After a period as a trainee sailor for the French Navy in India, Desforges Boucher (1671/1680 – 1725) was employed as a clerk by the governor of Pondicherry, then by the French East India Company. Thanks to his qualities and skills, he occupied the post of warehouse keeper on Bourbon island between 1702 and 1709 under the authority of the governor De Villiers. Achieving the status of deputy for Beauvollier de Courchant, he was given the important responsibility of developing coffee, producing the precious crop of which consumption in mainland France had greatly increased. To this aim, the Company granted concessions or gave sums of money to all those, civil servants, employees of the Company or simple residents, wishing to work the land.

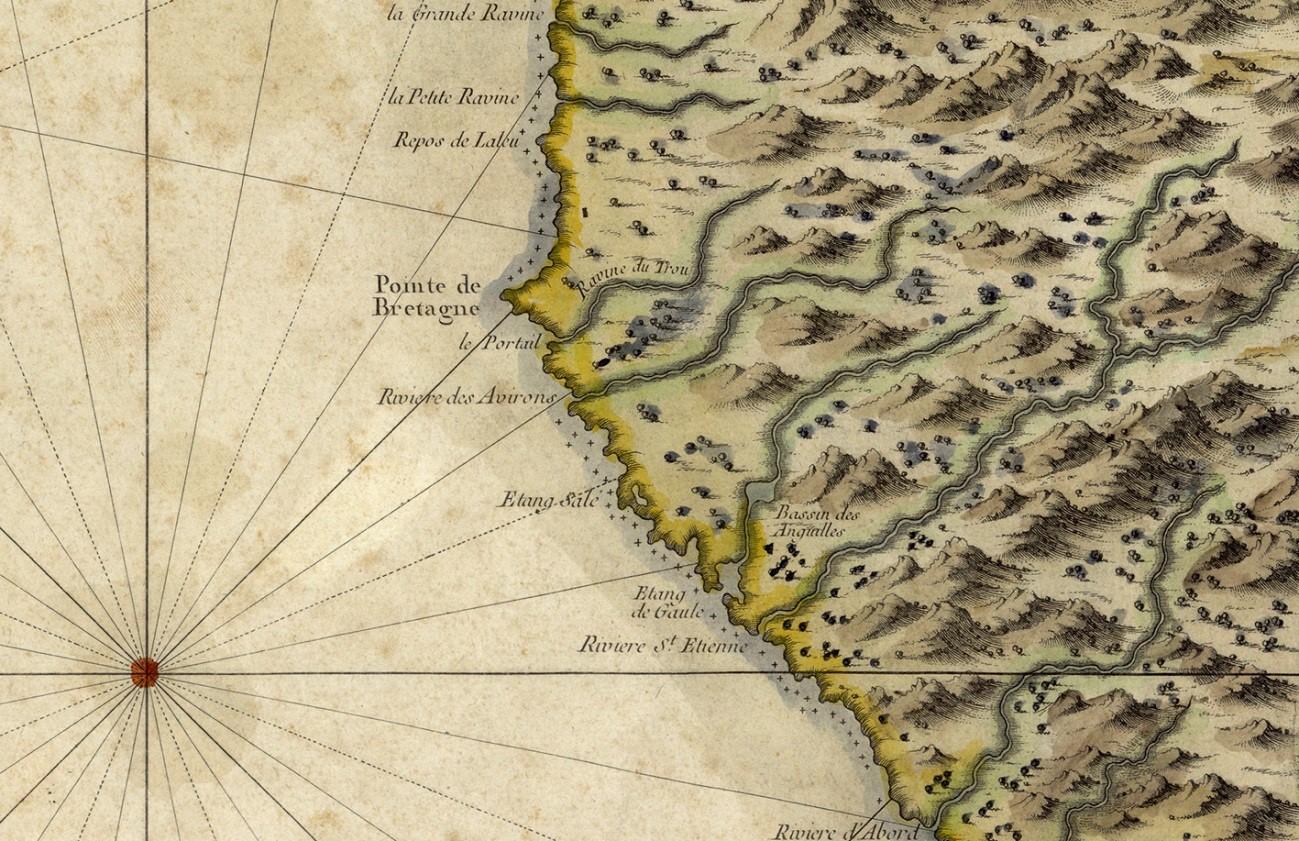

Desforges Boucher was the first to be granted concessions of land in this area. He was also granted a considerable estate of over 1806 hectares between la Ravine des Cafres and la Ravine du Gol in Saint Louis, part of which he planted with coffee. The plots of fallow land were now beginning to be planted thanks to slave labour on the estate established by Desforges Boucher.

Coffee was not, however, the only crop grown on the estate. Food crops and animal husbandry were also developed, by necessity, each year Boucher having to hand over to the East India Company a hundred pounds of white rice and two sheep, as well as taxes paid on the “fruits and products” grown on the estate. This shows that, contrary to common belief, production on the island’s estates was not based on monoculture. In 1725, Desforges Boucher obtained the estate of Maison-Rouge which had been granted to Sicre de Fontbrune a few years previously, the latter having been unable to develop it.

The death of Desforges Boucher, occurring in the same year, lead to the division of his estate between his four children and in particular his two sons Marie-Antoine (1715-1790) and Jacques Desforges Boucher. Jacques administered the property while his brother Marie-Antoine decided to embark on a military career.

Only a very small section of the estate which had been cleared (4,26%) was really developed at the time, even though a large number of slaves (174) were employed there. The estate, divided up into two parts “the lower estate” and “the upper estate” was planted with 16,000 coffee bushes. The remaining areas of the arable land were used for food crops (rice, wheat etc.). Agricultural work was difficult. Very few tools were available and the ones that were were very basic. Le Gol only had one millstone for grinding grain, a five-mortar pestle for coffee, seven axes, six picks, one frame-saw, one hand-saw, two iron cramps, one auger and a pair of pliers. Due to the large number of slaves living there, the estate was the most densely populated geographic area of Saint-Louis.

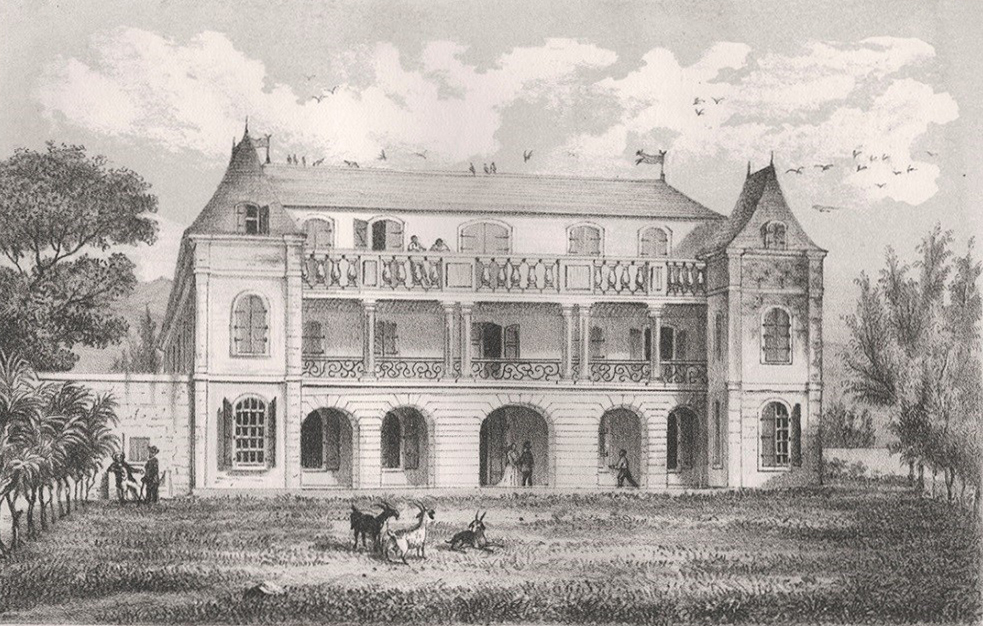

Having joined the company of the King’s engineers in 1740, Marie Antoine Desforges Boucher returned to Bourbon island to occupy the post of chief engineer. Financially well off, he was politically powerful. To reflect his success, he had a very grand mansion constructed in 1747, immortalised by Antoine Roussin in one of his lithographs.

In 1755, Jacques sold his share to his brother Marie-Antoine. After acting as governor by interim in the absence of Bouvet de Lozier in 1757, Marie Antoine was governor of the Ile de France (today Mauritius) from 1761 to 1766. He took charge of the administration of Bourbon island in 1767. Following a very busy period working in administration and after making a certain profit from his business, Marie-Antoine Desforges Boucher decided to leave Bourbon Island in 1783 to settle in Lorient, where he considered life would probably be more exciting. The following year, the estate was sold to two rich inhabitants of Bourbon island, Joseph Jean-Baptiste de Lestrac (ca. 1736-1814) and Antoine François Marie Pascalis, who was Mayor of Saint-Louis in 1791.

The estate developed, with 206 slaves now working there and there was also a herd of “200 horned beasts, 100 sheep and 50 pigs.” This opulence contrasted with the rest of the area, described as being one of the poorest in the colony. In order to acquire undivided ownership of the estate, Pascalis had needed to take out a loan from Mr Jean-Valfroy Deheaulme (1748−1819) and Mr De Saint-Aubin. The situation at the end of the 18th century is not clear and during this period, unfavourable for business and troubled by the events of the revolution, the first division of the estate took place.

Probably unable to pay off the instalments on his loan, Joseph Jean-Baptiste de Lestrac sold his half of the estate to his creditor Pierre de Saint-Aubin, a rich landowner and negotiator who also had business interests on Bourbon’s sister island (an indigo production plant and a sugar refinery at Petite Rivière).

The latter left the estate to his heirs in 1795, who in their turn sold it in 1799 to Mauritian dignitaries (landowners and negotiators), Jean-Baptiste (1797-1879), Antoine (1802-1863) and Philippe (1786-1853) Couve. The other half, still in undivided ownership, remained the property of Antoine-François Marie Pascalis. In 1801, the two large sections of the estate were separated, putting an end to the undivided ownership: preferring the southern part, now referred to as the “upper estate”, the Couve brothers acquired a little over one half of the land (16/30) with 148 slaves: this section later became the estate of Le Gol as such. Pascalis acquired the northern section, now referred to as the “lower estate”, where the former mansion of the Boucher family had been constructed: part of this section became the estate of ‘Le Château’. Pascalis, who was living in Le Gol, obtained permission from the Couve brothers to administer the estate in its entirety. At the time, it did not yet have a sugar factory.

In 1817, two of the Couve brothers, dissatisfied with the way in which the accounts were managed by Pascalis, decided to sell their shares to Auguste Blaise de Maisonneuve, Henry Marie Salaün de Kerbalanec and to their brother Jean-Baptiste Couve de Murville. As regards the estate of Le Château, this is also underwent changes. Ownership was transferred to the heirs of Pascalis but, since they had not respected repayment of a loan contracted by their father, they were forced to sell it to Jean−Valfroy Deheaulme. The start of sugar production on the plateau of Le Gol dates back to this period.

The wars of the French Revolution and the Empire that took place between the late 18th and the early 19th centuries disturbed relations between mainland France and its colonies. In this wider context, France lost two of its main sugar producing islands. While the colonial power lost Saint-Domingo in 1806 following a rebellion by it slaves, the former Île de France was conquered by the British in 1810. The end of the wars and the return of Bourbon island to France in 1815 formed the backdrop to Bourbon’s sugar production. The island, where for a long time activity had been limited to agriculture, in a very short lapse of time took on an industrial role. From then on, the island experienced a true boom regarding its sugar production, which also concerned the owners of Le Gol.

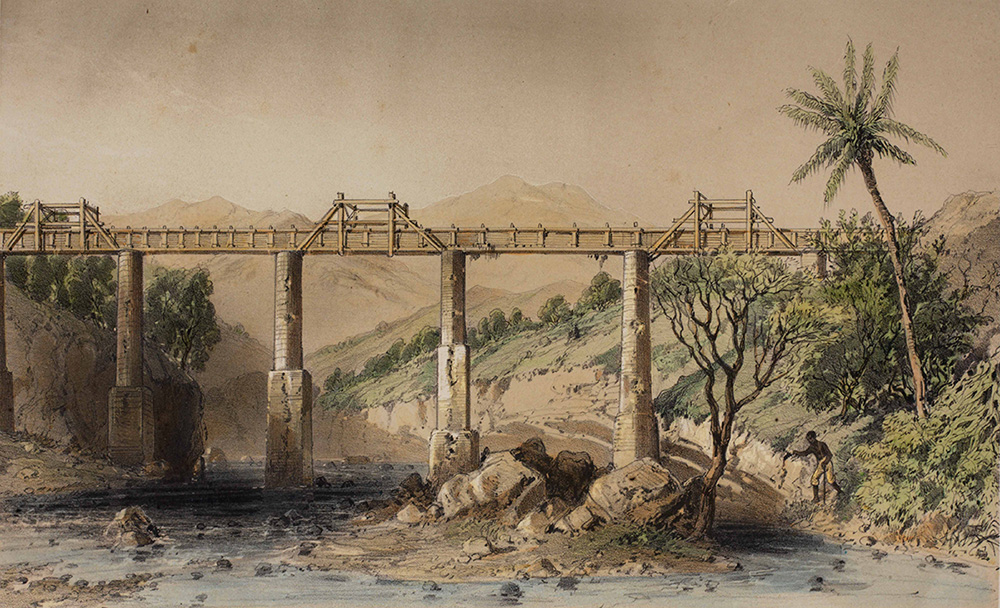

It was in this extremely favourable context that in 1816 and 1817 Jean-Valfroy Dehaulme (1748-1819) and Jean-Baptiste Couve requested concessions of water from the colonial administration, aimed at powering the mills they wished to set up in the factories that they each planned to construct on their respective estates. The first sugar refinery on the plain of Le Gol was setup by par Jean-Valfroy Dehaulme, not far from where the Pont Mathurin bridge now stands. For reasons that have not yet become clear, Deheaulme almost immediately decided to abandon the establishment he had set up, as well as the adjacent plot of land, selling it to Mr Pinard. This section, separated from the “lower” estate, was purchased by Louis Gervil Ady as from 1827, then by Joachim and Anaïs Ferrère-Gautier from 1830. Acquired by Émile Laisné in 1837, the latter was forced to transfer the estate to the Ferrère-Gautier in 1839, the taking on the name of the Gautier estate.

The remaining part of the “lower” estate, where the Château du Gol was constructed, had remained the property of Jean-Valfroy Deheaulme. After his death (1819), it was handed down to his son, Valfroy Deheaulme (1782-1854) and to his son-in-law Laurent Philippe Robin (1760-1832). They set up a sugar refinery on the estate. Chronologically, this was the third sugar refinery opened on the plain of Le Gol.

The second sugar refinery (Le Gol itself) was set up in 1817 by Auguste Blaise de Maisonneuve (1786-1818), Henry Marie Salaün de Kerbalanec (1750-1832) and Jean-Baptiste Couve de Murville. Auguste Blaise de Maisonneuve died the following year.

Jean-François Placide Fortuné Chabrier was born at Lézat sur lèze, in the department of Ariège, in 1791. Originally from a modest Catholic family, he came to Bourbon Island in 1817 as a negotiator. Very soon after arriving, he married Louise Robin (1800-1832), daughter of Laurent Philippe Robin, thus becoming one of the dignitaries on Bourbon island and he developed an interest in questions concerning sugar. In 1824, he became a sugar producer in his turn after buying the estate of Le Gol from its Mauritian owners. To reduce financial risks, in the same year he sold half of his shares to Joseph Thomas Couve (1788-1853), the brother of Jean-Baptiste Couve, former owner of Le Gol.

Following “difficulties” between these two, there was a court case aimed at dissolving the company. The result was that in 1825 the entire estate of Le Gol was purchased by Chabrier. The property remained in the family until 1905, with the exception of a short association with Théodore Deshayes, who also owned Pierrefonds. From then on, Chabrier, a clever businessman who knew when to seize opportunities, worked on reconsolidating the estate originally the object of the concession granted to Desforges Boucher.

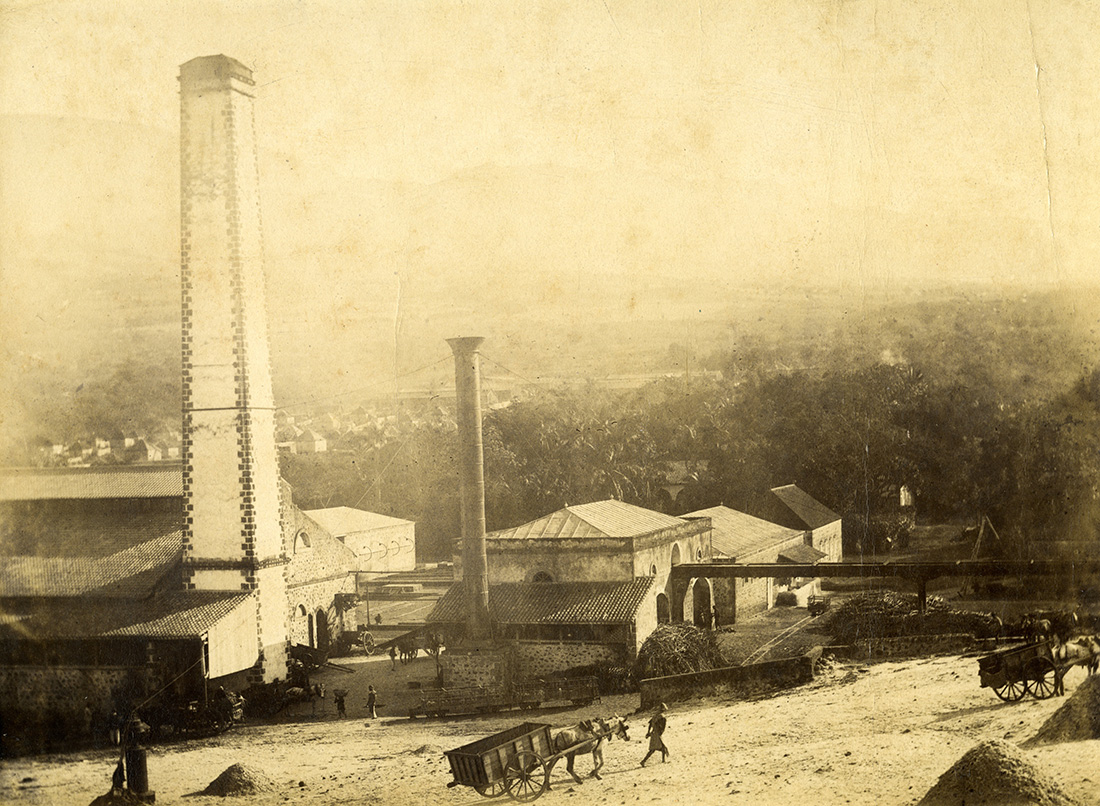

In 1831, there were 316 slaves working for the sugar producer. In 1834, he acquired the estate of Château du Gol: he now owned 522 hectares of cultivated land, of which 251.5 were planted with sugar-cane, 7.5 with coffee, 2.5 with cloves, 7.5 with cassava and the rest with various other crops, mainly food crops, or were fallow. A total of 497 slaves worked on the two estates. In 1840, Chabrier acquired the Gautier estate, corresponding to the upper section of the former “lower estate”. At this point in time, he thus reconstituted virtually the whole of the estate of Le Gol and became director of four sugar refineries (the refineries of Le Gol, Gautier, Le Château and the refinery of Bellevue, which he set up around 1834).

571 slaves, distributed between the various estates in the area, now worked here. After 1840, their numbers rose above 600, even reaching 660 in 1848. Always greater in number than the women, the men represented between 59 and 68% of the slave population, depending on the period. Through his acquisitions, Chabrier became the owner of the island’s largest single estate and one of the colony’s most powerful and most influential industrialists. The purchase of the enclaves Mondon Lory, Eugène Reilhac and François Régi came to complete his land ownership.

During the same period, the development of sugar-cane as a crop, as well as the needs of industrial production, led to an increase in water consumption. As from 1844, the estate of Le Gol consumed half of the water affected to Saint-Louis for its agricultural, industrial and domestic needs, more than those of the town itself, the sugar estate of Le Coat de Kervéguen, as well as other smaller estates. The development of sugar-cane also led Chabrier to impinge on the area around the lake. Due to the industrial activity, the refineries, like all the others, harvest after harvest discharged industrial waste that was harmful to the environment, leading the inhabitants to complain.

The small number of tourists visiting the area at the time were impressed by the size of the Chabrier refinery, an example being Théodore Pavie, who, in the early 1840s mentioned “the colossal establishment of Le Gol, certainly exceeding all the sugar refineries in the district.” The estate prospered, mainly thanks to the excellent economic conditions of the 1850s-1860s. Jean-François Fortuné Chabrier greatly increased his wealth. Like a large number of Reunionese entrepreneurs with interests reaching beyond the limits of the island and the sugar industry, he did not reside permanently in the colony. His business interests regularly led him to travel to mainland France, particularly Paris where he owned flats, enjoying the social life there, like many other eminent members of the bourgeoisie of the period. The mansion of Le Gol, inhabited very little during this period, seems to have been more or less abandoned.

At the time of his death in Paris in December 1851, he had seven children all living in mainland France: Laurence, Nanette, Ernest, Fortuné, Mathilde, Louis and Valfroy-Edouard. He owned vast sections of land and industrial structures that do not seem to have suffered from the transition from slavery to indentured labour. Until the end of the 19th century, the labour force of Le Gol was regularly increased: 598 indentured labourers in 1857, 662 in 1858, 688 in 1859, 716 in 1860 and 714 in 1900, to whom must be added 40 or so share-croppers, who, as well as working on sugar-cane, worked the land around the estate. The indentured labourers distributed between le Château, Bellevue and le Gol itself, were housed in ‘camps’ consisting of terraced dwellings and huts, growing a few crops to meet their own needs and practising small-scale animal husbandry. In the year immediately preceding the First World War, the estate still numbered 322 indentured labourers, mainly working in the fields. Most of their work involved sugar-cane, even though a small coffee factory, as well as a small cloves production plant, the remains of the estate’s initial activity, were maintained to retain speculative crops on the higher slopes of the estate.

Private collection of Jean-François Hibon de Frohen (1947- )

However, the crisis seems to have made a mark on the seven heirs of Chabrier. Living far from the land that they owned, in 1881 they sold their shares in exchange for the payment of a sum of money. In the same year, a company was set up for the estates to be managed by those who had retained their shares. Management was legally entrusted to Louis Chabrier. In 1893 the distribution of the shareholders was slightly altered: the heirs remained in the majority with 97% of the shares, but included a new shareholder: Léon Colson. The latter, who had trained as an engineer and was a former student of the École Polytechnique, had probably met members of the Chabrier family in Paris, notably Ernest, in the exclusive circles of the members of prestigious schools in the French capital. Director of the Compagnie du Chemin de Fer de La Réunion (Reunion Railroad Company) and future president of the Reunion Chamber of Agriculture, he was appointed legal manager of the sugar producing installations, which now took on the name of Colson et Cie.

For reasons unknown to us, the company was dissolved at the request of the Chabrier heirs in 1904. The entire estate was sold during the following year to Robert le Coat de Kervéguen for the sum of 900 000 Fr. The sugar producer maintained it for 15 years, during which period the refinery was developed to take in the sugar-cane of the Domaine des Cocos (closed in 1905). Le Gol thus became the most powerful establishment of the colony, with the capacity to process 850 tonnes of sugar−cane each day.

In 1920, following political and family problems, Robert Le Coat de Kervéguen sold all his belongings and estates to Mauritian buyers – the Compagnie Foncière de Maurice-Réunion Limited – for the sum of 12 million francs. Thanks to the high price of sugar at the time, this was a period of prosperity for the company.