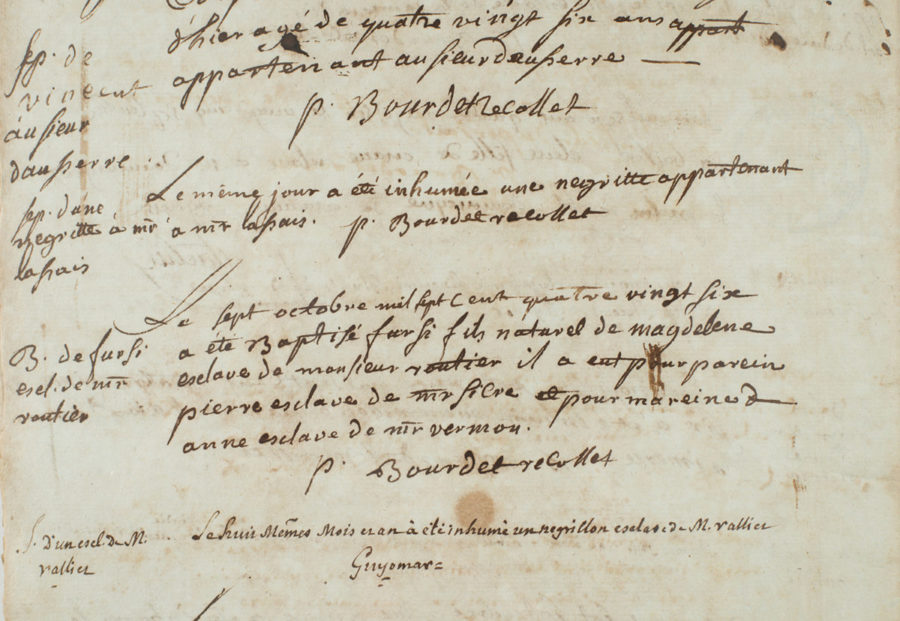

However, throughout his life, Madeleine’s son Furcy would never experience the same freedom.

Unlike his sister Constance, who was freed shortly after her birth, Furcy was not allowed to come and go as he pleased, to express himself freely, to get married, to bear or raise children: in short, everything that gives meaning to the life of any individual.

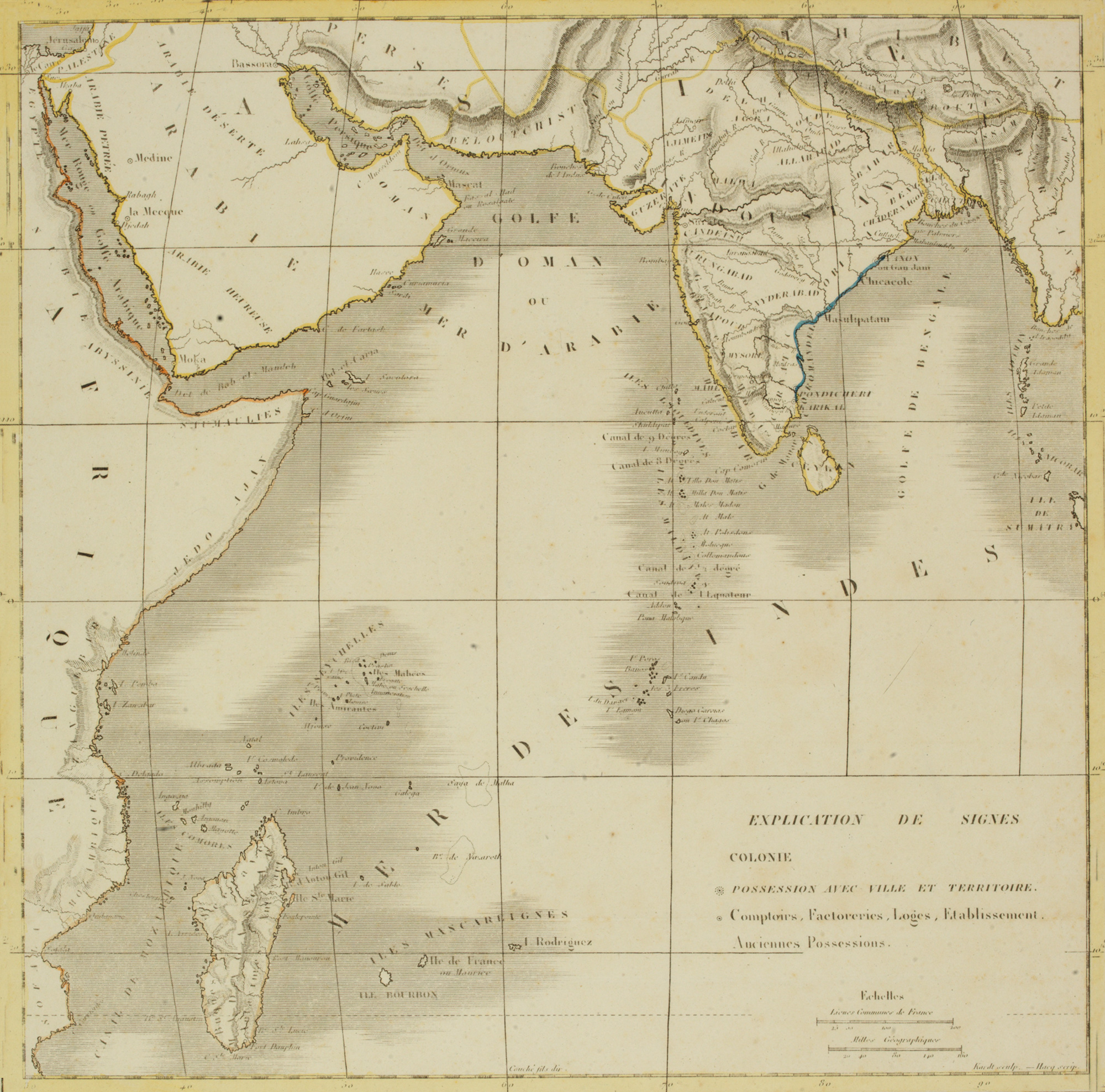

This was made even more unlikely as he lived on an island where slavery had become a driver for economic prosperity and social and political organisation. An island which was far removed from any development of ideas or revolutions, as seen in Haiti or Mainland France. An island which was closely linked to Isle de France, where a French delegation that had arrived in June 1796 to announce the abolition of slavery was promptly sent straight back, without ever even stopping in Reunion Island.

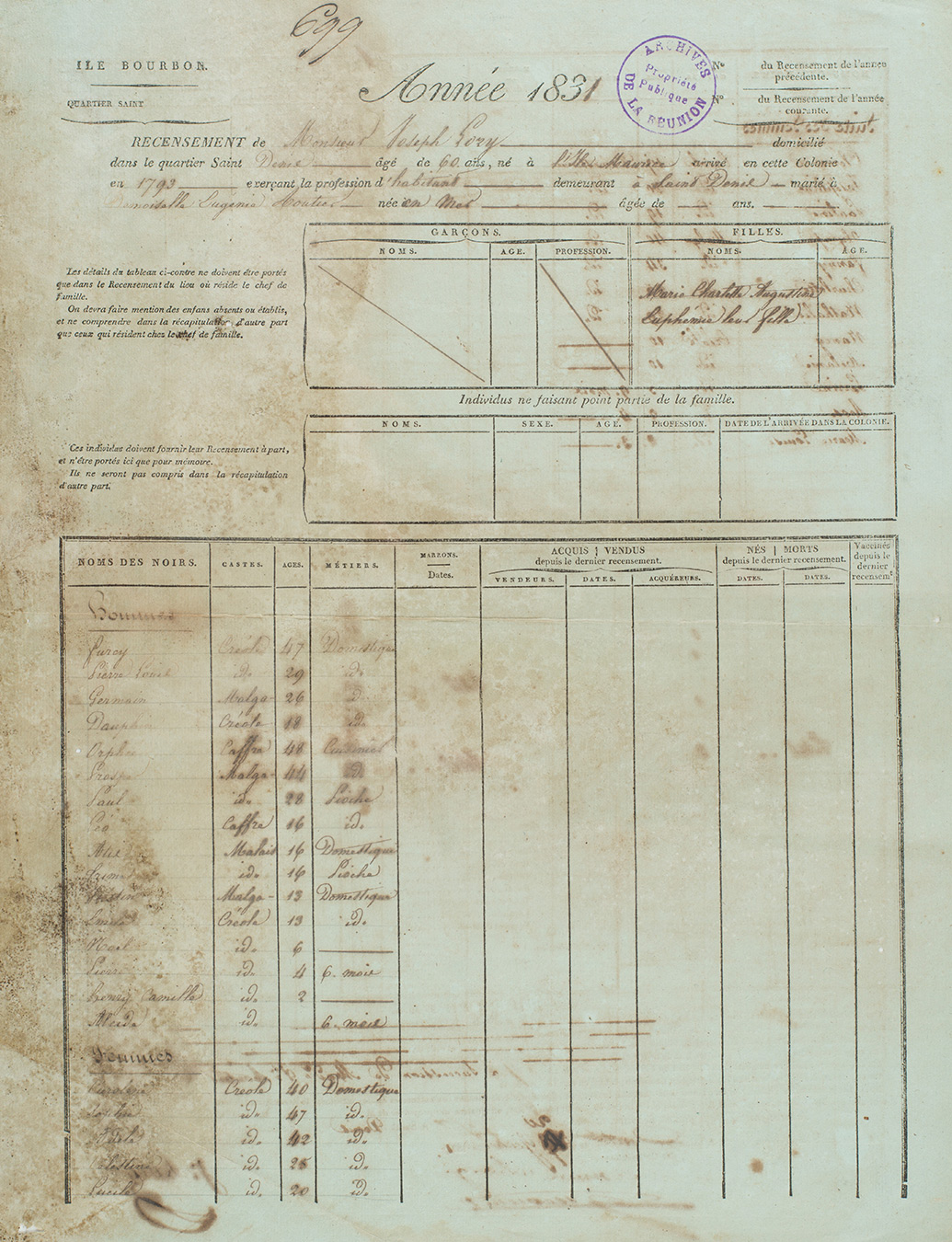

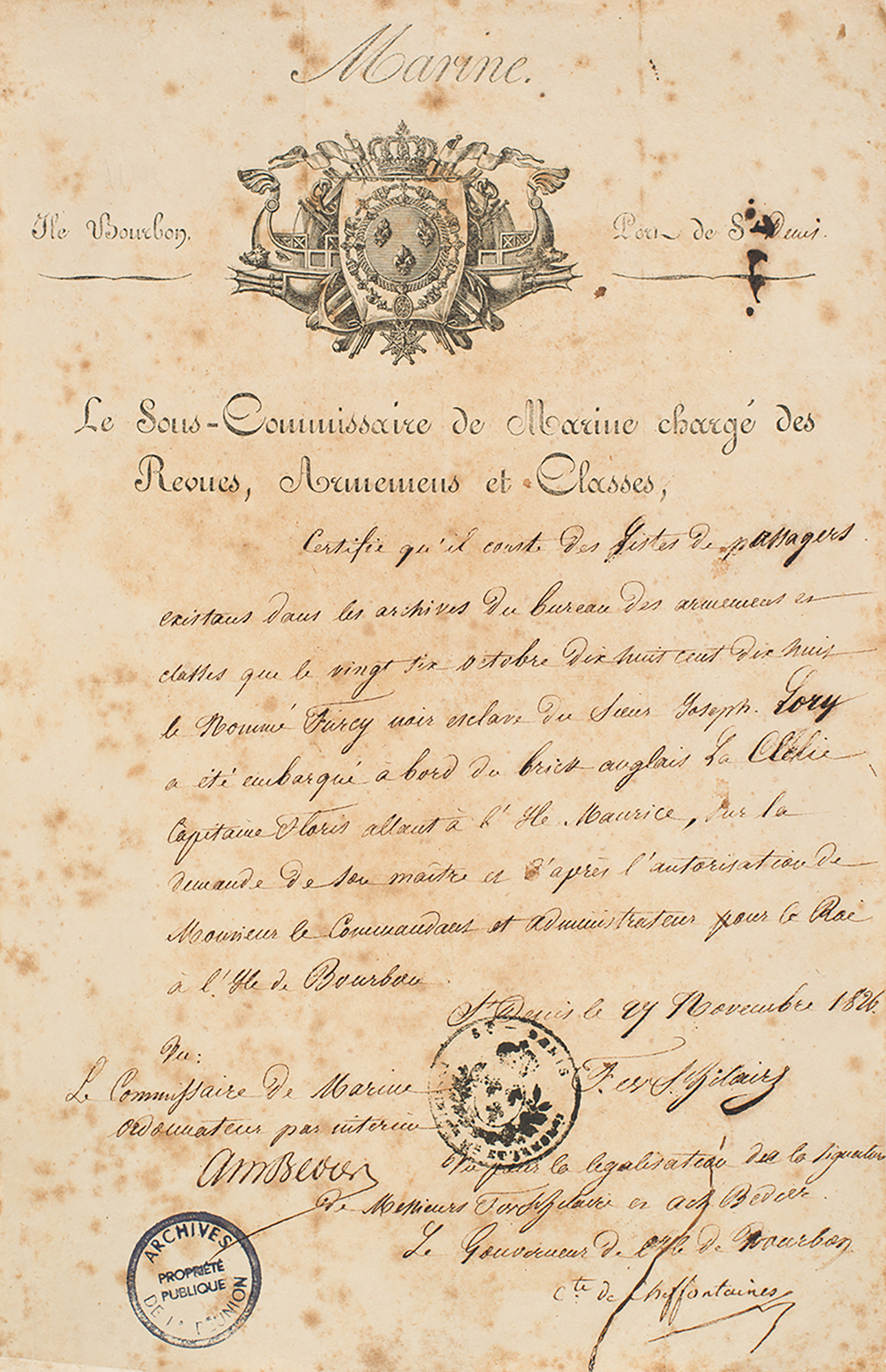

Moreover, Furcy belonged to a slave-owner who was as powerful as he was greedy, refusing any kind of ‘arrangement’. Such efforts had ended in failure, ending up with Furcy being both manipulated and intimidated by his master, Joseph Lory.

In this doubly hostile context, the only possible way out for Furcy was to seek justice by turning to a man whose arrival had raised the hopes of many others.

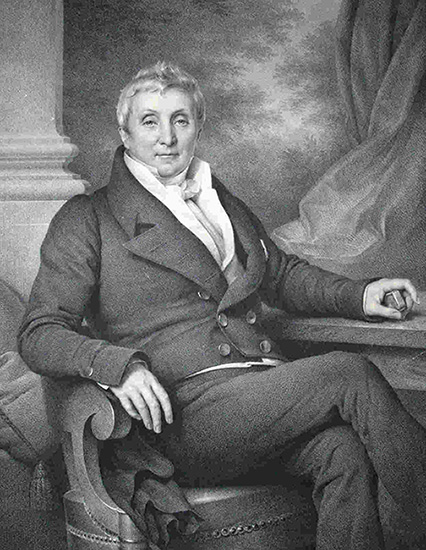

In December 1816, seeking greater control over the appointment of judicial personnel, the Crown appointed Gilbert Boucher as Attorney General at the Royal Court of Bourbon, a magistrate who was already aware of the need to improve the judicial system out in the colonies.

As the island’s highest ranking judicial officer, Gilbert Boucher took his mission seriously upon arrival in June 1817, and just a few weeks later he had dismissed three judges from the lower court for corruption, drunkenness and favouritism.

On such a small island, it is likely that these important decisions did not go unnoticed, on one hand raising hopes among the most deprived, while on the other hand stirring concern and even disapproval among those whose interests were threatened by such requests for freedom.

And so, in November 1817, Furcy’s sister Constance presented a proclamation to the public prosecutor’s office of the royal court of Bourbon in order to explain her brother’s situation.

This approach would change Furcy’s life, for better and for worse.

***

Faced with Constance and Furcy’s request, Gilbert Boucher and Jacques Sully-Brunet suggested that they did not take Joseph Lory to court directly, but rather to officially notify him that Furcy considered himself as free man, and not a slave.

When, on 22nd November 1817, Joseph Lory received a visit from a bailiff announcing Furcy’s self-proclaimed freedom, the wealthy slave-owner’s blood started to boil. Within an hour he marched off to the royal court to complain to the Public Prosecutor, who tried to calm him down, advising him to carry out legal proceedings in order to obtain “the provisional restitution of his slave” .

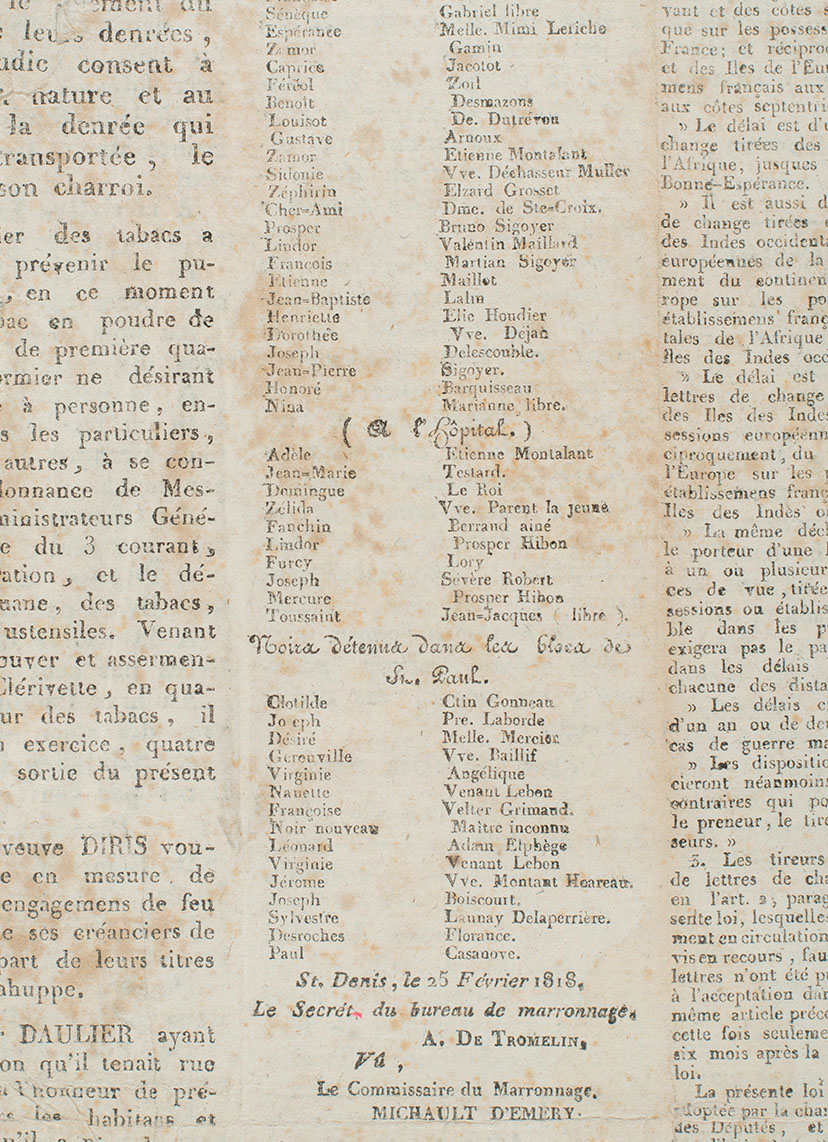

Ignoring both advice and procedure, and above all to avoid losing face, Joseph Lory first decided to discipline the bailiff who had dared to serve him with the deeds, then declared that Furcy was in fact an escaped slave, having him arrested and incarcerated.

Dismayed by such behaviour, Gilbert Boucher immediately alerted the various authorities to the illegal nature of this arrest, as well as to the likelihood that Furcy was not Monsieur Lory’s slave.

In addition, he swiftly brought together the magistrates of the public prosecutor’s office under his jurisdiction, seeking their opinion in particular on the following issues:

– “Could Indians have been enslaved in the Colony in 1779 or indeed before or after?” The common opinion that emerged was that it would be politically dangerous to doubt the status of thousands of Indians as slaves.

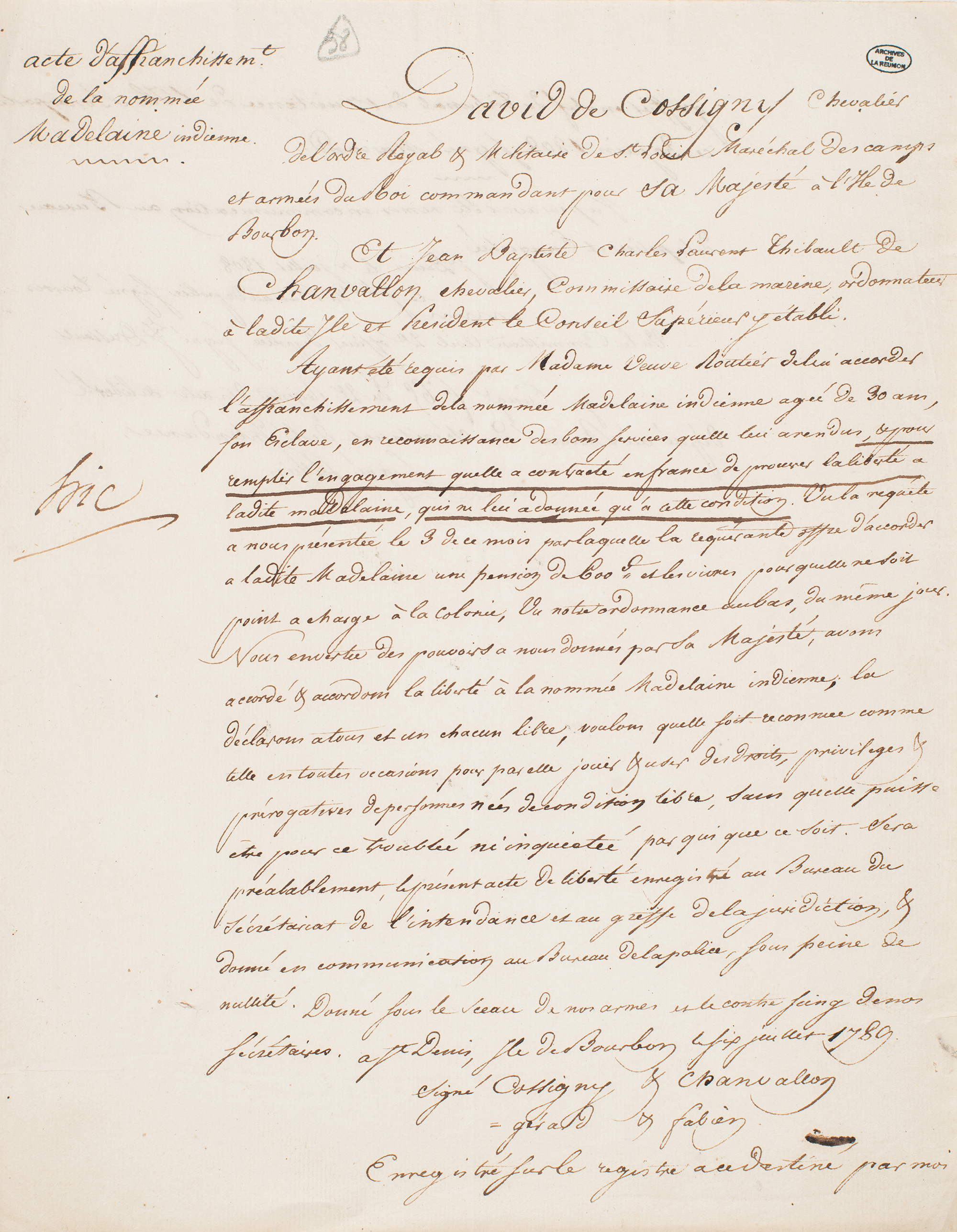

– “Would an Indian who had been brought to France as a slave regain his freedom by the mere circumstance that he had set foot on French soil?” The Public Prosecutor and his auditing adviser were the only ones to answer this question in the affirmative.

– “Could an Indian sold as a slave in India and brought to France be the object of a contract in France, either paid or non-paid?” No, according to Gilbert Boucher, because “a slave from the colonies brought to France was never considered a commodity in the kingdom”. In any case, “Madeleine had been handed over as a deposit and was not sold”.

The minutes of this meeting, kept in the Departmental Archives of Reunion Island, show the conflicting positions between the Public Prosecutor on the one hand and his Advocate General and the King’s Prosecutor on the other, the latter having been in office for a long time, linked to local interests and under the influence of Monsieur Desbassayns, a rich landowner.

Faced with this unbearable situation in which he found himself both isolated and threatened, the Public Prosecutor contacted his superior, the Minister of the Navy and Colonies, to denounce these illegal acts committed against Furcy and the related pressure exerted on the judiciary. This would be in vain, as his letters would not arrive until he himself had returned to Mainland France (see below).

As for Furcy, he appealed against both his arrest and imprisonment, his lawyer Maître Petitpas pointing out that:

– as his mother had been Indian, she could never have been a slave,

– according to the rule ‘no one is a slave in France’, she had been free the moment she arrived on French soil,

concluding that:

– Madame Routier had no proprietary deeds,

– Madeleine had been freed,

– as she had been born an Indian and thus a free woman, Furcy could not be a slave.

The lower court in Saint-Denis turned down his appeal on 17th December 1817 thus considering Furcy was indeed a slave, on the grounds that :

– it was unjustified that his mother “was a free person at the time she was transferred by Demoiselle Dispense to Lord and Lady Routier, who registered her as a slave for sixteen consecutive years”,

– given that Furcy had been born while his mother was a slave, children who were less than seven years old when their mothers were freed did not benefit from the same outcome.

Furcy’s fate was thus sealed, as was that of his defenders: having lost the confidence of the island’s authorities, he was shunned and, as the father of a new-born baby, Gilbert Boucher resignedly left Reunion in December 1817, barely six months after his arrival. As for Jacques Sully-Brunet, he was suspended from his duties.

***

While the Lower Court of Saint-Denis turned down Furcy’s appeal, it also ordered that he should no longer be imprisoned, and be “handed over to his master within three days of the judgment being served on him”. Despite this, Furcy was detained illegally and then, having become a local nuisance, sent to Mauritius in 1818, which had been English since 1810, where he was put to hard labour on the Lory family’s property for ten long years.

Having never given up his cause, Furcy had the English authorities establish in 1827 that he had never been declared as a slave by either the police or the customs authorities, nor listed in any censuses in Mauritius: from there on, he was considered to be free. As a free man, he could finally live his life, and went on to become a prosperous trader.

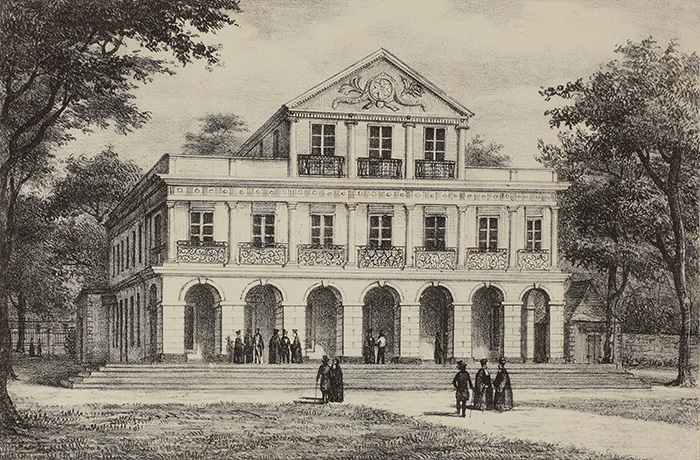

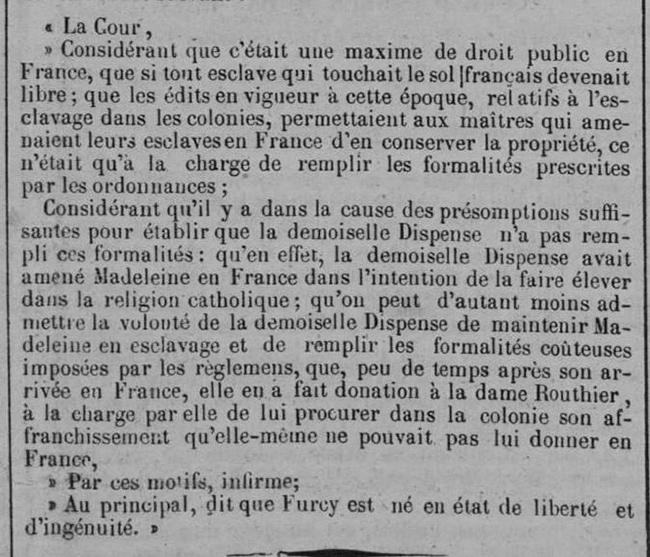

This first victory on foreign soil was followed by a second in France: on 29th April 1835, the Court of Cassation overturned the decision of the Court of Appeals of Saint-Denis, referring the case to the Royal Court of Paris, which finally settled the question of Furcy’s status on 23rd December 1843: it declared Furcy free since his birth (he was 56 years old at the time) on the following grounds:

– every slave who lands on French soil becomes free,

– while the edicts in force relating to slavery in the colonies at that time allowed the masters who brought their slaves to France to retain ownership of them, they still had to fulfil the necessary legal formalities;

– in this case, Miss Dispense had not fulfilled said formalities, bringing Madeleine to France, not to keep her as a slave, but to raise her in the Catholic faith, thus donating her to Madame Routier in order to ensure her emancipation.

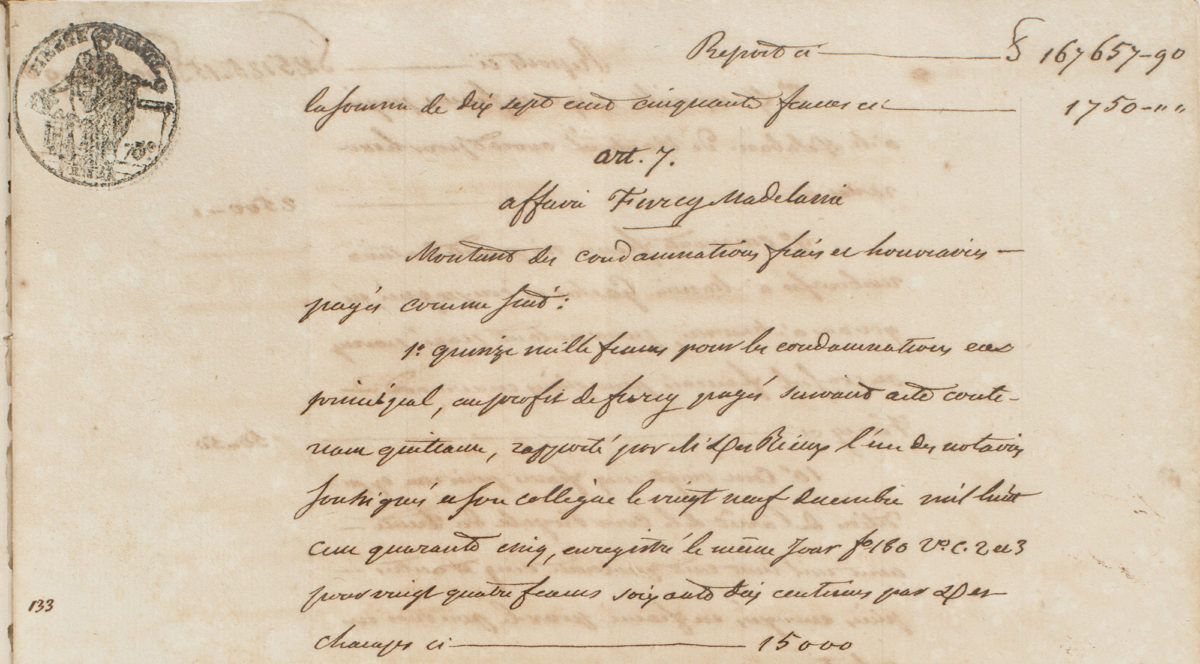

The final stage in Furcy’s legal battle took place on 30th August 1845, when the Royal Court of Bourbon awarded him damages of approximately 311,000 euros , three times more than the sum awarded in the lower court by judges with a strong local influence who, although they had had to respect the supreme court’s decision, nonetheless tried to minimise the liability of Joseph Lory, suggesting that he had acted in good faith…

***

Thus ended Furcy’s legal battle, twenty-eight years after his master was notified of his status as a free man, and three years before the abolition of slavery.

A victory with such a bitter taste, given that it had taken so long and had required such sacrifices, in a struggle against a master capable of imposing arbitrary imprisonment and forced labour.

This legal story says much about how the law and justice of Bourbon became subjugated to local economic and political interests. Furcy’s salvation, first considered by a courageous but lonely magistrate, Gilbert Boucher , was at first only possible thanks to Anglo-Saxon law in Mauritius, and then following court decisions of the highest jurisdictions in France, 10,000 km from Reunion .