Today, there exists no centre entirely dedicated to interpreting, transmitting and disseminating the history of maroonage and the existence of the Interior Kingdom, which lasted for almost 185 years and had a social organisation based on the chiefdoms in Madagascar.

In Reunion the year 1998 marked the celebration of the 150th anniversary of the abolition of slavery. Through an important topical exhibition entitled Regards croisés sur l’esclavage : La Réunion 1794-1848 (Comparative visions of slavery: Reunion 1794-1848), held at the Léon Dierx art gallery in Saint Denis, the commemoration was the occasion to take stock of existing facts and sources of knowledge on the history of slavery and the slave-trade in Reunion.

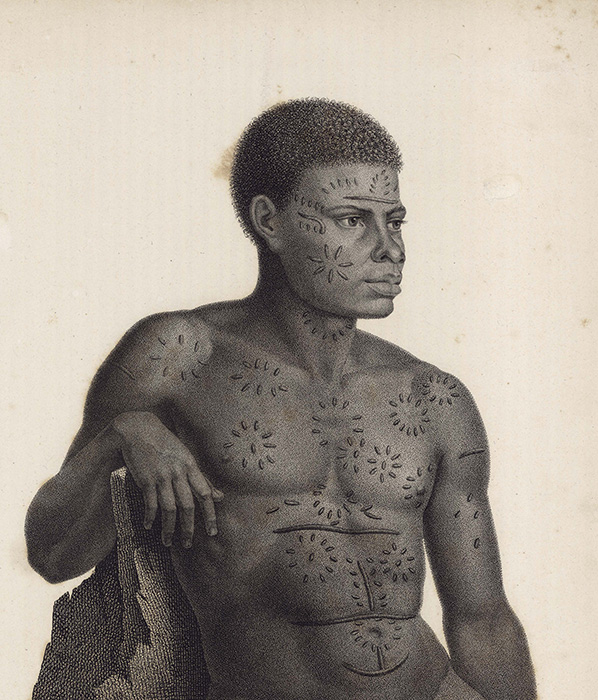

The event brought to light a number of historical sources. Alongside a range of texts, it focused on the existence of an iconography and map documents that to this day have not been fully exploited, notably those dating before 1794. In addition, the celebrations made it possible to carry out an analysis of the issue of places of memory around slavery. Very often, such analysis has been carried out through associative bodies. In March 2007, the cyclone Gamède, sweeping along the beach in Saint-Paul and destroying part of the wall surrounding the coastal cemetery unearthed the presence of human remains buried in the sand on the beach. The State authorities immediately brought in an archaeologist to carry out research. The archaeological analysis of the bones found revealed that they belonged to slaves, some of whom had been new arrivals, as was witnessed by an analysis of their teeth, which had been objects of ritual processes such as filing of incisors and canines into a point. Only the first enslaved persons arriving, originating in African populations living along the coast and further inland, bear such traces of ritual bodily alterations, which then disappeared in the context of the segregated slave-owning society of Bourbon with the first generation of slaves born on the island.

Collection of Reunion Departmental archives.

The two events, ten years apart, allowed us to put into perspective the topic of maroonage in the context of the history of slavery in the colony. Distinct approaches, separating ‘research’ and ‘the field’, have often been adopted in the recent past, when researchers and the civil society limit their processes to their respective fields of activity and do not communicate, or at least only do so to a limited degree. Today, we consider it necessary to combine the two approaches and also to refer to other fields of human science such as ethno-linguistics, onomastics, anthropology, archaeology, comparative literature, genealogy, as well as ancient and contemporary mapping, making it possible to add a more global dimension to the interpretation of our knowledge of the territory and its history.

The multi-disciplinary research carried out from 2013 to 2016 by the Service Régional de l’Inventaire (SRI) of the Regional Council of Reunion today provides answers to questions that remain unresolved, such as those of the day-to-day living conditions of maroons, their itinerary and settlement in the island’s interior, as well as their social organisation…

Any study of maroonage necessitates familiarity with the range of knowledge and findings around the issue. Such documentary and bibliographic research also involves a study of all the works of scientific research disseminated through academic networks, public structures such as archives, libraries, specialised documentation centres and private collections. We have also drawn up a list of works on the subject of maroonage through an exploration of fields of historical research, as well as artistic productions and novels. This approach makes it possible to analyse the current state of study around the topic, putting into perspective important notions such as common myths, when we take on a study of maroonage. We can thus note the porous character, or its absence, between research and literary production, as well as its presence in literary and artistic creation.

In Reunion, the places currently housing and conserving documents list approximately 600 titles, scientific articles, conference proceedings, theses, dissertations, as well as sound and video recordings. Only 15% of these directly focus on the topic of maroonage. Does this mean that maroonage is simply an epiphenomenon of slavery or that researchers have not found sufficient historical material to draw up their analysis? Does the topic involve a number of taboos that are best left alone?

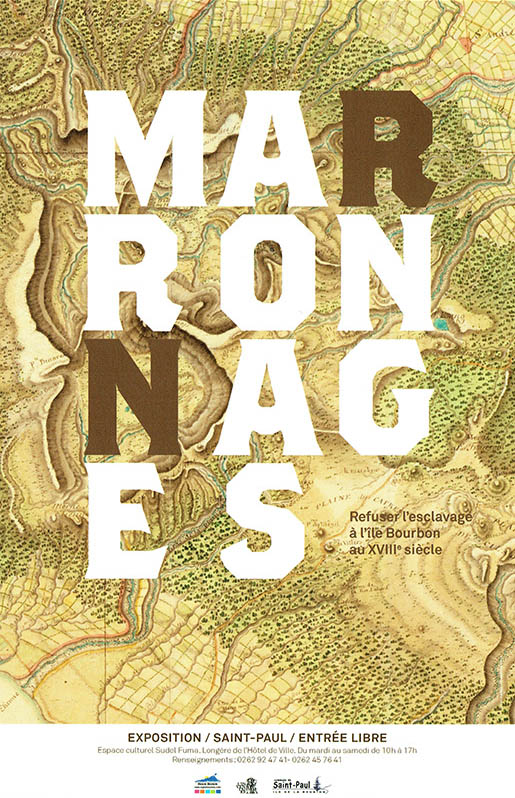

Producing research and updating it regularly is an act of citizenship which enables the society to better define itself collectively in relation to its history and territory. However, such knowledge is not particularly useful if it remains confidential, which is why since 2016, the SRI has been presenting the exhibition ‘Maronages : Refuser l’esclavage à l’île Bourbon au XVIIIe siècle’ (Maroonage: Refusing slavery on Bourbon island in the 18th century) . The exhibition consists of a cultural outreach itinerary organised around five sequences.

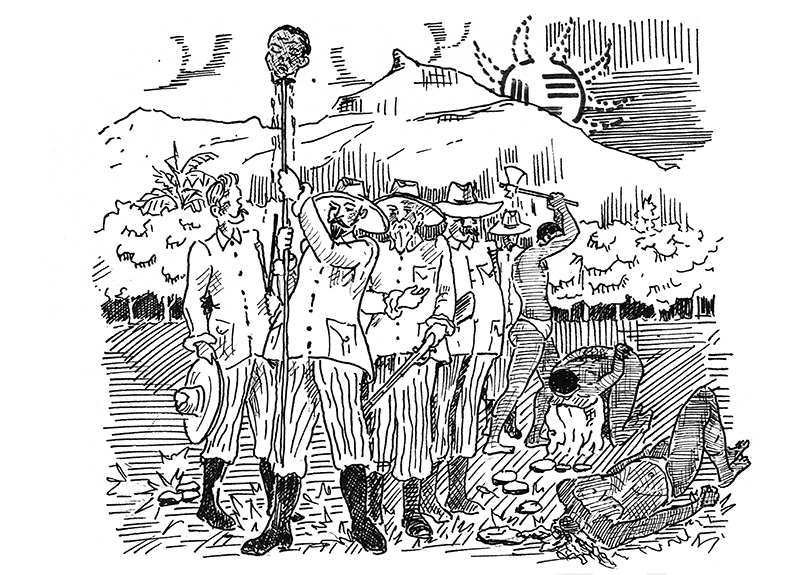

In 2013, we started carrying out research on maroonage based on reports submitted by ‘detachments’, documents stored in ‘section C’ of the Departmental Archives of Reunion (ADR). These reports were fairly irregular in terms of density of information and it appeared necessary to have both a critical vision of the documents in order to examine their level of reliability and at the same time create the necessary context for understanding them. Consequently, we decided to study the person of François Mussard, in order to situate him in his cultural, economic and political context. He is the person around whom the documents provide the most information. The aim was to study his social environment in order to integrate into the analysis other documents from section C that refer to him (localisation of requests made by estate-owners, enabling us to understand his methods of apprehending the territory, payments in the form of ‘pièce d’Inde’ – healthy male slaves – placed in the estates). Loran Hoarau, who developed the original approach, drew up the genealogy of each of the members of the detachments, tracing back to the original arrivals, notably through the Dictionnaire Généalogique de Bourbon. This process enabled him is to identify the religious and civic links between members of the same detachment, but which are not mentioned in the reports of each detachment. In addition, the civil status documents add details concerning the professions and careers of the members of each detachment. Loran Hoarau’s technique gives us a more precise vision of each detachment and the mechanisms that explain how it was composed, its hierarchical structure as well as its fearsome efficiency out in the field.

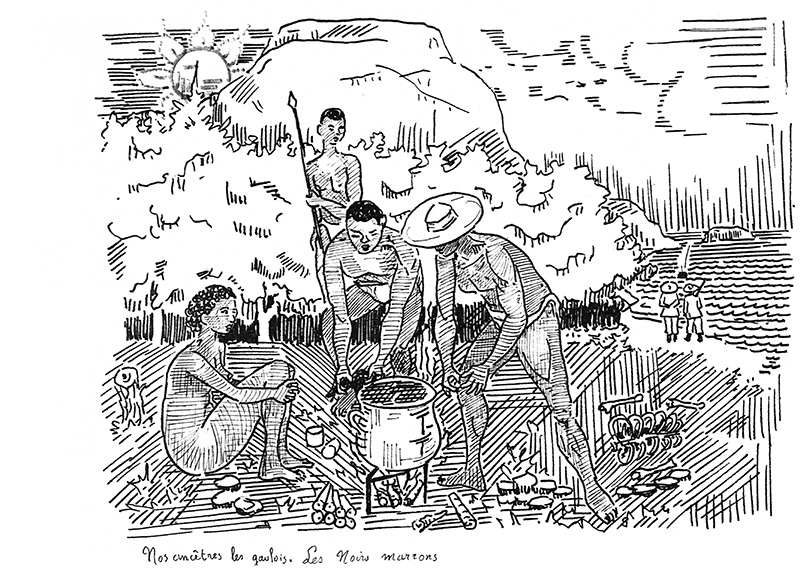

In ‘Les Marrons’ / Louis Timagène Houat, Paris, Ebrard, 1844.

Collection of the Reunion Departmental library.

Regarding the period of 1739-1765, the series of reports is coherent from the chronological point of view. There are certainly elements missing, but the documents give us a large amount of information and form a rich basis for study.

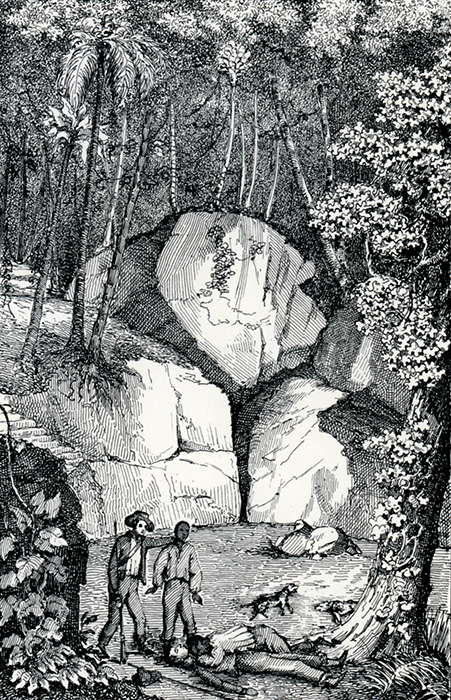

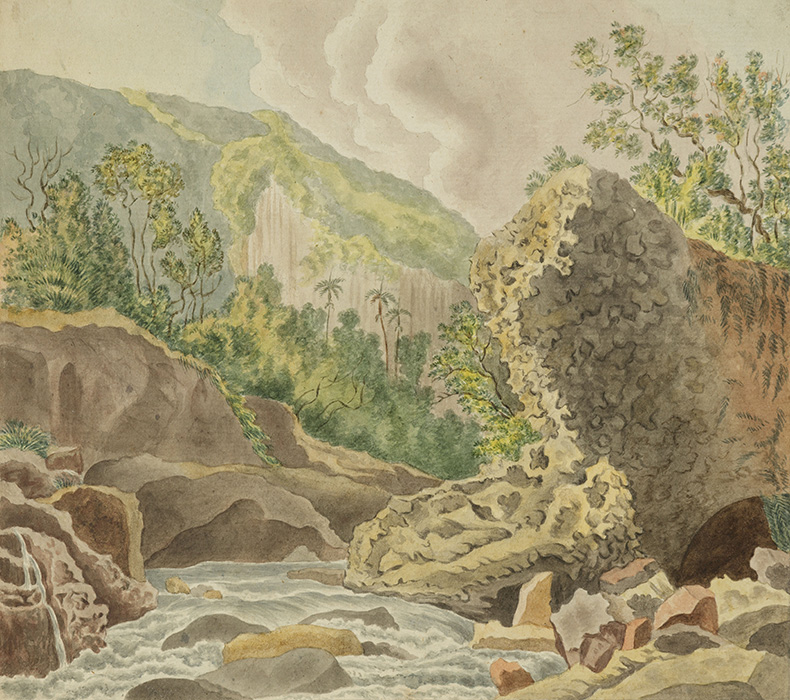

We learn that the beds of the island’s gullies were the points of entry to spaces occupied fugitive slaves. The different groups of maroons around the island mainly consisted of slaves traded in Madagascar. Despite the cultural and linguistic differences of the enslaved persons coming from different communities in Madagascar, they did share a common language which made it possible for them to construct the project of a maroon society, with political a political and military organisation that presented a threat to the colony. It was because the maroons exercised constant and violent military pressure, with the support of the feared Tafika Mainty (Black or secret army) that the governor during that period created the ‘detachments of slave hunters’, consisting of groups of settlers, since the colony lacked soldiers in sufficient numbers to be able to organise the defence.

Collection of Reunion Departmental archives.

As an example, the report submitted on 31st October 1751 following the return of François Mussard’s detachment mentions: In la Rivière Saint-Etienne, “the isolated plateau called Commencement L’islette à Corde (…) The above-mentioned Mussard asked the above-mentioned Grégoire, who was injured, if in the vicinity there were several other maroons and if they were the only ones of the group. He replied that there appeared to be two Camps on the other side of the plateau, one of which was precisely the one that the detachment had spotted and that they were heading for when they encountered the three blacks. There seemed to be 50 maroons, black men and women, as well as children and in the other camp, which was smaller and situated higher up, one league further away, there were 10 maroons, black men and women and children.(…) Mussard declared that in the camp in the question there appeared to be 30 huts made of logs, some of which appeared to house 3,4 or 6 blacks, as reported by Grégoire .(…) Following his long experience, Mussard, knowing that the maroons hide what they can of their spoils in caves and buried in the ground, had the camp and the surrounding area searched by the blacks following the detachment. They say that in a small cave, they found two guns in good condition and loaded with bullets and in the hollow of a tree a double-barrelled gun with bullets and about three handfuls of gunpowder in a case .

Detachment: François Grosset, Antoine Mussard, Gaspard Lautrec, Henry Hoareau, Sylvestre Grosset, Joseph Hoareau (father), Jacques Hoareau son of Noël, Louis Lauret, Antoine Cerveau, Claude Garnier.

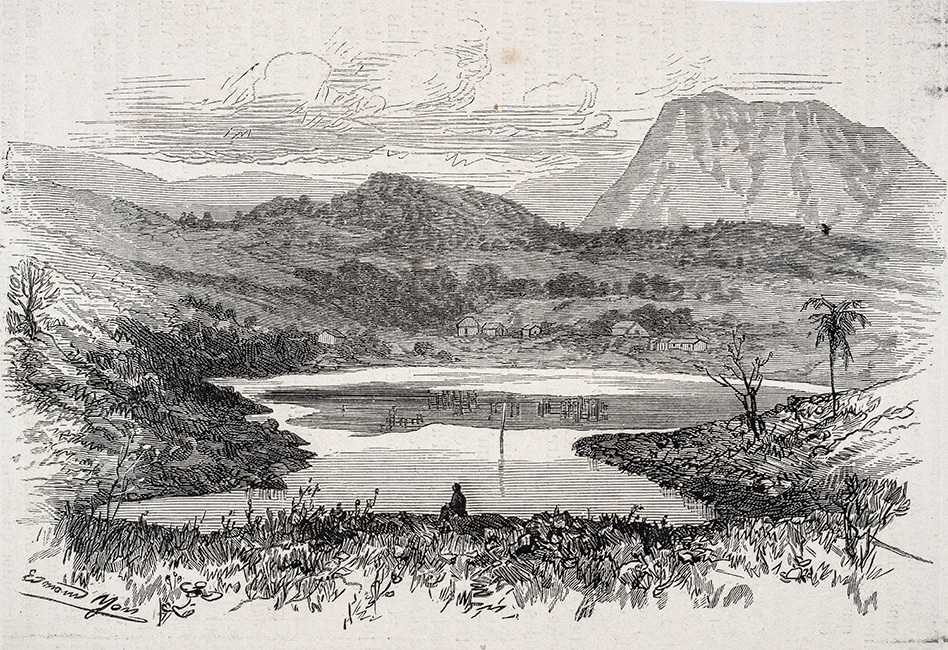

From reading these reports, drawn up after the return of the “hunt for long-term fugitives”, we learn that their villages were particularly well-organised. They housed a population of adults and children born free as maroons, referred to as “Créoles des bois” (wild Creoles), as well as a few old persons. Certain slaves preferring to commit suicide, “threw themselves off the cliff” to escape from their pursuers. The children were captured while their parents were killed during the fighting with the detachment. Some of these maroon camps sheltered a large number of individuals. They consisted of solidly constructed log huts, with tools, utensils for daily life, fields planted with maize, yams and other tubers, indicating settlement over a long-term. Some captives declared that they had been fugitives for about 20 years. Some had escaped from the Ile de France, lying 200 km off the coast of Bourbon island, in the hope of being able to sail to Madagascar more easily! They had set up camps they could retreat to in the event of attacks by militia.

The villages settled in the ‘ilets’, small sized plateaus resulting from erosion and generally close to a source of water, were sometimes protected by a fence of wooden stakes, and defended further down the slope by ditches filled with poisoned wooden stakes, their point hardened with fire. These traps, covered over with vegetation, were the source of serious injury for the hunters in the detachments . These small plateaus were an important element in the strategy adopted by the maroons: they would go from one to the other to flee the detachments of hunters and take advantage of a protected space, where they had stored reserves of food and hidden stocks of weapons. This network of ‘ilets’ was the object of the regular upkeep, aimed at maintaining this strategy. These small plateaus were linked up by paths consisting of gullies, hillside paths and narrow passes, all forming the archipelago of the Interior Kingdom. The maroons had dogs which would warn them of the approaching presence of any suspicious person and were capable of causing serious injury for the hunters.

The maroons’ situation necessarily involved a domestic structure and organisation propitious to an itinerant way of life, even though certain spots such as Ilet-à-Corde appear to have afforded permanent shelter to three generations of maroons, according to a 1752 detachment report. The toponymy was intended to respond to certain highly informative criteria .

Onomastics applied to maroonage developed in Reunion as from 2005 thanks to the work of Charlotte Rabesahala. Her research has made it possible to trace the words of enslaved persons through the toponymy and anthroponymy which are still applied today on the island’s maps, even though the spellings and pronunciation of these names have been modified over time to the extent that they have lost their original meaning .

The analysis and interpretation of the results of multidisciplinary research also make it possible to better identify and localise names originating in maroonage, whether these first originated in the language of the ‘detachments of slave-hunters’ or that of the maroons themselves. A space was thus created in the interior of the island – the Interior Kingdom – accessible solely to the initiated (the maroons), who would transmit orally the mental map of the mountain areas, enabling them to find their way, gather, protect themselves from the hunters and organise their life following death.

The study and comparison of all this information have finally made it possible to draw up a map of the island’s maroons in the 18th century, localising the settlements of long-term maroons as we know them. This map of maroonage contains the toponyms found in the documents, covering different periods. The names given by the maroons are of Madagascan origin and there are also French names given by slave-hunters .

For Charlotte Rabesahala, “the toponymy of the space occupied by the maroons offers a rich inventory of the resources of the territory, both regarding replenishing of food and other goods and guerrilla logistics and resistance. It maps out a true physical, moral and spiritual geography of the ‘Interior Kingdom’, made available to different groups and handed down from generation to generation”.

However, long-term maroonage came to an end when this territory became proportionally smaller with the extension of the area occupied by the settlers who, as from the start of the 19th century, gradually extended their properties into the island’s mountains, which saw the start of official settlement in the island’s three cirques. The rebellious character of maroonage was stifled, without really disappearing, however. Even though there is little information about this period to be found in documents, we know that groups of maroons continued their activity until the abolition of slavery in 1848.

The recent studies of the issue of maroonage in Reunion reveal essential information which still needs to be more thoroughly examined. Finally, we must take into consideration the fact the population now shows a strong desire to obtain more precise knowledge of maroonage as an act of resistance, giving it the important role it deserves to play in our local and national history.