This was a necessity due to the conditions of navigation during that period; ships would sail into these seas following a four to five-month journey and crews would, of course, need to replenish their food stocks. The great danger facing those undertaking the long journey was the onset of scurvy, an epidemic disease caused by a lack of vitamins, particularly vitamin C, for which the only known remedy was distribution of recently-harvested food products rich in vitamins. They would also need to renew their stocks of water (5 litres per day for each man), as well as wood for cooking. At times, it was also necessary to carry out reparations to the ship.

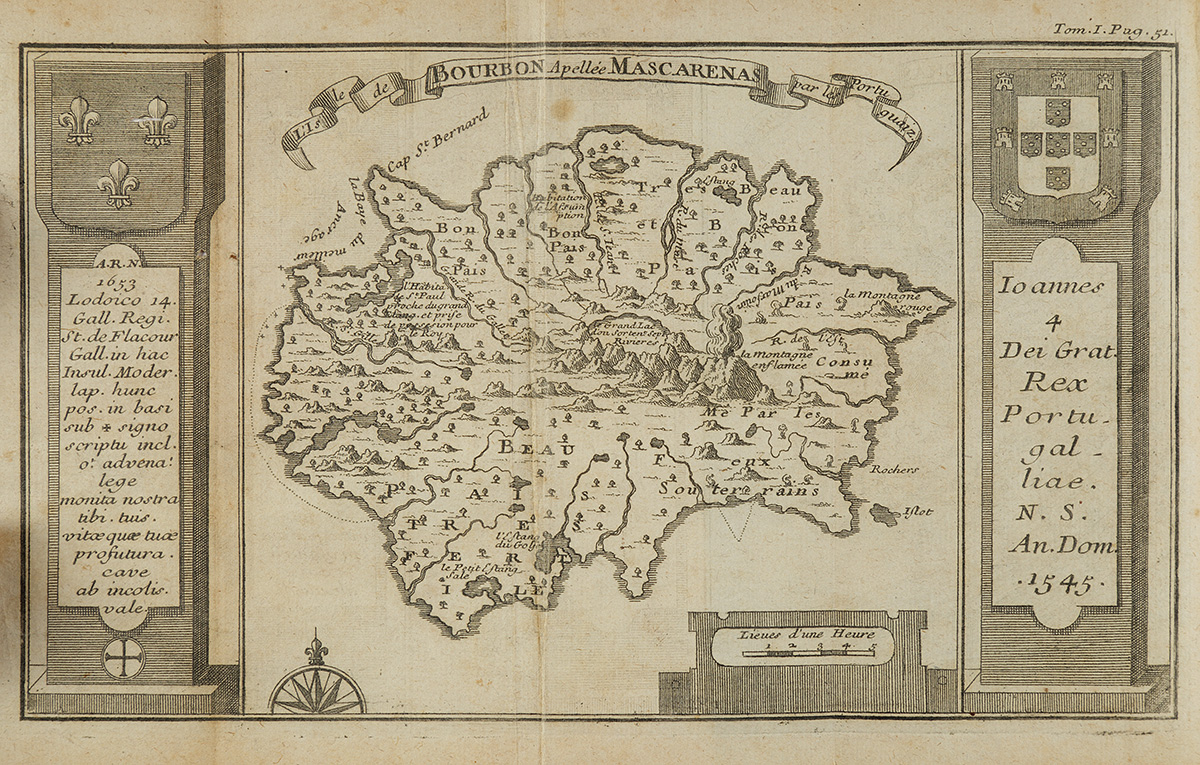

The French had been sailing this route at various times since the 17th century and would often moor along the coast of Madagascar where they could find the necessary ‘replenishments’. In 1642, Richelieu, wishing to give the trade between France and eastern Asia a certain permanent character, founded the Oriental Company and established Fort-Dauphin (named in honour of the young Louis XIV) in the south-east of Madagascar. In addition, he proposed to take possession of the island of Mascarin, which the governor Flacourt named Bourbon since he “could find no more appropriate name to express its bounty and fertility”. The island had, until then, been free of all European presence, since its coasts offered no natural form of shelter.

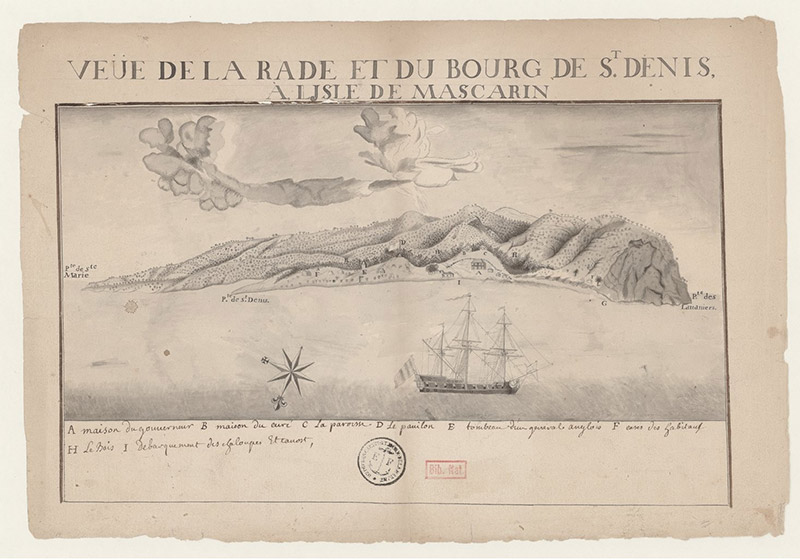

Under French ownership, the island was occasionally visited by sick sailors needing rest, as well as various ‘undesirable’ members of the society, outcasts sent away from Fort-Dauphin. In 1663, following the request of the marshal of La Meilleraye, the Company’s main shareholder, the directors decided to set up a military base on the island, declaring: “…the place is very healthy, very fertile and offers very abundant meat and fish.”

In 1664, the Oriental Company merged with the prestigious East India Company, founded by Colbert, the general controller of finances, with the aim of competing with the very active Dutch company bearing the same name. The minister’s dream was to turn Fort-Dauphin into a new Batavia (capital of the Dutch East Indies, now Jakarta), an influential port trading over the whole of the Indian Ocean, but he did not manage to obtain the necessary capital for the project and the French trading post went through a period of stagnation. In 1674, following a period of conflict between the Madagascan population and the French settlers, during which several of the latter were slaughtered, many of the surviving French decided to leave Fort-Dauphin to settle elsewhere, notably on Bourbon island.

The lack of funds, as well as the virtually constant wars between the French and Dutch, prevented the development of the island. At the start of the 18th-century, after 40 years of European presence, the island had 1,100 inhabitants, many of whom were born there, as few new settlers arrived during this period1. Despite the abundance of game and fruit, captains of sailing ships would hesitate to moor along its coasts, since agricultural activity, as yet hardly developed, meant that availability of food was unreliable. Over a period of 40 years, only ten vessels sailing from France and twenty sailing in the other direction stopped off at Bourbon island. The administration of the East India Company and the settlers possessed neither the funds nor even the willpower to apply any changes that might improve the situation.

Change arrived in the form of repented pirates. Around 1685, large-scale piracy, up until then present in the tropical islands around America, became active in the Indian Ocean. The filibusters had heard that cargos bearing precious metals of great value were being transported by European ships sailing east to buy oriental products and they sailed into the area to attack them. Between forays, they took shelter and rested along the coasts of Madagascar, ideally situated on the routes between Europe and Asia, another advantage being that there was no longer any authority applying justice there. The pirates also needed manufactured products from Europe. Not lacking money, they would stop off on Bourbon island, where they were given a warm welcome. Some, attracted by conditions of life on the island, decided to settle for good. In 1687, the governor transmitted to the directors of the East India Company a request for settlement made by six repentant Dutch pirates, a request which was accepted. Later, in reply to missionary priests expressing concerns that “… these boars will demolish the vines of Lord”, Antoine Boucher, deputy governor, replied “They mustn’t forget that the best of the inhabitants of Bourbon island used to be pirates.”2

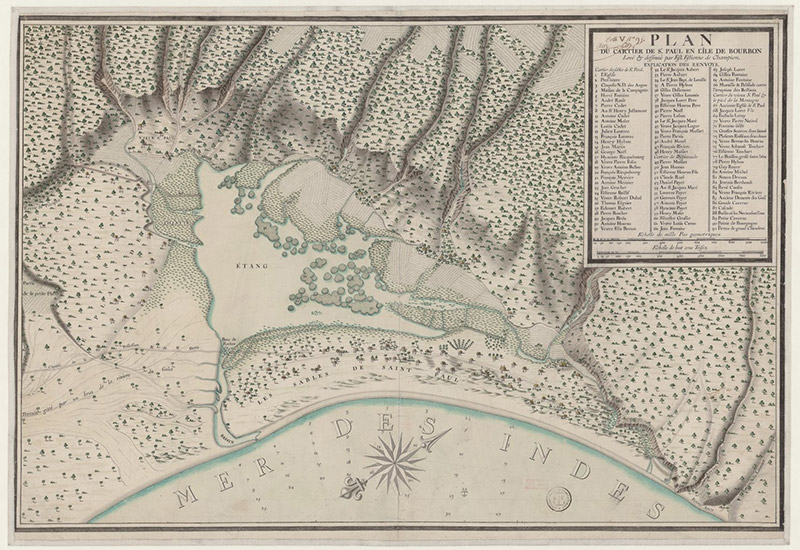

In 1710, at the request of the directors of the French East India Company, the same Antoine Boucher issued a Brief to the intention of each inhabitant of Bourbon island3, giving precise figures. A large number were former pirates: 40 out of 121 heads of households, representing 48% of the inhabitants; they were rich: Jacques Siboalle from Provence possessed 13,500 French pounds and Rabin from Scotland 12,000 pounds. They would use their wealth to buy slaves to clear the land and start growing crops; above all, they contributed a spirit of enterprise, which had a decisive effect on the island.

The Brief bears witness to a renewed interest shown by the directors of the French East India Company in the development of Bourbon island. During this period, the financial situation improved as a result of a transfer of the trade monopoly between eastern India and France to a group of ship-owners in Saint-Malo, associated with the financer Crozat. In December 1709, the directors appointed Louis Boyvin d’Hardancourt, son of the Company’s general secretary as “general commissioner for visiting the French East India Company’s establishments”, with the aim of obtaining “more exact and more reliable” information. Louis Boyvin remained on Bourbon island from April to September 1711, visiting the entire territory. Following his stay, he issued two proposals:4

1° “The impossibility of creating a harbour on Bourbon island has led me to take a look at the island of Mauritius, deserted and abandoned by the Dutch a few years ago (1710) (that the Dutch deserted in 1710). I consider that the French East India Company could do worse than to set up a solid base there for the replenishment of its ships, where they will be safe in the island’s two harbours.

2° I have never doubted the success of planting coffee on the island. Proof of this is the existence of wild coffee plants that I have found growing on the flat mountain areas behind Saint-Paul.”

These two proposals, accepted by the Company and approved by the king’s council, were immediately implemented. A vessel was sent to Mauritius and took possession of the island, which was named ‘Ile de France’; another ship loaded 60 coffee plants at Moka (Mauritius), sailing with them to Bourbon in September 1715. Of the 20 trees that had survived the journey, only two took root, starting the production of the ‘Bourbon rond’ strain of coffee. Growing of the local ‘Bourbon pointu’ strain was abandoned, since yields were irregular and the aroma little appreciated. Antoine Boucher, deputy governor, who later became governor of the island, calmed the impatience of the directors and stubbornly continued to develop the crop5. The first cargo – 3,400 pounds in weight – left the island in 1724. Followed a period of rapid growth, with 100,000 pounds in 1727. “The crop is at last a success and the Company can now expect rich harvests and will be able to cover the investments made,” wrote the directors after unloading 900,000 pounds in 1734. The Company took delivery of 1,500,000 in 1740, 2,500,00 in 1744 and in the years to follow, an annual production of between 2,000,000 and 2,500,000 pounds.

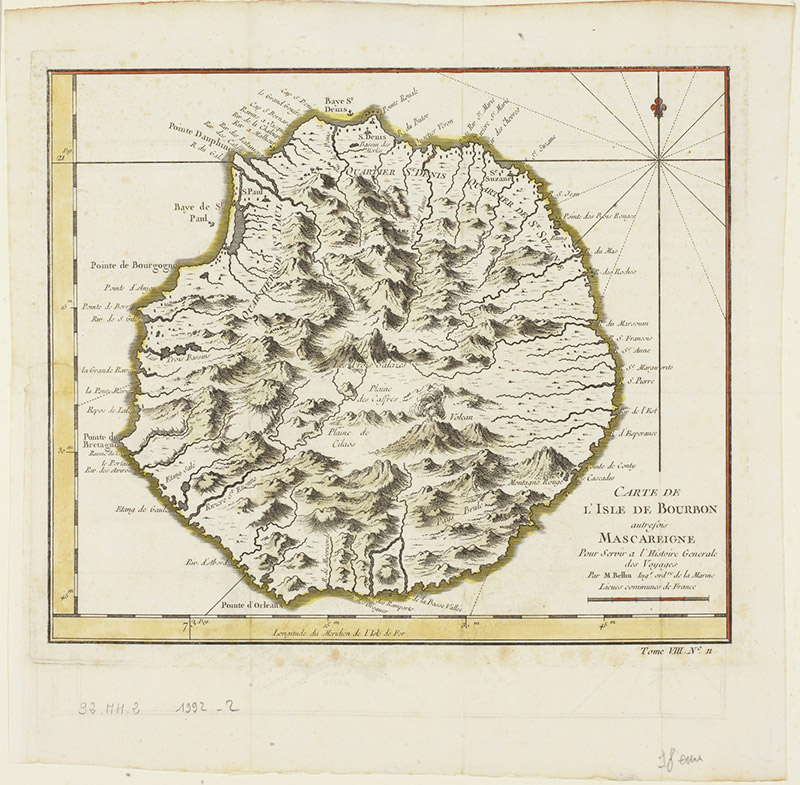

The whole of the coastal plain around Bourbon island was progressively transformed, as settlers gradually moved from Saint-Paul and Saint-Denis. The parishes of Saint-Louis and Sainte-Suzanne were created in 1728, Sainte-Marie in 1733, Saint-Benoît in 1734, Saint-Pierre in 1735 and Saint-André in 1740.

Agriculture transformed the landscape. Along the coasts, land surveyors staked out the ‘Company paces’, the latter being a strip of land measuring 50 paces, approximately 80 metres, protected by ‘upright timber’ with the aim of contributing to defence in the event of an enemy attack. The remaining land, stretching from this plot to the foot of the ‘cliff’, which was the outside limit of the mountainous zone, was divided up into ‘concessions’. These were fairly narrow strips of land, 25 to 125 m, but very long, sometimes covering several kilometres, since these covered the whole area between two gullies. The area of each varied greatly, the more so as from 1732, in the areas newly cropped, the surveyors, at the request of the Company, would trace out four lines parallel to the shore and to the ‘Company paces’, at altitudes of 100, 200, 400 and 600 m, in order to create small-sized concessions.

To this day, these are often still marked out in the current division of land, since they form the boundary between plots and are now marked by paths or roads.

The slaves, now numerous, would clear the land and grow crops. When the East India Company was set up in 1664, the monarchy had forbidden the practice of slavery:

It is expressly forbidden to sell any inhabitant of the country as a slave. Any person who does so is liable to capital punishment and any French person hiring them or retaining them in their service is enjoined to treat them in a humanitarian manner, without molestation or insult, or otherwise be liable to corporal punishment.7

However, the ‘servants’ listed in the first censuses carried out appear to have had a way of life close to that of slaves. The word ‘slave’ was first used in 1690 in official correspondence, and in the censuses of 1713-1714. With the development of coffee-growing, the directors of the French East India Company requested of the king a regulatory text making it possible to practise slavery in the islands of the Indian Ocean. The text, largely based on the ‘Code Noir’ (black code), issued in 1685 for the American islands, was published in December 1723.8

From that date on, the Company organised annual slave-trading expeditions, selling slaves to landowners. In 1723 there were approximately 600 slaves, for a total population of 1,200 persons. In 1730, there were 4.000 slaves on the island, representing over 80 % of the total population of 4,800. The same percentage was maintained throughout the rest of the 18th century, with 8,000 slaves for a population of 10,000 inhabitants in 1740 ; 11,000 for 13,500 in 1750 ; 15,800 for 20,000 in 1764.

The island’s slaves originated mainly from Madagascar (64 % in 1735). The Company kept an outpost with a permanent officer at Foulepointe, to the north of the current port of Tamatave. Slaves captured in Madagascar were preferred, since there were fewer deaths during the crossing (close to the number of Europeans with 12%, while the number of deaths reached 21% during journeys from the east coast of Africa), even though the French settlers always feared the slaves stealing a boat to sail back to their native country. During the second half of the 18th century, little by little mixed-race persons started to form an important minority of the population (over 30 % in 1762). There were few slaves of Indian origin – always under 5% – with frequent hesitation regarding their status, whether they were to be considered as slaves or free craftsmen. Virtually no slaves were freed during this period, the Company being opposed to the idea.

The day-to-day living conditions were set out in an edict issued in 1723. As in the Carribean, the slave was considered to be a ‘belonging’, not recognised as legally capable and having no right to property apart from a limited ‘allowance’. The master was responsible for his or her slaves’ actions and owed them protection and food. The daily amount of food, set out in the edict, was one and a half pounds of rice for a man and one pound for a woman; the master was responsible for the upkeep of any old or disabled slaves. The slave was to receive religious education and was not to be made to work on Sundays or religious holidays. It was forbidden to sell the husband, the wife and their children separately. Punishment was limited to flogging, but severer punishments were to be inflicted in the event of theft, unauthorised gatherings or any attempt to escape.

It is difficult to assess the true living conditions from these legal elements. The following text, written by a master who was later denounced for his severity, can give us some idea:

Regulations concerning black persons belonging to Sr. Desruisseaux. – Article one. Any black person going out at night without the master’s permission or that of his representative will, for the first offence, sleep in the dungeon for one night, for a second offence 8 days, a third offence one month and at the 4th will be chained up for one month.

Article 2. Those caught stealing from the neighbours or the master will, for the first offence spend 8 days in the dungeon, the second time 15 days and the third will be chained up for 14 days.

Article 3. Those attempting to escape will be punished with 30 lashes of the whip for the 1st attempt, for the second, they will be chained up for 15 days and sleep in the dungeon for one month.

Article 4. Any black person carrying out second-hand trade with his comrades, buying or selling without the master’s permission, will be punished with 30 lashes of the whip.

Article 5. No black person, even the foreman, may sleep elsewhere without the master’s permission, for whatever reason. Those wishing to sleep elsewhere after work must inform the master or his representative or receive 20 lashes of the whip for the first offence.

Article 6. My black slaves may not receive any outside black persons in their house or hut without informing the master.

Article 7. Any guardian catching a thief in my house will be rewarded with a handkerchief. If the thief is a runaway slave, the guardian may keep him or her.9

Despite the punishments, encouraged by the uneven terrain of the higher parts of the island, slaves continued to attempt escape. It is difficult to assess the exact number of fugitives, since many of them would return following a few days of freedom. La Bourdonnais estimated the number to be 200 in 1735. They often lived in armed groups and would come down to the coast to obtain supplies of tools, weapons and women. Some settlers were killed when they came across the fugitives and attempted to stand up to them, a fate that befell Brossard en 1732 and François Moy in 1737. Following these assassinations, the settlers organised armed militia acting under the orders of the local captain, who was generally a former officer of the French East India Company. They would organise forays into the mountains to capture fugitives and destroy their settlements. The process appeared to be met with success and by the mid 18th century, the danger represented by escaped slaves was far less serious.

The difficulties of the slaves’ living conditions must not be exaggerated. The life expectancy of the slaves on Bourbon island was higher that that of the slaves kept on the American islands, with over half of the men on Bourbon island reaching over 40 in 1765. During the first half of the 18th century, family life, at least, was common (over 80% of the children in the parish of Saint-Paul were born to a legitimate father), which was an element of stability. However, as a result of the economic decline, it was probably less common during the second half of the 18th century.

With the development of the coffee crop and the success of the plantations, the number of settlers grew. With a modest increase of 600 to 800 settlers between 1720 and 1730, the population grew to 2,000 in 1740, 2,500 in 1750, with the growth continuing at a similar rate to reach 4,000 settlers in 1764.

40% of the settlers were employees or former employees of the French East India Company, working in administration or the army. In addition, members of the nobility were greater in number on Bourbon island than in the provinces of mainland France. During the 1776 census, 6,000 white people were listed, belonging to 700 European families and 35 of these families were qualified as nobles or knights, representing 5% of the population, far higher than that of the nobles in French mainland society. The island’s nobles were often the youngest members of their families taking advantage of an allowance paid regularly by the East India Company, a structure close to that of the monarchy, and then, as from 1766, by the sovereign himself, while at the same time developing an estate on the island.

“You do not come to the Indias only to do business,”10 wrote the governor La Bourdonnais in a Brief addressed to the Ministry of Finance. “The contrary opinion, not being natural, may not be expressed.”11 The settlers came to make their fortune. Certain were talented, which was the case of the governor Benoît Dumas. When he was sent to the islands in 1727, the general directors issued the following order:

Mr Dumas having declared to the Company his intention of setting up habitations for his personal account, the Company orders that should be made available to him, in areas that have not yet been divided up, concessions of land on Bourbon island of the same size as that given over to the defunct Mr Boucher and in the same conditions and at the same price as for the other inhabitants.

In addition, for 20,000 French pounds, Dumas bought land in the process of being cleared that the owners had decided to abandon, and between 1727 and 1732, he bought 143 slaves for 50,000 pounds, representing a total outlay of 70,000 pounds. Appointed governor of Pondicherry in 1735, he sold it all for 150,000 French pounds. In a period of less than eight years, he therefore doubled his fortune.12 The outlook at the time was very positive, as was indicated in 1756 by a notary on this island: “It is well-known that investments made on the island produce (annually) over ten per cent”13, whereas investments made in mainland France are close to 5%. With the exception of those who married a wealthy Creole lady owning a house (generally 10-15 years younger than the husband), the main difficulty consisted in settlers incurring debts. Concessions were granted free of charge, but it was necessary to have some capital in order to purchase slaves, which were expensive, and begin growing crops within a period of three years, in accordance with regulations. The officer Balame de Montigny, for example, was put in prison, where he died, for being unable to pay a debt contracted for the purchase of 20 slaves; in 1747, the officer Denis d’Acqueville died following a two-year stay on the island, having previously obtained a concession and purchased 29 slaves, leaving liabilities of 17,819.04 pounds for assets of 13,245 pounds; Joseph Dacian, a clerk, died after four years on the island leaving a fortune of 9,821 pounds and 5,527 pounds in debts, representing 56% of his assets; in the same year, the clerk François Mathieu died after 10 years of residence with assets of 23,332 pounds and 15,878 in liabilities, representing debts of 68%14. There were always success stories, such as that of François Bertin, former commander of the island, who, after returning to mainland France in 1767, bought the position of King’s secretary for the sum of 105,000 pounds, but in general the fortunes of those who became wealthy here represented between 10,000 and 20,000 French pounds, which made it possible to enjoy a high standard of living on Bourbon island, but live only very modestly in mainland France.

Generally speaking, the fortunes of the settlers decreased during the 18th century. One of the main causes was the fall in the price of coffee brought in from Bourbon island. In August 1723, the Company was granted exclusive rights to sell coffee in France and announced that since “the object was becoming more and more considerable”, it would purchase the crop produced on the island at 10 sols per pound in weight15. However, this privilege was challenged for two reasons. First of all, the cargoes of coffee arriving in Marseille from Moka (Ile de France); in theory, the free zone was separated from the rest of the kingdom through a customs barrier, but the latter was not particularly effective and smuggling was widespread. The second obstacle was the development of coffee-growing in the Caribbean. The latter was adapted to the region as from 1721, despite the opposition of the directors of the Company, who had attempted to prevent plants from Moka being sent to the Americas. In June 1729, they received orders from the Secretary of State for Marine affairs for the intention of bursars in the Caribbean to have coffee growing forbidden, but the planters did not apply the ban, all the more so as their coffee was now very popular in the rest of Europe. In 1732, authorisation was given to store coffee originating in the American colonies and transiting through France; in 1736 permission was given to import it. Consequently, Bourbon coffee, which had to travel 2,600 leagues before arriving in France faced the competition of Caribbean coffee, travelling just 1,200. In addition, the Dutch started growing coffee in their colony of Java and the fruit of their production flooded the markets of northern Europe. As a result, in 1730 the Company lowered the purchasing price on Bourbon island to 8 sols per pound, 5 sols in 1732, 4 sols in 1744 and 3 sols in 1745. In that year, the company claimed to sell the product at 11 or 12 sols in mainland France, when the cost of freight amounted to 6 sols.

The income of the island’s settlers was impacted by this drop in prices. To add to this, the coffee plants were damaged by natural hazards, such as a cyclone in 1732 and aphids in 1747 and 1749, reducing the yields.

In addition, division of plots in French colonies between heirs, in application of the customary practice in Paris, led to a fragmentation of the land which was not conducive to maximum yields. Plots of great length divided up into one or two furrows became corridors impossible to develop.16 As a result, there appeared a large number of ‘petits blancs’ (small-scale white landowners): in 1735, one in 57 whites owned no slaves or one or two slaves, equivalent to living in poverty; in 1779, the proportion was one out of 10 whites living in this condition.

The increase in the number of persons living in poverty slowed down somewhat thanks to the development of agricultural production aimed at replenishing ships and their crews, a necessity that the Company regularly insisted on. In the 1720s and 1730s, these instructions were largely ignored. As was noted by a naval officer during a stopover on the island in 1734: “All that they are interested in is coffee. Consequently, it seems they have neglected their own well-being, when the ships arrive, since most of the inhabitants, focusing solely on coffee growing, are unable to provide the necessary food items, these having become more and more scarce.”17 La Bourdonnais, appointed governor of the island in 1735, decided to reverse this process, declaring: “almost in a pathetically to the population that the Company had settled the island with the sole aim of supplying food and water for its ships.”18 The population applied his instructions: at the end of his term of office, Bourbon island produced 5,500 quintals of wheat, 9,000 quintals of Rice and 40,000 quintals of maize. During the same period, the island’s Governing Council noted:

As long as the war (with Austria) lasted, the Ile de France (currently Mauritius) relied on us considerably for support in terms of cereals and would undoubtedly have been unable to supply the large amount needed by the vessels in its harbour, if it had not been able to find wheat and maize here…19

Most of the island’s needs were thus covered, but rice and salted beef still had to be imported from Madagascar.

In 1764, when the government considered placing the islands under the direct authority of the monarchy, the directors of the French East India Company assured them: “The islands cost their shareholders 50 million and the settlers owe their entire fortune to the Company.” It is true that the Company was giving the population financial support to enable them to buy slaves and begin working the land; the interests owed on these loans – repaid in the form of coffee – were naturally listed in the Company’s expenses. In addition, the Company kept 150 men as guards and policemen on the island and had committed itself to paying a salary to the civil administrators. These expenses were easily covered first of all by the earnings from the sale of slaves loaded onto the Company’s ships, as well as the sale of coffee in mainland France; also, in application of the decree dated 23rd April 1723, the Company would sell European (or Asian) goods to the settlers, making a profit of 100%, then 125% and 150% on the amounts invoiced, and for wine and brandy, the profit was 200% and 300%. This income applied the principle of the exclusive market and was the Company’s main source of income. To this was added the tax (in kind) of 4 ounces per acre of coffee, as well as transfer rights (approximately 15,000 French pounds). Consequently, the inhabitants of Bourbon island, after the initial investment, would cover their costs. It can even be considered that the island made a profit, if we consider the Company’s obligation to maintain a port of call along the East Asia route.

We can say that the development of Bourbon island under the East India Company represented a material and financial success. Commercial and financial balance was achieved, but this was at the expense of the settlers and the slaves.