In 1830, following a period of growth in sugar production, characterised by the expansion of the amount of land devoted to sugar cane and an increase in the number of refineries, the economy of Bourbon Island went through a period of crisis. This was due to several factors, mainly commercial and industrial. Facing competition from beet sugar, but also subject to heavy taxes, the local refinery owners could no longer sell their sugar at a high price. In addition, the quality of the product deteriorated. The reason was the extension of sugar as a crop, which was planted on plots not at all appropriate to sugar cane, leading to a decrease in yields, which altered the quality of the sugar-cane juice. The latter had become extremely heterogeneous and increasingly difficult to transform, resulting in a product that often became altered during shipment to mainland France.

Many refinery owners, having accumulated debts due to the policy of land purchase and the expense of improvements made to their workshops, and, in addition, their sugar-cane plantations damaged by the 1829 cyclone, were forced to declare bankruptcy. One consequence of the crisis was that refinery owners became aware of the need to question their industrial practices.

Some of the wealthier owners decided to invest in the latest sugar production technology, importing techniques developed for the manufacture of beet sugar by refineries in mainland France. The other solution, which may seem contradictory, but which was in fact complementary, consisted in adopting processes and equipment developed by Joseph Martial Wetzell, an engineer who was a graduate of the prestigious French Ecole Poltechnique, brought in from mainland France by the General Council of Reunion. Rather than using the latest technologies, which would turn out expensive, he aimed to solve production problems by increasing yields and producing sugar of a higher quality through improving local equipment, as well as adopting manufacturing processes and equipment adapted to local conditions. His focus was on economy, simplicity, reliability and efficiency.

On arriving in Bourbon island in 1830, Wetzell decided that each district on the island should be equipped with a ‘model’ sugar refinery, to serve as an example for sugar producers wishing to modernise their refineries. On 11th March 1831, the General Council issued a bulletin addressing all the town councils, enjoining them to select a refinery which was ‘to be a model’. The refinery concerned was to be constructed at ‘a central point’ of each district, to facilitate visits by refinery owners.

The refinery belonging to the widow of Panon-Desbassayns was ‘quite naturally’ selected by the town council of Saint Paul as one of these model establishments. The reputation and the role played by the Desbassayns family (notably Joseph and Charles) in the early years of the development of sugar-cane as a crop on the island, as well as that of the sugar industry, the family’s wealth (modifications to a refinery and carrying out experiments cost money), the location of the refinery, more or less situated centrally in the sugar-growing area of west of the island, as well as its ease of access by road, were criteria that certainly contributed to the Desbassayns refinery being selected. From then on, the refinery became one of the major centres of technical progress for the sugar industry on Bourbon island.

Wetzell’s work in Saint-Gilles-les-Hauts was carried out in two stages:

– the first stage consisted in general improvements made to the functioning of the sugar refinery, which he carried out in the early 1830s in response to the urgent needs of refinery owners;

– the second stage, during which new sugar refinery equipment was developed, took place following the end of the 1830s.

The first tasks carried out by Wetzell in the Saint-Gilles processing plant were aimed at improving the efficiency of processing the sugar-cane juice in order to produce higher quality sugar. The extension of the sugar-cane crop to areas which were not always appropriate had resulted in important fluctuations as regards the quality of the juice, leading to mediocre products coming out of the processing plants.

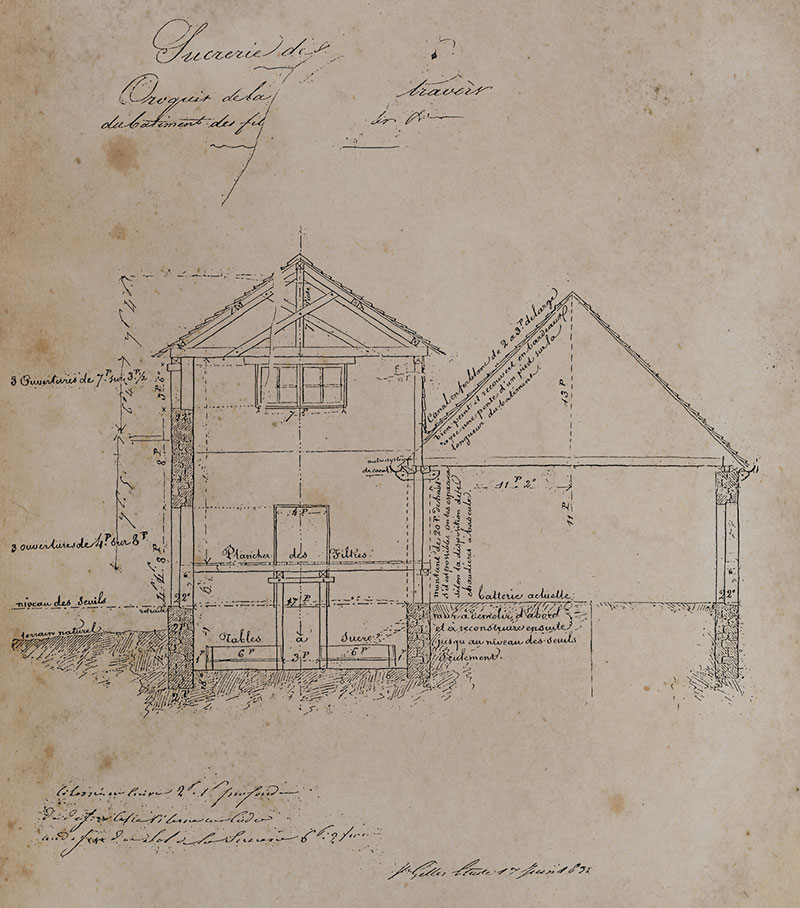

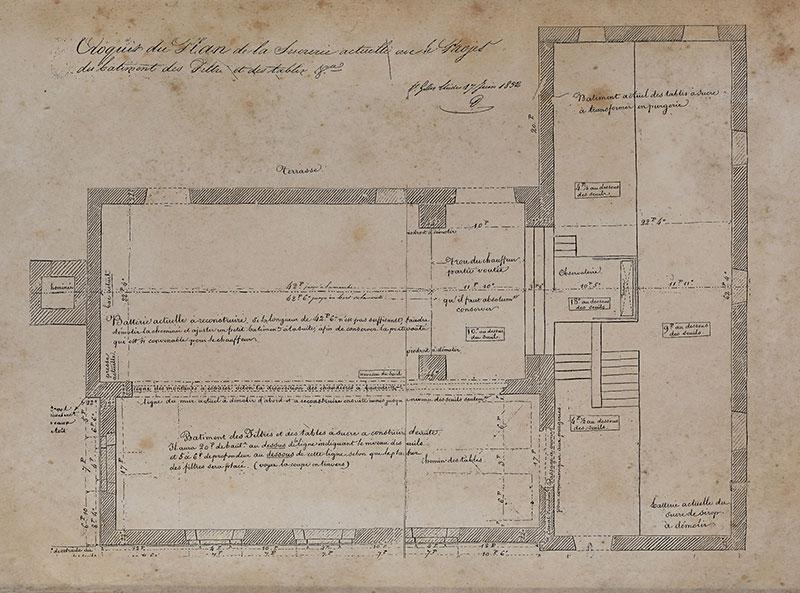

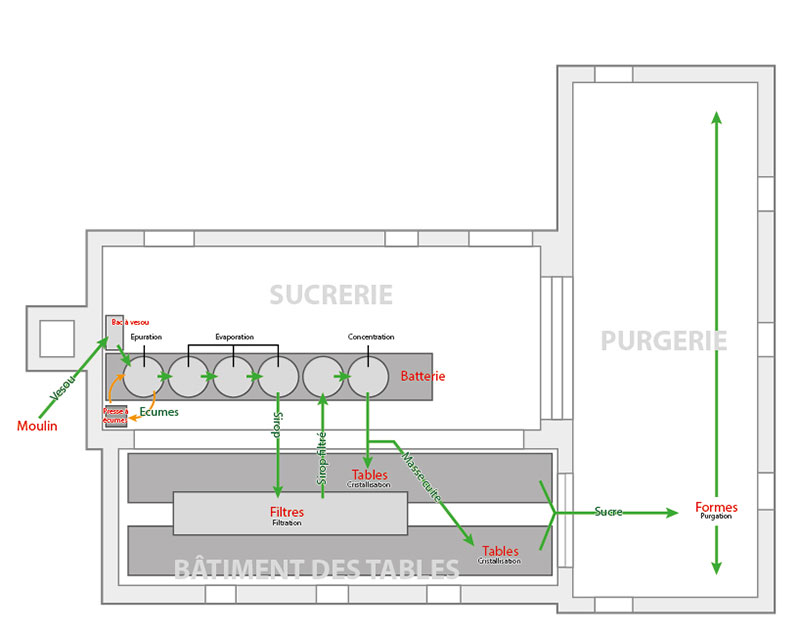

As from the end of March 1831, the engineer’s analysis focused more particularly on modifications to be carried out concerning the boiling house, a central element of the refinery where the sugar-cane juices were processed, after which his attention was turned to the repercussions of these modifications on the organisation and general functioning of the refinery, while at the same time for economic reasons limiting any alterations made to the architecture of the refinery. A diagram of the alterations made to the refinery in 1832 gives an idea of the work carried out by Wetzell.

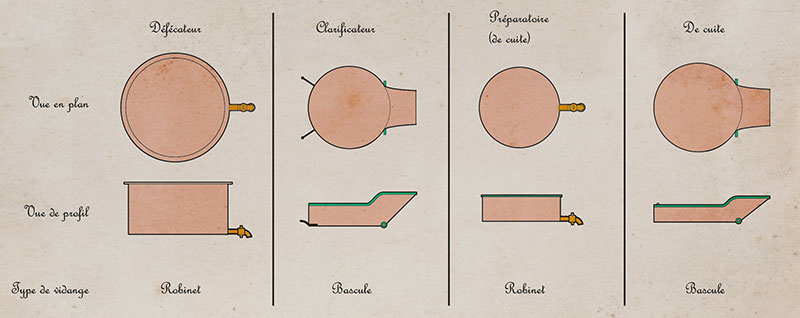

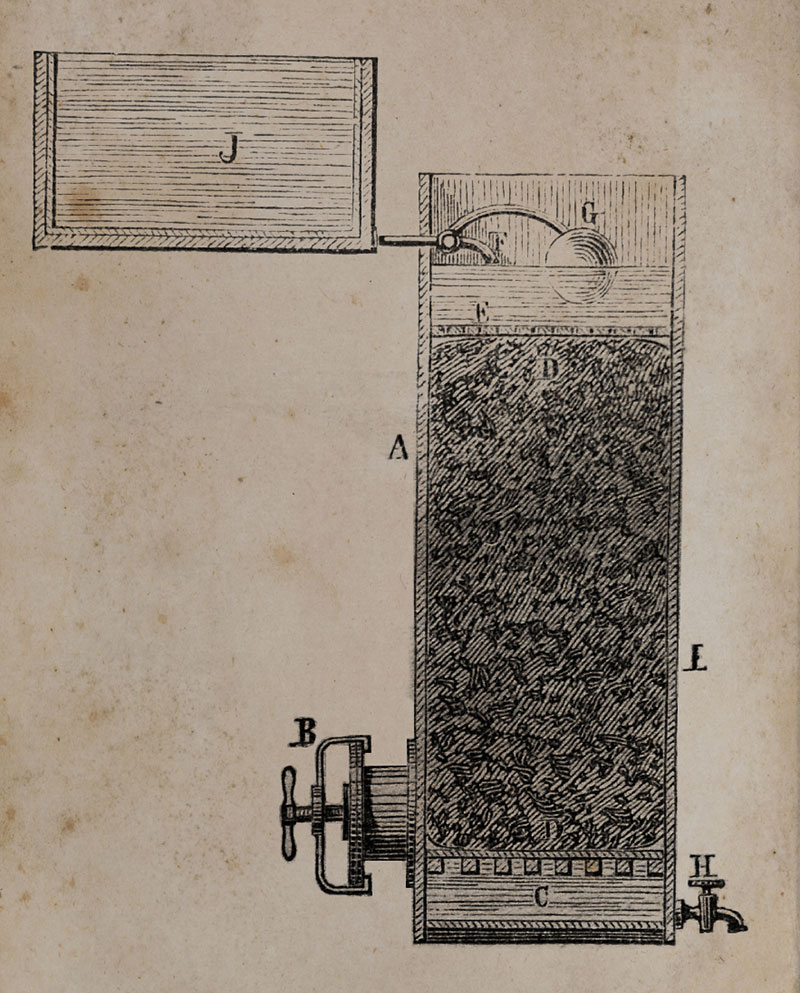

The engineer had a new boiling-house installed, consisting of six boiling pans (evaporating pans), with the aim of improving the clarification process, setting up a linear structure for operations (the latter had previously been interrupted through the existence of a second boiling-house, in another building, dedicated solely to syrups), as well as reducing the number of men needed to run the refinery, in a context of workforce becoming difficult to come by. To carry this out, the engineer installed swivel pans he had already experimented with at le Chaudron (Saint-Denis), equipped with taps and a pump to decant the juice, thus accelerating and facilitating transfer between pans. A skimming press, installed close to the boiling pans made it possible to extract from the latter any sugar-cane juice potentially convertible to sugar. Filters were also installed in the building which housed the ‘tables’ or coolers that he had constructed immediately parallel to the sugar refinery, thus shortening the distance between the boiling pans and the filters.

The Desbassayns refinery revolutionised standards and introduced technical innovations and, like the refinery in le Chaudron, was one of the first sugar refineries to apply a process usually reserved for sugar beet: the technique of filtering, a process which, up until then, had never been used on Bourbon island. At right angles to the refinery building and the new coolers, the building formerly containing the coolers, now cleared of the latter and the boiling pans for the syrups, was converted into the clarification room, where the rectangular-shaped moulds were stocked, also a novelty in comparison with the moulds previously used in the sugar industry.

It is thus possible to follow the new manufacturing process set up by Wetzell following the first stage of his work:

The sugar cane was transported in carts to be crushed at the refinery. The sugar-cane juice (vesou) obtained was pumped out to the refinery, where it was poured into a storage-pan, where a portion of the waste resulting from the crushing was retained. The juice was pumped into the first boiling pan, to undergo purification: using lime and heat, the juice underwent the operation of clarification (also referred to as defecation). The coagulated waste matter forming the scum was skimmed off and crushed using the skimming press. The purified juice was then transferred to three fixed evaporating pans: the water was evaporated to form a syrup, which was then transferred into the fifth evaporating pan (referred to as the ‘syrup’). The syrup was then put through Dumont filters, to retain the fine particles and to be bleached (clarified). The syrup was now ready to be concentrated. By means of the juice-pump, it was transferred into the evaporating pan, to be heated until it reached the point of crystallisation, monitored using a ‘sieve’. At this stage, the sugar was transferred into the ‘tables’ or coolers, where it was spread out and cooled in the large shallow vessels, enabling crystals to form. Once formed, the damp sugar was placed in moulds in the clarification room, in order to remove its syrup, which was sent back to go through the production process once more After three weeks of ‘moulding’, the sugar, purified of most of its water content, was set out to dry on slabs in the sun, either on a patio placed on the ground, or on a roof. Once dry, the sugar was packed, ready to be transported.

Without abandoning the process making it possible to manufacture better quality sugar, Wetzell continued his work, designing an apparatus that would enable refinery owners to increase the amount of sugar produced. The weak point in the system up to now was the fact that during the very delicate process of distillation of the syrup, a portion of the sugar could not be crystallised and was lost in the molasses.

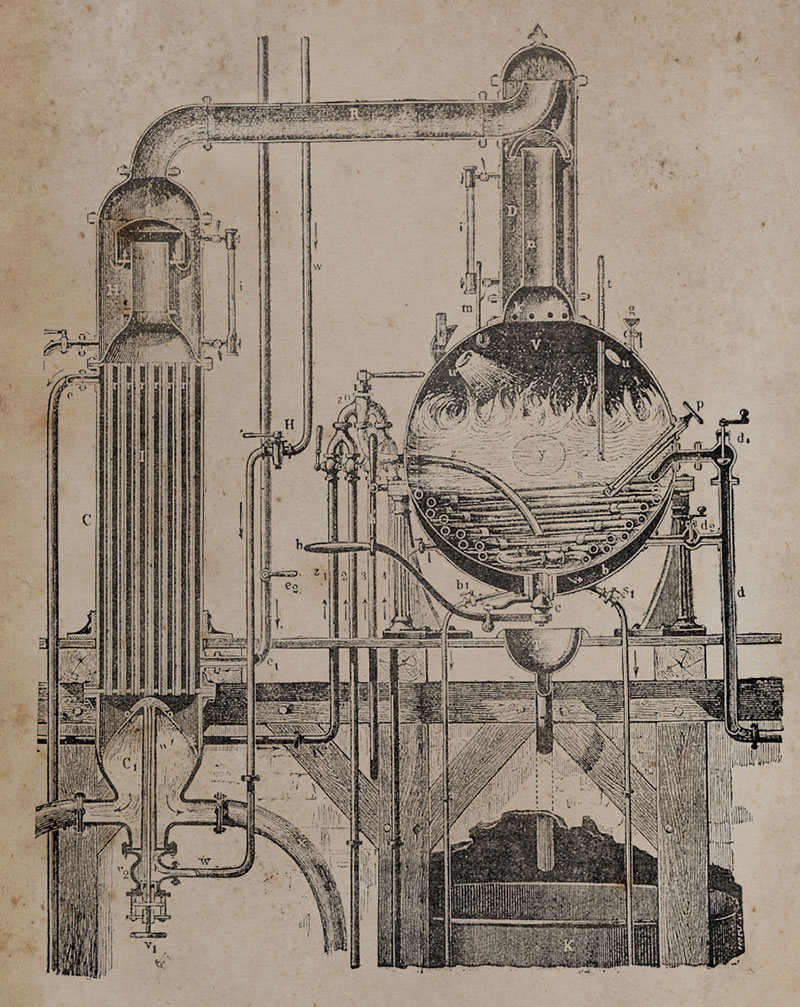

To solve this problem, the local sugar manufacturers could now make use of an apparatus which had, up till then, been used in the sugar-beet industry: an evaporating pan for distilling in a vacuum, which made it possible to control this crucial stage in the manufacture of sugar. However, not all the refinery owners could afford this this technology, adopted more or less successfully by a handful of wealthy industrialists.

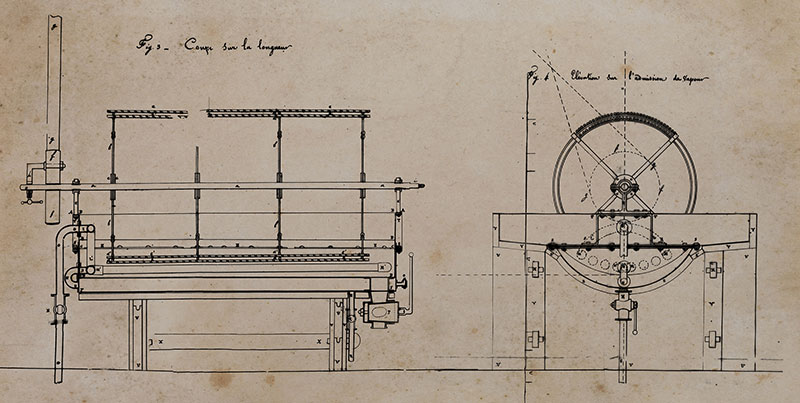

From 1834, Wetzell began to consider the possibility of finding a technique to produce evaporation at the lowest possible temperature, in order to avoid risk of caramelization. The latter tended to occur when the sugar-cane juice was not perfectly pure. It was Wetzell himself who achieved his objective with the development of the famous ‘low-temperature evaporating pans’, referred to in notarial deeds, as well as in technical or general literature, as ‘Wetzell evaporating pans’, ‘Wetzells’ or ‘rotators’: the process of achieving evaporation at a low temperature, developed with the close support of the Desbassayns family, from then on became the technique used locally as an alternative to the vacuum process, generally used outside the island. These evaporating pans, of different shapes, were considerably successful with local refinery owners during the second half of the 19th century. Costing a quarter of the price of vacuum pans, tough, efficient and easy to maintain, they quickly became popular on the island: between 1851 and 1860, 96% of the sugar refineries on Bourbon Island had at least one apparatus of this type. Over 90% of them were still in use for heating sugar-cane syrup in 1870.

With these systems, later perfected by Wetzell and his successors, the engineer produced an industrial model which partly turned its back on former mechanisation but fulfilled the needs of the refinery owners: “He implemented a simplified technology, giving us a glimpse of the capitalistic weaknesses of the sugar producers. There was no increase in the number of slaves to be used, the workforce becoming less easily available during this period, and more complex tasks were not demanded of them, since their level of qualification, though real, remained low. However, the progress made was considerable and, by 1835, 42 sugar refineries had adopted this process,” notes Jean-François Giraud in one of his texts. The refinery of Saint-Gilles, location and vector of these improvements, perfectly fulfilled its role of model establishment, its influence even going beyond the territory of the island: now manufactured by mechanical construction companies in mainland France, Wetzell apparatuses could be found installed throughout the south west Indian Ocean (Mauritius, Madagascar, Nossi-Bé and Comoros), but also in the Caribbean sugar producing region, in the French West Indies, in Brazil, as well as in the province of Wellesley, Malacca.