Contrary to the process taking place in Europe, on Bourbon island persons working in commerce and trade played hardly any role in the setting up of industrial activity. Originally (1810-1817), they represented a very small proportion (5 %); the commercial capital was thus far from decisive. The exception was Denis de Kervéguen, a trader in Saint-Pierre who was initially a settler, then became a sugar-estate owner as from 1827 and who played a remarkable role.

Denis Marie Le Coat de Kervéguen, a young naval officer who arrived on the island from Brittany in 1796 was the first in the line. The son of impoverished low-level nobility, with no future considering the revolutionary context of the period, developed a prosperous business in Saint-Pierre based on a double strategy. First of all his marriages: the first with Angèle Césarine Rivière, who integrated him into the society of Bourbon and gave him a wealthy start: (6,000 pounds and 5 estates), the second to Geneviève Hortense Lenormand, a marriage which brought him connections with the bourgeoisie of Saint Pierre and consolidated his assets. However, he was not interested in income from agriculture. After developing some of his land, he opened a commercial establishment selling hats, cloth – notably Guinea indigo blue canvas, used in the manufacture of clothes for slaves – tools, wine, olive oil and spices that he brought in from Saint-Joseph. With the support of Joseph de la Poterie, he set up two mills at the mouth of la Rivière d’Abord and founded a bakery to provide bread for the town, the surrounding area and visiting ships. The British occupation of the island, which, like the Desbassayns, forced him to accept the invaders, had no negative effect on his activity. At the start of the 1820s, he decided to reinvest his commercial profits in land and started to plant sugar-cane. In 1827, he set up the first of the family’s sugar factories at Casernes and Terre-Rouge, thanks to water from the Saint-Etienne canal. At the time of his death that same year, his fortune represented over one million pounds, more than half of which consisted in debt obligations, and less than a third in slaves and real estate.

His eldest son, Gabriel, connected by marriage to the powerful Chaulmet family , first of all continued his father’s commercial activity.

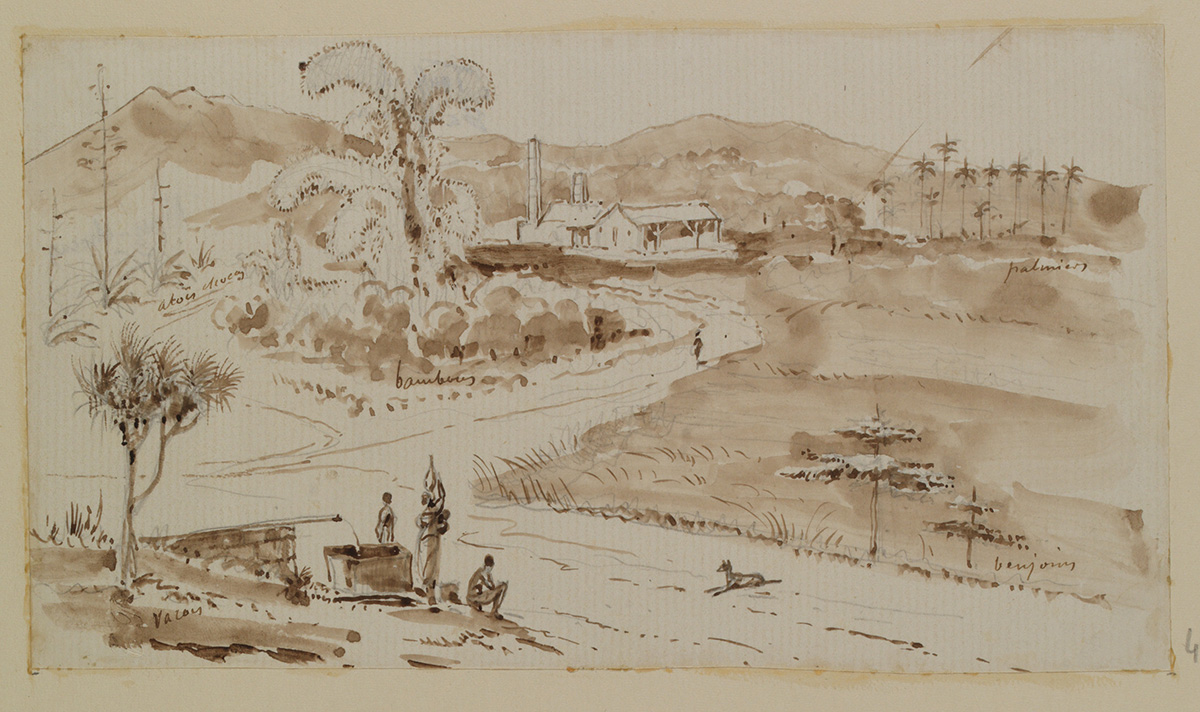

In 1829, with his brother Augustin, he developed an import-export activity, buying a first ship Le Renard. Others followed . Granted the concession of a ‘marina’ , the brothers traded throughout the Indian Ocean as far as China, as well as with mainland France. Gabriel had three other wharfs constructed, to directly supply his factories and warehouses in Saint‑Philippe, Manapany, Vincendo and Langevin. In the 1850s, he proposed to the governor Darricau a project for the construction of a harbour in Saint-Pierre. Coffee and sugar were exported to le Havre, Nantes and Bordeaux; as regards imports, he enjoyed a monopoly for cloth (taffetas, sheets, gauze, muslin and hats), as well as hardware, perfumes, saddlery and high-quality alcohols (champagne, whisky and beer). His ships were also loaded with rice in Madagascar, India and even Abyssinia. His products were stored in in a large warehouse overlooking the Rivière d’Abord in Saint-Pierre and others were construction in Saint-Joseph, Étang-Salé, Saint-Leu and Champ-Borne, with the largest in Saint-Denis.

However, Gabriel decided to mainly focus on sugar. Four years after the death of his father, the value of his land and its slaves rose from 33 % to 72 % of his assets. From 1828 to 1860, thanks to his many aquisitions, Gabriel de Kervéguen had built up a huge estate that rose from less than 100 ha in 1828 to 2,000 ha in 1840, 3,100 ha in 1848 and over 5,000 ha in 1860. His estates were mainly in the south of the island: 5,199 ha, or 92.8 % (2,895 ha in Saint-Pierre; 1,449 ha in Saint-Louis; 754 ha in Saint-Joseph; 101 ha in Saint-Philippe); much later, in 1852, he invested in the north east of the island in Quartier-Français (210 ha), then in the west in Saint-Leu in 1854 (Le Portail, 160 ha).

To the two sugar-estates inherited from his father, he added others. As a result, in 1836, he already owned six establishments. At the time of his death in 1860, the marriage contract of his daughter Emma

with Napoléon Mortier de Trévise , states that he owned 13 estates, a number mentioned by the song-writer Célimène :

“Monsieur de Kervéguen / n’est pas riche en vain / il a beaucoup de noirs / et treize établissements”

(Mr de Kerveguen / is not rich in vain / he owns many Blacks / and thirteen estates).

There were ten factories and three distilleries. The heart was in Saint-Pierre: the factory of Casernes, on a slope above the town, inherited from his father, was the island’s most prosperous, with the capacity to produce 1,000 tonnes of sugar, on the road leading to Le Tampon, the factory of Mon Caprice (800 t), the one in Le Petit Tampon (500 t; bought from the Hoareau brothers in 1837),

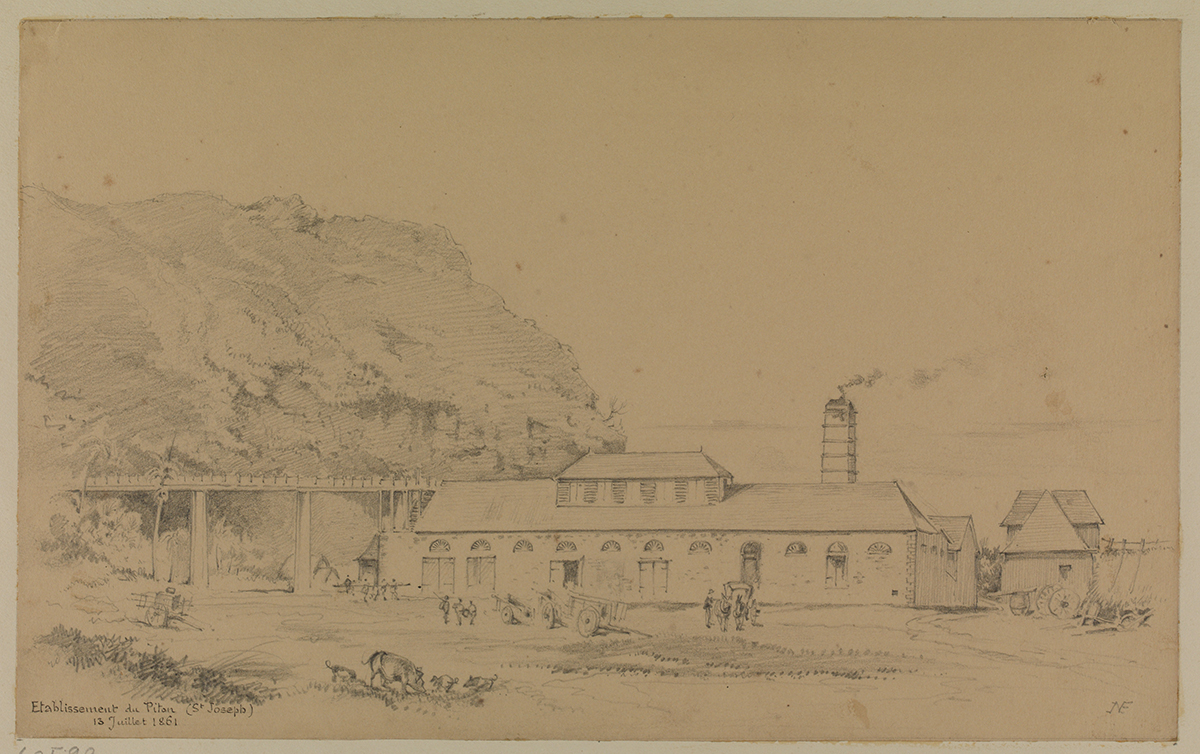

Entre-Deux (400 t: described in Roussin’s Album under the name of Etablissement de La Rivière), in Saint-Joseph, le Piton, at the foot of the Piton Babet (1854, 300 t),

Langevin (1839 ; 500 t) and Vincendo (purchased in 1852 with Montbel-Fontaine, 500 t). Finally in Saint-Louis, the factory of La Chapelle, or Les Cocos (purchased from his brother in 1847: 700 t), then the one at Etang-Salé (300 t, taken over form his father-in-law André Chaulmet in 1841) and finally in the north east, a factory in Quartier-Français, set up as from 1852 (800 t). As for the three distilleries, these were located in Casernes (150,000 litres), Etang-Salé (100 000 litres) and Quartier-Français (100,000 litres).

All these factories made Gabriel de Kervéguen the colony’s most important employer. Until 1848, he employed 1,538 slaves, the greatest number being in Saint-Joseph with 41.6 % and Saint-Pierre with 41.4 %, as well as Saint-Louis (9.5%) and Saint-Philippe (7.5 %). Most of these were men (73%), which was the general trend. It was also multi-ethnic, for economic reasons (each ethnic group was thought to have specific skills), as well as political (avoiding tensions and rebellions, limiting solidarity between the groups that had difficulty communicating and did not always get on). In 1830, the dominant group owned by the landowner was that of Africans (57 %), then Madagascans (33 %) and Creoles, more acculturated (8,5 %); there were few Indians (1,5 %). In 1847, there were more Creoles (50.7 %) than Africans (34 %), Madagascans (13,5 %) and Indians (2 %). A minority of the Africans acquired professional skills: to the ‘professional’ slaves, who constructed the factories, were added ‘technical slaves’ producing the sugar as well as working and taking care of the upkeep of the machines (30 %). However, the majority (70 %) consisted of “Noirs de pioche” (labourers).

These slaves were housed two or three to a small hut. In 1841, for 81 slaves are mentioned “30 slave huts with leaf roofs, in poor condition”, built of straw, and above all timber, more rarely stone, sometimes scattered around the estate, but mainly grouped close to the house in the “slave camp”. They were as badly treated by Kervéguen, openly anti-abolitionist, as by the other masters. In 1848 on the estates of Saint-Pierre, there were 4 % of maroon slaves (fugitives), above all “short-term” . At Le Tampon (over 200 slaves) a total of 26 offences were registered: 7 cases of maroonage (escaped slaves), punished by 15 days imprisonment, punishment that, according to Kervéguen, the Blacks made fun of: “Since the ordinance that was passed [1845: the “Mackau law”], he wrote, the Blacks … see the 15 days in prison as a period of rest and often deliberately bring on the pleasure”: 2 cases of insubordination in front of the steward or foreman (15 days in prison); 4 cases of absenteeism or refusal to work (15 or 10 days in prison); there were also 13 cases of theft of goats, rabbits and tortoises, “chickens”, rice, green coffee, sugar and sirop, also punished by 15 days in prison. Acts of resistance, (52 %), went hand-in-hand with thefts, to compensate for a shortage of food or obtain money from buyers of stolen goods (48 %). The hard work, the brutality of the environment, abject poverty and mechanical application of sentences led to the population deserting the factories in huge numbers following emancipation in 1848. Of the 3,203 indentured labourers (1857) only 249 had been emancipated in 1848 (7.8 %), to whom can be added a few domestic workers close to the family.

His refusal of abolition, which he often expressed before the Constitutional Council, did not prevent him from taking advantage of emancipation. Having sufficient assets, before the actual payment of the compensation (1852), he bought up a large number of compensation coupons below their true value from small landowners who were glad to be able to reduce their losses. Declaring only 1,538 slaves, he exchanged coupons for 10,000!

After 1848, he became the island’s most important employer of indentured labourers: in 1857, he employed 3,203. Africans (30 %), Indians (23 %) and Madagascans (23 %), proportions that nevertheless varied from estate to estate. Their accommodation changed: considered to be cultural outsiders, the indentured workers were housed in collective huts, systematically grouped together in camps set further away from the ‘Large Mansion’. Living and working conditions were hardly different from those during slavery. They worked 11 hours per day, with less than two hours for meals. Every Sunday, they were given regulatory rice, cod, salt and pulses and received two changes of clothing per year. When necessary, they received medical care from doctors (de Lissègues and de Mahy) and their meagre salary was paid out every two months.

The question of salaries led Kervéguen to carry out an operation characteristic of the colonial universe. The indentured labourers, considered to be sober, hard-working and carful with their money, were distrustful of paper money and preferred to be paid in hard cash, which the employer accepted with the aim of encouraging them to renew their contracts. However, coins were in short supply on the island. Kervéguen came up with the idea of importing a stock of Austrian coins of 20 kreuzers (zwanziger), recently devalued, to pay the salaries. In 1859, with the approval of the authorities, 227,000 coins were brought in.

The operation was so profitable that hundreds of thousands of kreutzers started to circulate fraudulently over the island. 20 years after the death of Gabriel, when the government of the 3rd Republic decided to withdraw all foreign currency circulating in the colonies (1879), the population lost confidence in these coins, estimated at 800,000 in number, resulting in users and shopkeepers becoming bankrupt and destitute. Following a long trial, his son Denis-André was forced to commit himself to paying back the value of the 227,000 coins initially brought in.

Throughout his life, Gabriel de Kervéguen remained highly circumspect as regards public life, refraining from attachment to any specific political regime, refusing honours and decorations, including the Legion of Honour. His only honour was the title of “Roman count”, purchased from the Vatican, as well as the construction of a splendid mansion at Les Casernes.

In the middle of the garden, a green arbour and screen separating the family from the sugar factory and the workers’ camp, two houses, each with an upper floor, were linked up by a closed three-windowed veranda, used as a reception room. This opened out onto the office of the sugar-producer, onto another veranda turned towards the ‘mountain winds’, and the large three-windowed dining room. The decoration of the pediment, the layout of the mansion with its vast esplanade, its location facing the harbour where the ships that were behind the success of the family could be seen sailing in, reflected the rich factory-owner’s desire to impress.

Gabriel de Kervéguen died in a carriage accident in Paris on 4th March 1860; he is buried in the Père Lachaise cemetery.

He is an example of the transition from classic agriculture to agriculture producing maximum profit. He applied the change from planter to capitalist entrepreneur. Sugar and sugar-cane were no longer simply grown on the land, but were based on wealth.

Denis-André Le Coat de Kervéguen (1833-1908), his eldest son, having lost his mother at a very early age, was raised by the family’s servants at Casernes and was beloved of his aunts, including the painter Adèle Ferrand, wife of his uncle Denis‑François.

After a short period studying at the Collège Royal in Saint-Denis, his father, wishing to preserve the family’s fortune, associated him in the family’s business through a limited partnership. After his father’s death, he decided to modernise the family’s industrial heritage, associating his brother-in-law Hippolyte Mortier (1835-1892) in the company Société Le Coat‑Trévise. The company sold off the less profitable establishments (Piton Rouge and Etang Salé) and with the fruits of the sales invested in new machines. The company’s flagship factory was the one in Quartier Français, reconstructed from 1870.

Equipped with triple-process boilers, a grinder, filters to purify the massecuite, it led to the closure of neighbouring establishments. Managed by reliable men more or less related to the family, the factories manufactured products (sugar and rum) that received awards at universal exhibitions such as that of 1867. At the end of the century, Denis-André de Kervéguen sold several of his plots of land (in Le Tampon and Saint-Pierre). The island went through a serious economic crisis, intensified by the sums of money owed to the Crédit Foncier Colonial. Kervéguen attempted to compensate for these difficulties by investing in New Caledonia, at the request of the governor Guillain, former commander of the Naval base of Bourbon (1836-1839). However, the company Ouaménie-Le Coat, founded with the Reunionese Nas de Tourris, only survived for twenty years or so. Unlike his father, Denis-André often travelled to mainland France, where he married the sister of François de Mahy at the château d’Escoire (Dordogne). His children were born in his house in the Faubourg Saint Honoré. Though he maintained close contact with his businesses in Reunion, and despite several periods sitting on the island’s General Council, he began to organise the return to mainland France of a family that had become rich thanks to the native land of his ancestors. He died in Paris in February 1908, after associating his son Robert in his business, again through a limited partnership.

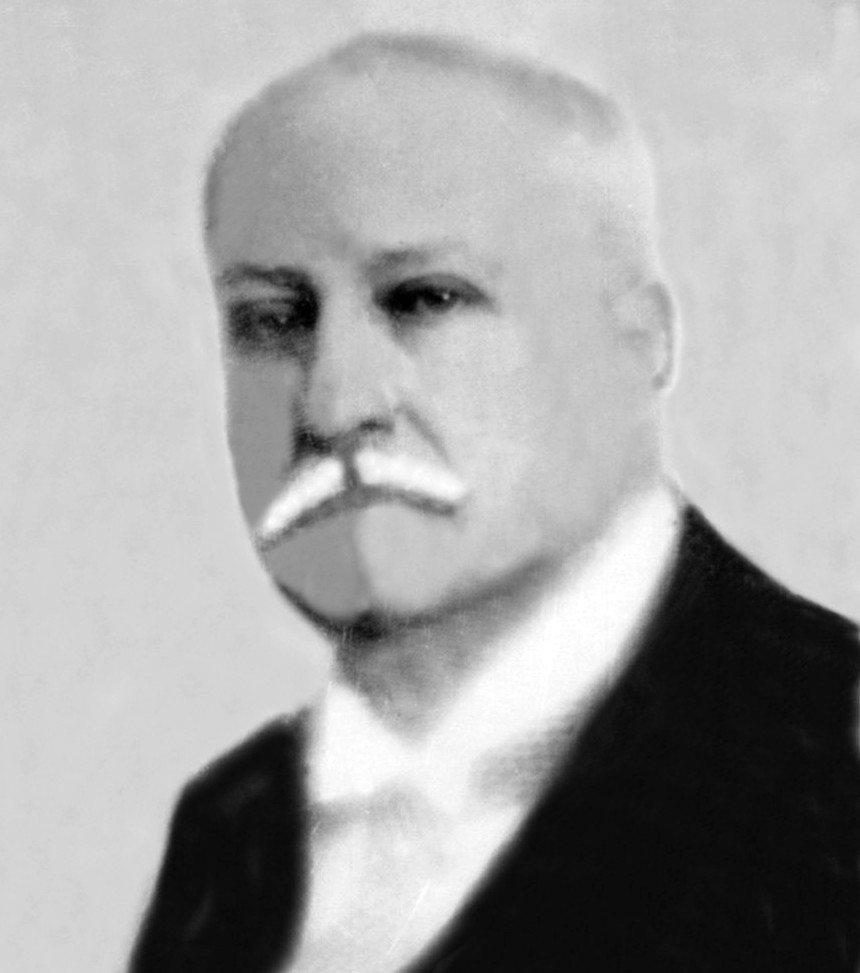

Born in Paris in September 1875, Robert Le Coat de Kervéguen was the second son of Denis-André Le Coat de Kervéguen and Adèle de Mahy, François de Mahy’s sister .

After attending the Collège Stanislas, Robert studied medicine, while participating in escapades along with other dandies of the Reunionese diaspora. Back in Reunion, he practised medicine at the thermal baths in Salazie, but did not open his own surgery. After the death of his father, through a new limited company, created by him, a relation of his brother-in-law (Rochechouart-Mortemart) and his aunt Emma, Mortier’s widow, he took charge of the family business, modernising (process of crushing the massecuite, installation of Weston hydraulic turbines) and rationalising the industrial equipment. The factory in Le Tampon was closed down (1902). Investments were concentrated on the establishments of Casernes (which centralised the sugar-cane from the estates of Le Tampon), Quartier Français (destroyed by a fire 1899, immediately reconstructed and equipped with American installations) and Le Gol (of which the purchase in 1902 resulted in heavy debts for the company). Having become, with the Crédit Foncier Colonial, the island’s main producer and industrialist, he was appointed chairman of the union of sugar producers in 1908. The activity was interspersed with events judged to be scandalous by the Creole society of the time, notably Robert’s liaison with the actress Mlle Deverne, for whom he purchased the ‘chateau’ of Bel Air (Le Tampon) before marrying Augustine de Villèle (1917).

There was also a long struggle, with alternating virulent criticisms, petty mean actions and reprimands, led by Father Rognard, revolted by the destitute nature of Kervéguen’s settlers.

Like many company directors, foreseeing the assisted nature of the population following the abolition of slavery, Robert de Kervéguen decided to go into politics. He defended the interests of the sugar-producers before the Doumergue government, was member of a delegation at the permanent sugar commission (Brussels), aimed at securing their representation; from 1903, he was member of the French Colonial Union. In 1914, he stood as conservative candidate at the legislative elections against Georges Boussenot, counting on the votes of his dependents, workers and settlers. After a particularly violent electoral campaign, Kervéguen, representing a truly conservative vision of a Reunionese society immobilised through ignorance and submission to those in power, lost the election. On March 20th 1920, for reasons more or less unclear – failure in politics, family issues, fear of harmful land reform, international uncertainty regarding the future of the colonies, opportunity to take advantage of a peak in sugar prices – he sold all of the family’s assets in Reunion to the company Société Foncière Maurice-Réunion Limited, though retaining only part of the fruits of the sale. In addition, the debts of Le Gol were not entirely paid off. We have the impression of a mismatch with the realities of the island, as well as a certain weariness. Returning to mainland France, Robert de Kervéguen bought the château of de Vigny (French Vexin) and died in Paris in April 1934.

In the society of Bourbon during the life of the first two Kervéguen, the absence of titles and noble ancestors left the way open solely to money. Ultimately, money could be associated with speculation, if, through personal ambition as from the 1820s and 30s, there had not also been the desire to place more and more importance on extending the company.

After them, Robert de Kervéguen only saw money as being a facilitator, not as a symbol of position in the society. Personal income made it possible to be well considered in the society, to assert one’s rank, furthering one’s career. However, the era of all-powerful sugar planters came to an end in the 1880s. The logic of universal suffrage, made invisible through the paternalism and assistance that reigned in Reunion at the time, intensified by legislation through the unions, led to the emergence of a new generation of political and union leaders (Gasparin, Boussenot), whose objective was to improve the conditions and income of the island’s workers. The profit margins of the sugar producers decreased in accordance.

The feeling that the war, in some way, contributed to putting an end to the prosperity and security of the bourgeoisie, henceforth scattered over the island, also explains his departure, soon to go hand in hand with his fading from people’s memories.