“Our population consists of two classes of persons that are so fundamentally dissimilar that one would think they were the product of two different creations.” These were the words used by the general counsel Gillot L’Etang when welcoming the new governor Achille-Guy-Marie de Cheffontaines to Bourbon island, future Reunion island, on 20th October 1826. His speech sets the tone of State racism during that period and gives an idea of the huge task to be undertaken to achieve a harmonious society on the island, following the dismantling of the system of slavery.

As from the 16th century, in the hot-climate profit-making colonies, slavery was a European phenomenon. It took root in the wake of the Columbian route towards the American continent as from 1492, following the inaugural voyage of Christopher Columbus, as well as along the Da Gama way towards the Indian Ocean as from 1497, following the arrival in that part of the world of the admiral Vasco de Gama. It was justified by the double climatic and racial determinism, as well as by economic realism, that is to say by geographic factors, in the context of a commercial process that we can consider to have been the first globalisation of trade. The African or Black became the engine of the process of production of colonial goods of high added value, aimed at European markets. A low-cost labour force for production in sunny lands, the African was bought and sold as though he were a machine or tool. Louis XIV, the Sunshine King, in a decree he issued on 26th August 1670 declared: “There is nothing that makes a greater contribution to developing the colonies and working the land then the hard work of the Africans.” For almost two centuries, until 1848, the greatness of France depended on the labour of African slaves. Eventually, the phenomenon was recognised as being ‘a crime against humanity’. This is the accepted basic notion. However, everything has not been said. It was the beginning of a European history of racism that differentiated and ostracised, at the heart of suffering perpetrated by northern states which, in the following century, led to other crimes against humanity.

“Now he is destroyed, I am once more a man”, declared a character from Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Habermas told us that in dark times, we must examine the European mentality: “The psychology of the period is difficult to explain.” Of course, he was concerned with a period other than slavery, but was referring to the same tentacular temptation in Europe to consider others as inferior, with the shedding of blood, the ‘impure blood’ of Shylock the Jew and Caliban the Black, two other characters from Shakespeare’s 17th-century plays. The endless appetite of the Erl-King in the German tales is insatiable. European activity in “the hot blue countries” (Baudelaire) focuses on the “Calibanisation” (Césaire), of the colonial constraint and civilisation, seen as “The white man’s burden” (Kipling).

The present text is organised around two sections. The first part analyses the arbitrary process that eliminates a part of the living being from humanity and history. It then treats the return of Reunionese Man in his history through the construction of Creolisation, the process of mingling of bodies and imaginations. The text is a homage to Pierre Bourdieu, for the 20th anniversary of his death (2002-2022); the sociologist analysed domination in the field of gender through “the biological process of the social”, insisting on demonstrating that history is not limited to change and that it is often the ceaseless reproduction of the same process over time: the same way of seeing the other and the same vision of the other. This oppressive and arbitrary point of view can feed into the racism of another period, with its roots in the dawn of time, giving birth to today’s models of analysis and behaviour.

Each discipline has its own epistemic form, which contributes to its vision of the world. Geography is within its own field when, as a bio-political science, it treats the process of organisation of space and Man. For a long time, it shared with the sociology of Gabriel Tarde (Monadologie et sociologie, 1893) a functional identity consisting of “total and universal knowledge, written in a specific language” (Gilles Bastin, Le Monde, 6th April 2017).

Eliminating slavery in France goes back along way in time. In 649, it was imposed by Bathilde, Queen of France, a former slave whose freedom had been purchased, and by the edict of 3rd July 1315, signed by Louis X. The enslavement of Africans appeared in the 16th century, replacing the servitude and forms of subjection practised in Antiquity. It went hand-in-hand with European expansion in tropical regions. Everything could be seized when diverting this crazy economy of hunting and gathering: the African, the African’s children and the African’s territory. The politics of colonial discord was set up with the the two shadows it cast: the Calibanisation of the African, that is to say natural submissiveness based on presupposed ideas of race and the civilisation of the white man, that combination of strength, grandeur and cunning, an illusion that subsisted for centuries.

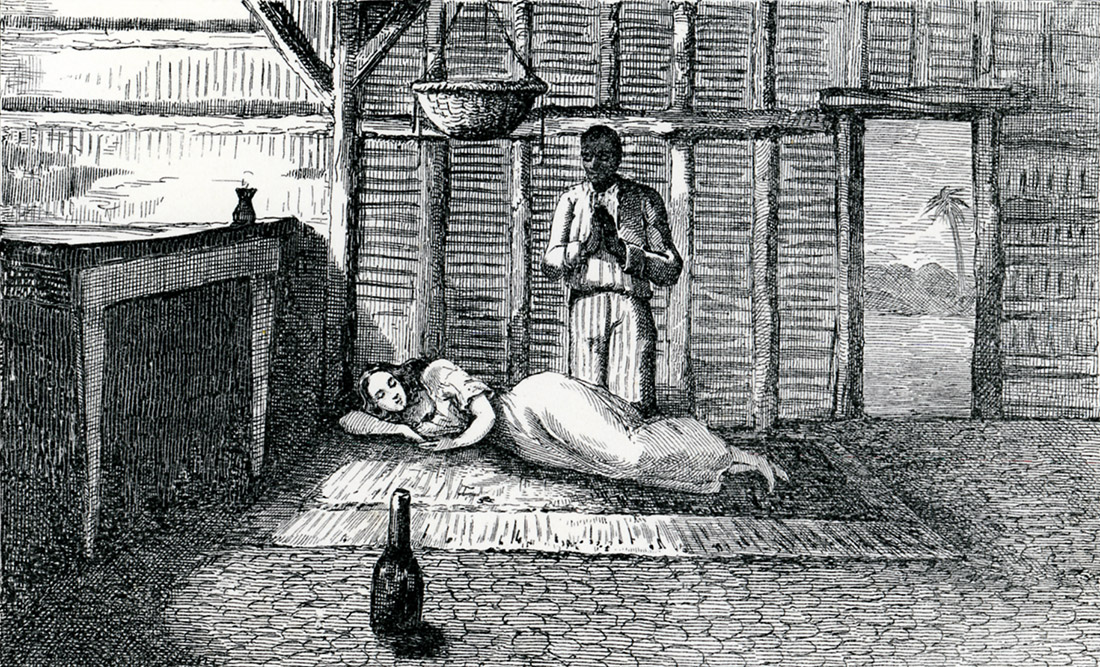

In France, the 1st Republic abolished slavery on 4th February 1794, before re-establishing it on 20th May 1802, each time in the name of the people of France. In the face of economic lobbies, the Republic, as well as the Church, sometimes gave way: the former on the pretext of liberating people from their savage society and bringing them into civilisation, the latter through the construction of a discourse around saving the souls of Africans. Pope Eugene IV, in his encyclical Sicut dudum dated 13th January 1435, then Pope Pius II in a letter entitled Rubicensem addressed to the Bishop of Guinea on 7th October 1462, qualified the slave trade as magnum scelus (grand crime), with the Church taking position against the enslavement of Africans. In the meantime, on 8th January 1454, Nicolas V, in his papal bull Romanus pontifex, authorised Alphonse V, King of Portugal, to trade in “blacks from Guinea and pagans”. In this context of prejudices, in 1611, the European imagination created in the theatre a being born of Evil and bestiality: Caliban. Son of a witch, living submitted to Prosperous, a white magician, the character from Shakespeare’s play The Tempest incarnated, in all its ambiguity and ambivalence, the uncivilised black man and pure force at the service of white intelligence. He is the tropical man-beast, purchased and purchasable to carry out extenuating labours under the sun, Césaire seeing him as the eternal rebel. Césaire defines the process of servitude and domestication as ‘Calibanisation’. Submissiveness is marked by fall. The place of Africans is to be under the orders, under the whip and under the bodies of others.

Haunted by absences, the uprooted slave takes on the status of ultimate orphan, relegated to the dark recesses of imagination, marked by self pity, mourning, mute silences and perpetual injustice, a combination which confirms the image of a person devoid of reason.

The French ‘Code Noir’, the legal document determining the status of slaves in the Indian Ocean was signed in Versailles on 18th December 1723 by Louis XV, a 13-year-old boy-king. It was recorded by the Higher Council of Bourbon island on 18th September 1724, and is dated that year. While all reference to Jews and Protestants, ostracised by the Atlantic ‘Code Noir’ of 1685 had been removed, segregation is at the heart of the defined social structure: “We must forbid our white subjects of either sex to contract marriage with Africans, actions liable to punishment and arbitrary fines and for all secular or regular vicars, priests or missionaries and even ships’ chaplains to marry them.” (Art 5). The article reflects the philosophy and the terms of article 20 of the Grande Ordonnance issued by Jacob de la Haye dated 1st December 1674: “It is forbidden for French men to marry African women, as this would turn Africans away from their service, and it is forbidden for Africans to marry white women; such confusion is to be avoided.”

The topic of the desire for a white woman was treated in literature. In Bug-Jargal, (1820), his first novel, set in the island of Saint Domingo, where there is an insurrection, Victor Hugo depicts the platonic love between Pierrot, a black slave in love with Marie, the daughter of his white master. He will renounce his white love, leaving her to his white rival Léopold d’Auverney, with whom he will form a brotherly relationship. His sacrificial suicide announces the creation of a new world and of the image of the romantic African. In 1844, Houat treats the same topic in Les Marrons, considerd to be the first Reunionese novel. Frême, the African in the colonial workshop, does not renounce his love for a white woman and runs away with Marie. They will be hunted down like dogs. The abridged work on the history of the island and its literature was rehabilitated by the sociologist Raoul Lucas.

The 1724 Code Noir does not give a legal definition of the white man and creates uncertainty concerning the slave. Is the latter a person, a child of God through a Catholic baptism (Art 1) or mobile goods (Art 39)? Indirectly, it questions the identity of the white man and creates two rebellious characters committed to heroism in the society: the maroon (fugitive) slave and the abolitionist priest. The ‘Code Noir’ meant that maroonage was the only way to escape from slavery and reintegrate active humanity. “There is no doubt that the intention of the legislator in 1723 did indeed consist in organising a society openly built on racist considerations, ensuring the domination of the white man over the black man,” states the legal expert Laurent Sermet (1998). He notes the absence of any legal definition of the slave, recognised indirectly through a certain number of hypotheses. The slave is one who is sold, bought, dominated, used as an ‘object or mobile goods’. He or she thus has no rights. Reading between the lines, he is, a priori, Black, and consequently any black man on the planet could be a slave. The white man apparently belongs to the class owners of land and men who buy them, sell them, give them away and emancipate them at his whim. According to Father Joffard, all black slaves can become whites like him by being made free (Declaration dated 18th June 1848 in Saint-Philippe).

In the face of ‘the confusion’ feared by Jacob de la Haye in 1674 concerning the White/Black relationship, 19th-century researchers attempted to introduce some order and ranking into this profusion of mingling of bodies, resulting from transgressions of la Grande Ordonnance. Thus William Duckett (Le Dictionnaire de la conversation et de la lecture, 1832-1852) proposed labelling based on the proportion of the individual’s blood that was white. The value scale includes the ‘terceron’ (3/4 white), the ‘mulâtre’ (mulatto) (1/2 white), the quaterton, an old unit of measure equivalent to a quarter of a pound, used to describe a person born of the union between a white man or woman with a person of mixed race (1/8 white), the ‘quinteron’ (1/6 white) and then the scale goes down, progressively darker, as far as the ‘octoron’. Certain terms are reserved for specialists: ‘griffe’ or ‘zambo’ (1/4 white) or ‘quarterton saltatras’ for ‘backward leap’.

In his work Pièges et difficultés de la langue française (1986), Jean Girodet declares we must distinguish ‘métis’ (of mixed race), ‘mulâtre’ (mulatto) and Creole. The ‘métis’ is born of a father and mother belonging to two different races, whatever their races; the mulatto is born of one black parent and one white parent; the Creole is ‘a person of white race born in the Caribbean or Reunion. It should never be used in reference to a person of mixed race or a mulatto’.

In their colonial expansion, the French encountered exoticism, the clash of civilisations and dissimilar groups of men. Over four centuries, from the 16th to the 20th century, France had long-term issues with Africans. According to Marcus Rediker (A bord du négrier, une histoire atlantique de la traite, 2013), it was slavery that forged the concept of race, enabling France to clarify its position and construct its theory of separate development. It was necessary first of all to set up distinctions between the Black slaves. Race became colour! It was no longer a geographic concept as it had been in the 18th century descriptions by Linné. While the race of all the slaves was defined as “black’, the term ‘caste’ appeared in the official documents of sale, loss, escape or emancipation, in an effort to define a precise identity. It often referred to geographic origin. Thus, according to decree N° 597 dated 27th October 1844 of the Official Bulletin of Bourbon island, Ragotin was of the Yambane caste, Zélina of the Madagascan caste, Geneviève of the Creole caste, that is to say born on the island. The word comes from the Portuguese casta meaning ‘pure, not mixed’, and refers to a hierarchical, endogamous and hereditary social group.

Collection of Reunion Departmental Archives

The return of the Reunionese Man in his history is a theory that was put forward by Éric Boyer, President of the General Council of Reunion as from 1988. It is to be understood through the notion of ‘duty of memory’, through Creolisation, that is the say the death of Calibanisation, then through the inauguration of the new era, referred to as ‘the era of ourselves’, a formula used by Césaire. This return makes it possible to construct a more equal Reunionese society. The return of the Reunionese Man in history must be analysed in relation to a speech made by the French president Sarkozy on 27th July 2007 at the University of Anta Diop in Dakar, declaring that “The tragedy of Africa is that the African man has not been sufficiently present in history’, a statement that provoked mixed reactions.

‘Duty of memory’ is a wonderful expression! It became a key term of the policy of commemoration by the French state, opening doors and drawers full of memories. Sébastien Ledoux (Le Devoir de mémoire, une formule et son histoire, 2016) dates this use of the operational character of the term as a lever for a memorial policy back to the 1990s. Initially used by academics, the term filtered down into the media, ideas and political discourse, with the mechanical certainty of its obvious relevance. Law N° 83-550 dated 30th June 1983, concerning the commemoration of the abolition of slavery and homage to be given to its victims, institutionalised “a public holiday in the French Departments of Guadeloupe, Guyane, Martinique and Reunion and in the territory of Mayotte”. Decree N° 83-1003 dated 23rd November 1983 determined the date of this commemoration for each of the Territories, since no one day received unanimous approval. In the Reunion, the date is 20th December. While there is unity of action to identify French colonial slavery, there is no unity of time and place in distant geographic regions for organising the commemoration.

Through law N° 2001-434 dated 21st May 2001, the French Republic recognised that the slave trade and slavery “perpetrated as from the 15th Century in America, the Caribbean, the Indian Ocean and Europe against the African, American Indian, Madagascan and Indian populations, were crimes against humanity.” (Art 1). An application for recognition by Council of Europe and the United Nations (Art 3), as well as the inclusion in school curricula (Art 2) completed the legislative structure. In addition, the law dated 29th July 1881 was modified in its article 48-1 to include the notion of “defending the memory of slaves and honouring their descendants.”

Reparation demanded for offence against humanity at times takes a surprising turn: a new text contributes to the expiatory erosion. Thus, the law dated 27th January 2017 concerning equal citizenship, in its article 219, repealed law N°285 dated 30th April 1849 concerning compensation granted to settlers following the abolition of slavery. These repeated modifications will probably one day have the effect of preventing new grass growing and an understanding of all the fires of the past season.

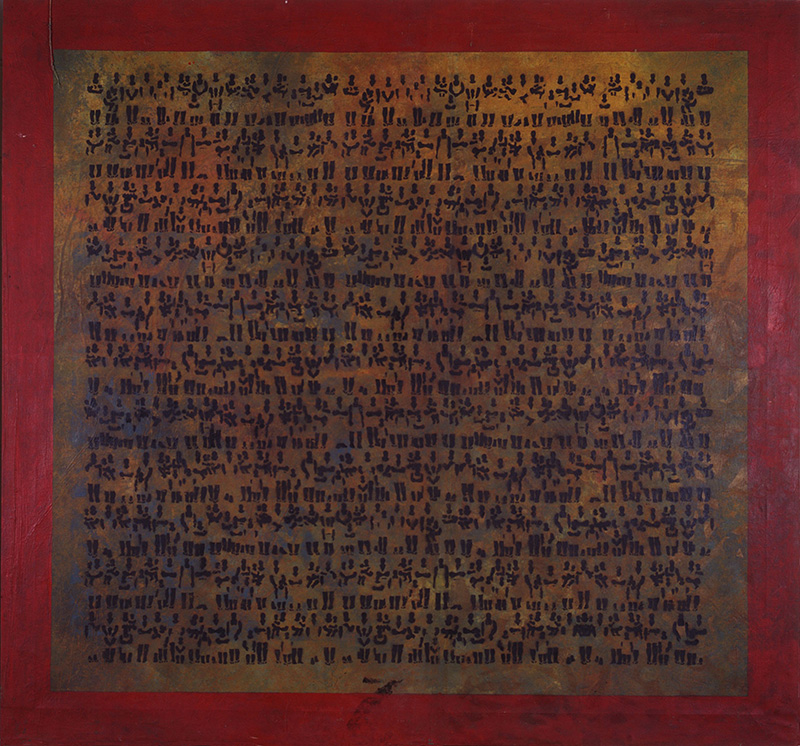

The distressed slave, cut off from his dead ancestors and his words, transferred from dhows to the bottom of the holds of other slave ships, needed to open up a new dialogue in Reunion, renewing everything on the basis of supplication and prayer. This was the price to be paid for coming back to life, since here, not everyone spoke the same language but everyone had to live together. Languages are never interchangeable, always carrying the cultures of different civilisations. So when the dialogue became ethical and impoverished in the language of the other, the temptation was to adopt borrowed words, each person contracting debts with adopted images, depending on the tastes and emotional intelligence of each, until the creation of an orgasmic organism: the Creole language.

Creolisation is the whole process of mixing bodies and imaginations, creating metamorphoses and new metaphoric realities, products of contact, touch and intrusion. It is through touch that attachment to a new land is created. In Reunion, the Creole word became flesh in a co-existential adventure, since, as we remember those forgotten lives, through the cracks of the official history of the slave trade, as we reawaken our dead, for whom we will always feel pain, we must celebrate the rebirth of the self through a new vocabulary. That is how the protagonist populations, including those born out of the slave trade “will speak up, above the noise of the disasters”, to quote Césaire.

In a parting letter written to Maurice Thorez, head of the French Communist Party, aimed at breaking away from the failings of the 4th Republic and its old peripheral slave-trading commercial links, Césaire declared: “The time for ourselves has come”. He proposed constructing “ourselves”, within the liberty of all the “myselves”; he proposed building the French Nation with the halos of distance, with a sense of the shameful and incontinent stains left in the bed of the past, and with the aura of a prestigious centre, as expressed by Walter Benjamin and represented by the Republic. Symbolically, Césaire, a poet acting in the political arena, considered that, as a lesson in humanity, margins are essential, enabling the page to exist. For the new republican pact, it was necessary to become insensitive to the pains of the past, pushing back our rancour and reconstructing the concept and the reflexes of autonomy and responsibility, forgiving the Republic for its imperfections. According to him “to hate is to continue to be dependent.”

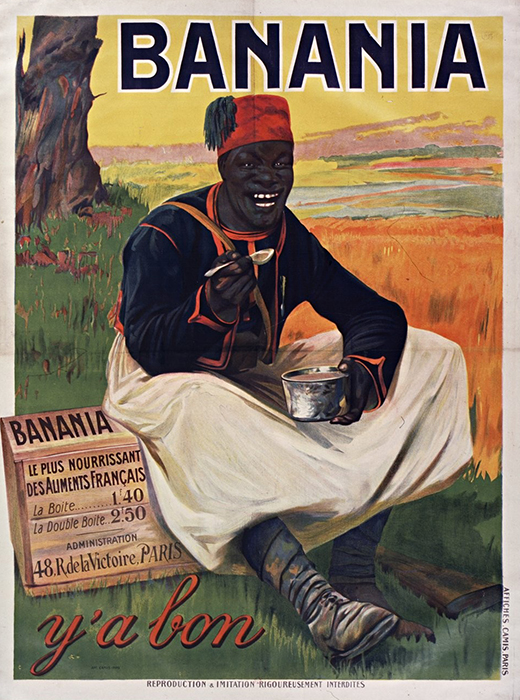

In a France of consumerism, for a long time persisted the image of the smiling, happy subordinate African, wearing the red infantryman’s box-hat, a sort of condensed version of the history of the French colonies. The ‘Banania African’, an image used in publicity for a chocolate drink, was considered neither wrong nor irreverent. The sociologists Bourdieu and Luc Boltanski, in their work Production de l’idéologie dominante (1976) had, however, warned us against such condescending manipulation. The MRAP (an anti-racist movement) decided to sue the company Nutrimaine for using the image of the ‘Noir Banania’ African, considered to be racist and an infringement of human dignity. On 20th May 2011, they won the court case. The image and the slogan (‘Y a bon Banania’) were seen as projecting an outdated clichéd image of the African, eternally standing on the doorstep of the civilised world. “An African can only speak a very simplified form of French,” argued David Marty, the barrister defending the MRAP.

What is the point of today’s debate around slavery? Beyond the exercise of transmission, it can contribute to creating a fairer society. This fairer society is based on two important principles: the right to freedom and the right to be different. The principle of freedom gives each person identical rights based on equality between all individuals. The principle of difference is justified through the existence, in the same political group, of men and women who do not have the same history or the same geography and who do not share the same past, the same sea, the same food and the same language. All French people do not have the same identity. Identity is always the result of what happens between ourselves and others through touch; this journey refers us back to the image of water, having no scent and no colour but absorbing the taste and colour of what it encounters. And in the heat of the tropics, far from the snows of yesterday and the distant regions, the men and women here in Reunion experienced other encounters, other situations: slavery and the Creole utopia, the latter term which apparently means illusion but which actually signifies hope. For the exchange to be effective, the philosopher Georges Didi−Huberman exhorts us to together reconsider the past, the present and the future, so that we may successfully apply the perilous lesson presented by all forms of transmission.