Several years after his arrival from Bourbon island, Fantaisie had “abandoned his post” at 10, rue Pigalle. The baroness requested the police to arrest her slave, so that he could be returned to Bourbon island . This was not the first such episode in the family’s history. In 1790, the baroness’s father-in-law, Henri-Paulin Panon Desbassayns, had lost his enslaved domestic servant, François, “an entirely trustworthy mulatto” to the liberty of Paris .

While the revolutionary spirits no longer prevailed in 1823, the Commissioner responded to the baroness with “regret” that, “after careful consideration of the case,” he must inform her that his hands were tied; the police could not order Fantaisie’s arrest. “I have no other option than to exert strict surveillance over him and even to have him summoned to my Prefecture to ask him to present his Papers and to urge him to prevent, through submitting, the legal action to which his misconduct and vagrancy might expose him” . The police might harass, interrogate, and even jail him, but Fantaisie had effectively achieved his personal freedom from the Desbassayns family.

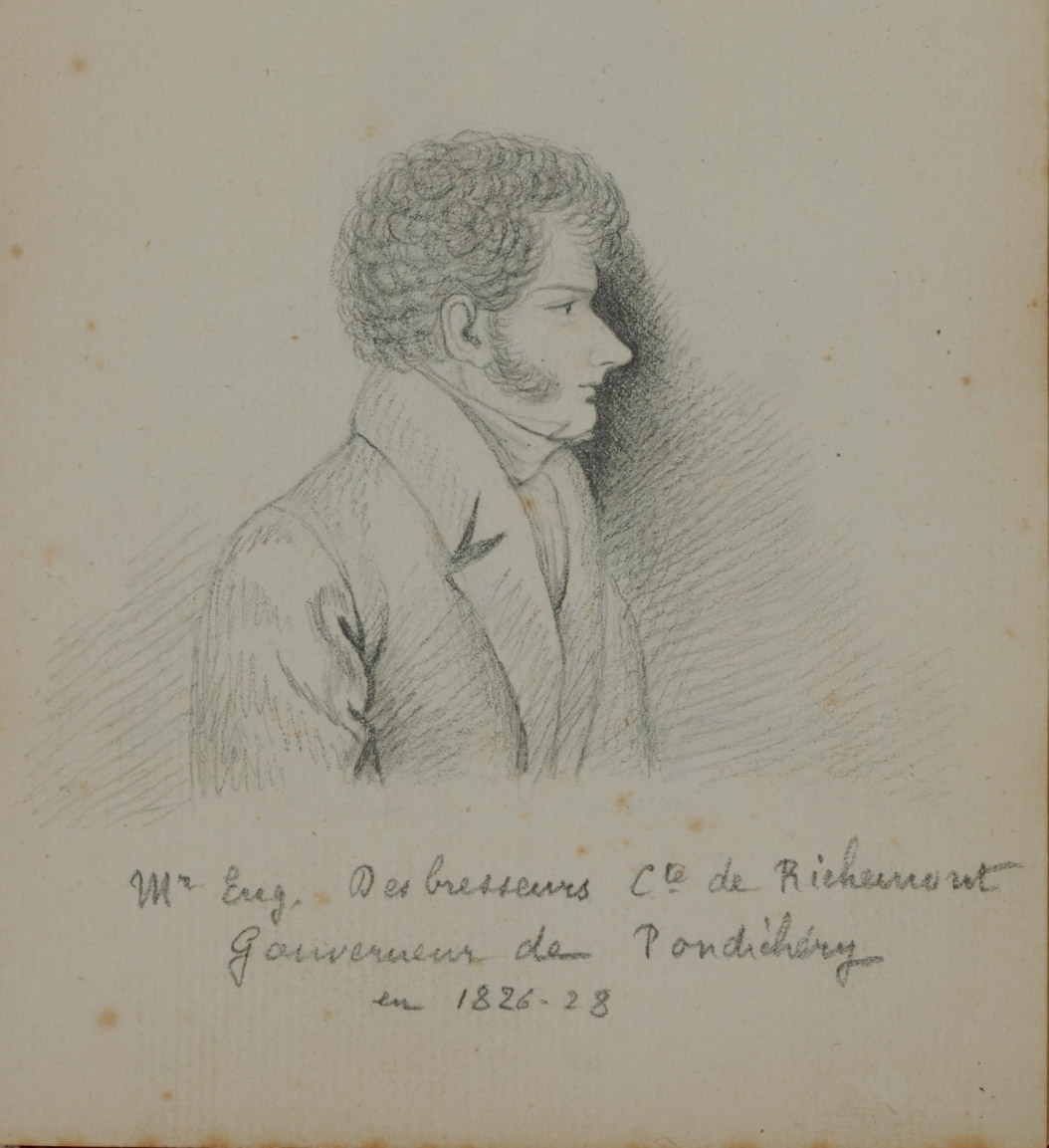

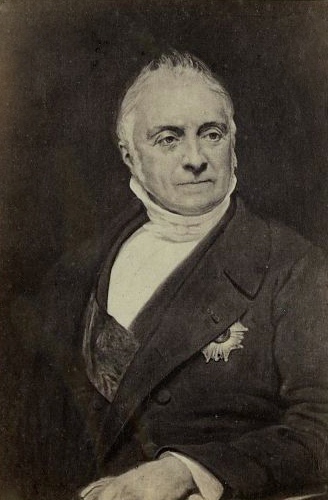

Fantaisie’s journey toward self-liberation in Paris is all the more fascinating because it took place only a few years after Furcy’s failed lawsuit for freedom in Bourbon island. In 1817, Furcy, the son of an enslaved mother and a French father, attempted to free himself from Joseph Lory, a colonist from Mauritius who had married a daughter of the island’s powerful Creole family. Lory easily obtained the support of Philippe Panon Desbassayns de Richemont, a distant relative by marriage to the same Panon clan . In the dispute with Furcy, Desbassayns proved his fidelity to the local slave-holding elite by orchestrating the opposition to Furcy’s allies – his free sister, Constance, the bailiff, Toussaint Huard, and two Paris-trained magistrates, the Procureur du roi (King’s prosecutor) Louis Gilbert Boucher, and the substitute Procureur du roi, Jacques Sully Brunet. Desbassayns effectively quashed these opponents, leaving Furcy illegally detained in the island’s prison for almost a year, to the point of near death. At the time of Fantaisie’s bold escape in Paris, Furcy remained the slave of the Lory clan, doing manual labor on their sugar plantation in Mauritius .

“Fantaisie” was born around 1804, presumably somewhere between modern Mozambique and Kenya, where he would have received a name in his parents’ language . We don’t know how or when he was transported to Bourbon island, but somehow he became the slave of Ombline Gonneau-Montbrun, widow of Henri-Paulin Panon Desbassayns of Saint-Paul . Like the many branches of the extended Panon clan, Ombline lay claim to a plantation on one of the island’s choice parcels of land, and purchased hundreds of slaves to grow maize, rice, coffee, and, eventually, sugar .

The name “Fantaisie” appears in both the baroness’s 1823 letter to the Paris Préfet de Police and an 1821 colonial report to the ministry, where Fantaisie is described as belonging to the ‘Widow Panon Desbassayns’ and arriving at Rochefort with her grandson, Eugène Desbassayns .

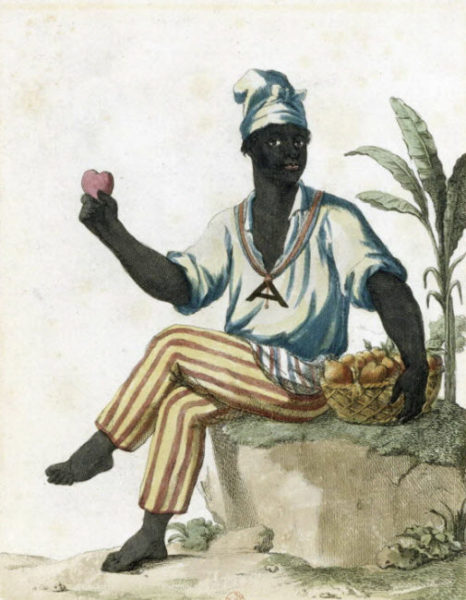

Anonymous. Between 1828 and 1842. Drawing, graphite.

Collection of Villèle museum

Several possible explanations arise. Perhaps one of the widow’s cafre (African) slaves was rechristened “Fantaisie” just as he departed for France with Eugène in 1821. Colonial slave owners could assign names to their slaves at whim. Ombline listed two fourteen-year old cafres – Fleurisson and Philogène – as domestiques (domestic servants) in her 1814 census return, which would make either of them about the right age at Eugène’s departure for France. However, both names reappear as cultivateurs (agricultural workers) (ages twenty-two and twenty-three) on the censuses of 1822 and 1823, so it is unlikely that either of these youths was the secret identity of “Fantaisie” . A more likely explanation is that Ombline, like many other wealthy planters, neglected to declare Fantaisie on her censuses because she held him illegally, smuggled into the colony from Africa following the 1811 slave trade ban . At some point, Ombline must have selected him to be trained for service, and it was in this capacity that he became the companion to Ombline’s grandson, Eugène Desbassayns, aboard the king’s corvette La Sapho, arriving in Rochefort on 13 April 1821 . A third possibility combines the first two explanations: smuggled into Bourbon in violation of the ban, named Fleurisson or Philogène and trained as a servant, “Fantaisie” assumed his new name on the eve of his departure and the old name was transferred to a newly smuggled African slave on the widow’s plantation . Finally, Ombline may have purchased the enslaved servant Fantaisie from another colonial family close to Eugène’s departure, such that he never appeared on her extant censuses.

In the wake of Furcy’s affair, Philippe Desbassayns de Richemont assumed the post of Commissaire Inspecteur pour le Roi des Etablissements français dans l’Inde (King’s Commissioner and Inspector for the French Establishments in India) . Accompanied by his wife, Eglé Mourgue, their son, Eugène, and three enslaved domestic servants, Christophe, Ozone & Agathe, Desbassayns departed Bourbon for Pondicherry on 21 July 1819 . It is not clear when Eugène left India, but he must have passed through Bourbon late in 1820, when he likely acquired Fantaisie from his grandmother, Ombline. Eugène then traveled independently from his parents to France, arriving with Fantaisie in Rochefort. According to law, at this point Eugène should have arranged for Fantaisie to be housed in the port depot, awaiting immediate return to Bourbon island, in order to prevent his entry and effective liberation in metropolitan France.

French Free Soil policy, which liberated any slave who set foot on French soil, was complicated, having vacillated over the course of centuries. It originally emerged in the fourteenth through seventeenth centuries, primarily in contest with the expanding Spanish empire, and flourishing during the reign of Louis XIV. The royal edict of October 1716 and the Declaration of 15 December 1738 effectively suspended the Free Soil principle when French masters brought their slaves to the continental kingdom, under certain conditions . However, the Admiralty Court of Paris refused to enforce these laws because the Parlement (High Court) of Paris did not recognize slavery in metropolitan France; this effectively liberated hundreds of slaves who had accompanied their masters there . In 1777, Minister of the Navy Antoine de Sartine, the former Commissioner of the Police of Paris, hit upon a solution: the Déclaration pour la police des Noirs (Declaration for the Policing of Blacks) would ban the entry of “all Blacks, mulattos or other persons of colour of either sex” . By using the language of race instead of slave status, the law effectively circumvented judicial opposition. Moreover, the Police des Noirs established depots in France’s main ports, where non-whites were to be confined awaiting the next available ship returning to the colony of origin. This system, however, met with continued resistance by courts, port officials, and – not least – the slaves themselves. During the Revolution, the Constituent Assembly’s decree of 28 September 1791 resurrected the Free Soil principle, declaring, “Any person who enters France is immediately free”, but Napoleon restored the police des Noirs racial quarantine in 1802 . Finally, in 1817, Mathieu Louis, Count Molé, the Minister of the Navy, began to modify this policy. He suppressed Article 3 of the 1777 law, which had ordered the arrest and deportation of “Blacks or mulattos who had been brought [or introduced] into France”, with the net effect of placing the burden of returning slaves to the colonies on the masters . Masters who neglected to place the slaves in port depots upon arrival risked the loss of their slaves, and the Ministry refused to intervene on their behalf.

Eugène was one of the scofflaws who chose not to place his slave in a port depot for immediate return. From Rochefort, the pair continued to Le Havre, where Eugène asked permission to bring Fantaisie with him to Paris. Refusing, the port official reported on the incident to the minister of the Navy:

“Mr. Desbassayns, a pupil of the naval administration, received from the Governor of Bourbon authorization to be accompanied to France by a black accustomed to providing him with the care required for his health: on the basis of the same motive, Mr. Desbassayns requests that this servant may follow him to Paris. Although the position of an administrator during the trip cannot, in the context of the report in question, be assimilated to that of a colonist, the provisions of the dispatch of October 17, 1817, are too precise for me to consider myself exempted from informing your Excellency of the request granted” .

Together, Eugène and Fantaisie made their way to Paris and set up residence at the family mansion at 10 rue Pigalle, awaiting the arrival of his parents from India .

Eugène’s ongoing ill health is confirmed in a chatty letter to his grandmother Ombline, while he awaited his father’s imminent arrival in Nantes. Much of the letter is difficult to decipher, due to its fragile condition, but Eugène clearly mentions “a pain I have in my side” and “the Doctor bled me” . However, there is no mention of his grandmother’s slave, Fantaisie, which probably indicates that he continued to serve Eugène without incident in Paris for a time.

The Baroness Desbassayns de Richemont reported Fantaisie’s escape over a year later, in the autumn of 1823. No extant records explain why he left the family’s service, but one can imagine that the arrival of the parents changed the dynamics in Eugène and Fantaisie’s dyad.

Fantaisie probably obtained key information and inspiration for his escape from a network of free people of color in Paris, for Madame Desbassayns’ complaint was only the latest in a stream of letters to the ministry from frustrated masters seeking to recover their absconding slaves. Late in 1821, for example, a master from Martinique complained that the slave who had accompanied him to Paris “claims to remove himself from my rights as owner” . The Council of Ministers, ruling on his request in March 1822, had determined that “the laws applicable in mainland France in respect of persons do not permit any legal action of the type he requests to enable him to cease the disobedience of his slave” . In June 1822, another slave from Bourbon, Tranquillin, declared himself free from his master Jean-François Dancla in Bagnères-de-Bigorre, enlisting a lawyer to write a brief claiming Tranquillin free “through the effect of his prolonged stay on the Continental territory of the Kingdom” . From these and a series of similar affairs, Fantaisie probably learned that the authorities would not intervene on behalf of the Desbassayns.

After the baroness complained to the Commissioner of Paris, the police traced him to 65 rue St. Nicolas, across the city, at the home of one François, “coloured man” and musician . However, the police could not issue orders to arrest Fantaisie without cause. He fell under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of the Navy, and without the minister’s order, the police could not deliver him to a port for deportation. “He would have had to be guilty of an offence or been in a state of vagrancy, in which case he would immediately have been placed at the disposal of the judicial authority, to be judged in accordance with the law, which, as regards application of sentences, admits no distinction of origin” .

Fantaisie’s escape was not only an individual affair. His actions prompted the ministry to reconsider its policy regarding colonial slaves brought to the kingdom who escaped their master’s control. In November 1823, reviewing the clauses of the original 1777 police des Noirs, especially Article 3, which provided for the arrest and return of Blacks brought to France, and Article 12, which ensured that their “status” (i.e. slavery or freedom) remained unchanged while they were in France, an anonymous colonial functionary drafted a letter to the Commissioner of Police on behalf of the Minister of the Navy. Drawing upon the preamble to the 1777 police des Noirs, which justified the exclusion of all non-whites from metropolitan soil in order to prevent “the highest disorder … particularly in the capital” , this bureaucrat noted that:

“The result of the spirit of the legislation is that it is absolutely in the interest of the Colonies for black slaves who have been brought to France by their masters to be immediately sent to their workshops; in addition, it is equally in the the interest of order that France should send away isolated Individuals who would only increase the number of vagrants and indeed, whose presence has a tendency to alter, with no Compensation, the purity of European blood” .

The minister, Gaspard de Clermont-Tonnerre, reviewing this draft, crossed out the last phrase about mixing of blood. Nevertheless, he validated the Commissioner’s proposal that the police should have the authority to arrest fugitive slaves and deliver them to the port authorities, where they would return to the jurisdiction of the Ministry of the Navy: “According to this opinion, which I share, I have no doubt, Monsieur [Police Commissioner], that you can bring back to the depot the black man in question [Fantaisie].” However, there is no indication that the undated letter was ever sent. A note in pencil states, “information to be retained” .

Enthused with the Commissioner’s proposal to use the kingdom’s interior policing powers to restore fugitive slaves to the naval authorities, Clermont-Tonnerre brought this idea to the Council of Ministers for discussion in November 1823. However, the Council rejected the proposed solution and instead decided “that the transport of slaves from the French Colonies was to be banned entirely” .Therefore, in March 1824, the minister sent a circular letter to all colonial governors suspending the Police des Noirs, and forbidding colonial administrators from authorizing travel for any slaves who would leave the colonies, for France or any other destination. Royal policy thus reinforced the sharp division between colonial slavery and metropolitan freedom (status), while distancing itself (as it had throughout the Restoration) from exclusion on the basis of race .

The ban on slave mobility, justified by the need to retain colonial labor following the slave trade ban, remained France’s policy until 1830, when the July Monarchy reverted to allowing slaves who escaped their masters in metropolitan France to become de facto free. In 1835, Furcy embarked upon his appeal of his enslavement to the Cour de Cassation (France’s highest court of appeal) on the basis of his mother’s brief residence on the Free Soil of France in 1771 . The following year, Louis Philippe formalized the Free Soil ordinance, officially recognizing all people who arrived in metropolitan France as

free .

In their council of November 1823, the Ministers rejected the Commissioner’s proposal that the police arrest and deliver him to the port depot in Brest, for return on a royal ship to Ile Bourbon. “For this individual, the Council considers that there is nothing to be done” . Thus, Fantaisie apparently achieved his freedom and continued to live undisturbed in Paris.

It is an irony of history that, once beyond the surveillance of the police and the rest of the French state, Fantaisie disappears from the archives. Today, he also enjoys his freedom from our historical scrutiny. We can only imagine him listening to the music of François and searching for a position as chef or valet, waiting for spring to return to the cold, gray city of Paris.