becoming invisible, which remains a form of epistemic violence.

Creating a past that is inhabitable and inhabited by all

As has been said, local historians mentioned slavery in their writings. Those of Elie Pajot, Simples Renseignements sur l’Île Bourbon , can be found in public libraries. The account of the 1811 rebellion, admittedly very biased, is mentioned, but the issue of slavery had to become an issue concerning the present before the new generations would appropriate it and gather together the archives making it possible to reconstitute the facts.

Historical accounts would have remained self-pitying and truncated if the historians of the 1970s, blinded by trans-generational suffering, had not operated a shift of focus enabling them to see a slave not as “mobile goods” but as a man or a woman, capable of resistance despite the coercive system. Distance has made it possible to ‘cool down’ the object of study.

The context was favourable to the development of historical research, contributing to give visibility to the system of slavery through artistic expression, including sculpture. Distributed unequally over the territory, the aim of the statues is to project an alternative narrative within the public space, another narrative of the past up till now represented by the great men of Reunion, occupying the center stage. However, while for obvious symbolic considerations certain places have been given highlighted, the topography of these places of memory brings out the conflict between the different memories.

Indeed, the issue of slavery is no longer a taboo, but the temptation to attribute to each of the components of the settlement of Reunion one narrative of the past remains strong: there seems to be a history of slavery as seen by the Whites, in which low-income Creoles play a role and another, that of those who worked under constraint (slaves and indentured labourers).

In fact, in a symbolic manner, the statues erected enhance a narrative of the past for the living. They see in them elements of their genealogy, providing they avoid reproducing a segmented narrative of the past which makes the actors invisible, whatever role they played in the common past, and which excludes them from History.

Since, as was repeated by Hubert Gerbeau, “that slavery which shocked the economies, bodies and consciences, shocks which were at times mortal, irrigated the social edifice as would a storm” , led to a transformation of an anthropological character. The fact of slavery was, indeed, a total fact based on servitude and the alienation of bodies for economic ends by the Masters and on a selection of the workforce and thus inter-group competition, generating practices of social differentiation. All the components of the settlement of Reunion thus experienced it.

The “poor whites” (Petits Blancs) –petits créoles–, ont cohabité avec les esclaves, alliés de manière équivoque . Certain practices, attitudes or mental representations bear witness to these experiences.

In the archives, the recurring frequency of the verb amarrer (to moor) caught my attention, firstly, through the use of this Creole term, synonym of to tie up, bind or attach, in French. Secondly, it is used to describe a situation of humiliation through bodily constraint. In 1904, the brigadier forest ranger of Grand Tampon, prevented from walking across the property of one of the inhabitants who was hostile to the Eaux et Forêts (forestry department), wrote: “We have no intention of letting ourselves be bound that by these settlers”, the reason why he decided to cease the surveillance. In the second occurrence of the term, appearing in 1906, the threat made by a Mayor in the west of the island questioning a fine imposed for an offence committed by agents working for the forestry department is expressed in these terms: “I have the right to have you bound up and taken to the police station by simple drivers.” In fact, in the reports of interrogations of slaves studied by Prosper Eve, the verb is associated with loss of dignity when slaves were arrested and were bound up (amarrés). In 1798, the interrogation of Marcel, suspected of being a maroon slave, closes in the following terms: “The citizen Hoareau came across some blacks who helped him to bind up the slave. I noted other marks of continuation of the system of slavery in our society in conversations presented as a survey on the memory of slavery. It was spontaneously associated with working under constraint: the situation of the settler for the grandfather of one of the women questioned; the load carried by the porter in Salazie for another.

A past that can be inhabited by all should thus be based on genealogical experiences or not, in order to produce a clear vision of the social edifice constructed through slavery. It is thus a common narrative that will make it possible to inhabit this past.