Although slaves were denied legal individual status (combining legislation in Mainland France and local regulations), Bourbon law nevertheless recognised a type of humanity for slaves. Among other things, they were allowed to get married, to save their allowance and “to be educated in the Catholic, apostolic and Roman religion”. Moreover, the many procedures for emancipation, including repurchasing rights (made legal by the law of 18th July 1845), theoretically gave them the “same rights, privileges and immunities enjoyed by those who had been born free”.

Confirmed very early on also as ‘potential players’ in the context of repressive justice, the protagonists of slavery (whether defendants or plaintiffs) increased in number on Bourbon Island between 1723 and 1848.

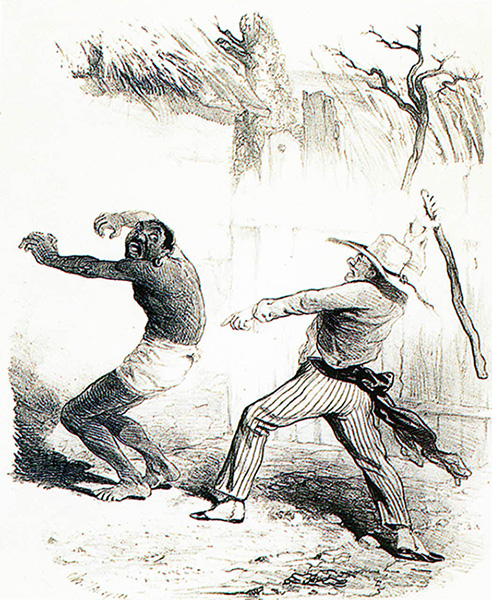

It was of course as defendants that slaves were first granted a status within this framework of repressive justice. With reference to philosophy or to the rights of ancient civilisations, public officials in Mainland France and colonists of Bourbon Island recognised the slaves’ capacity to discern right from wrong, or at least what they were prohibited from doing by their specific ‘institution’ which gave authorisation to what they could say or do. They therefore benefited from a form of free expression in their choice of words and gestures. However, this criminal responsibility of slaves was in no way antinomic with their status as an ‘object of property’, but rather intrinsic. Legislature was required to assimilate them partially and from time to time to be ‘subject to law’ in order to hold them responsible for their ‘inescapable’ opposition to the iniquitous status to which they were subjected.

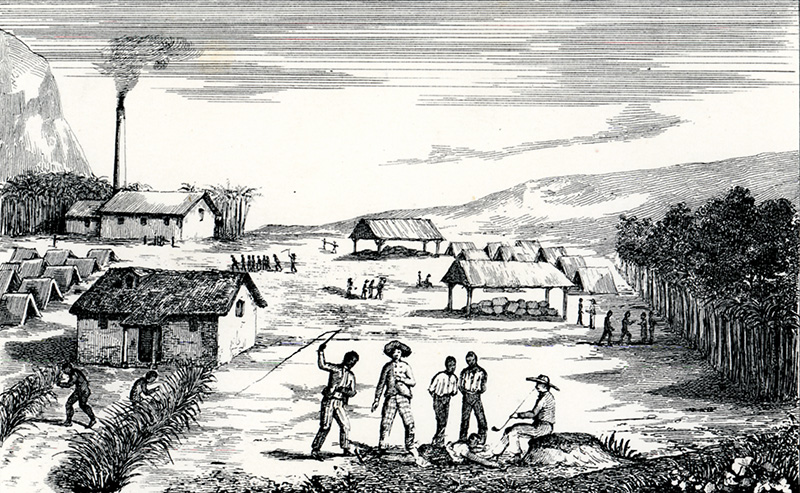

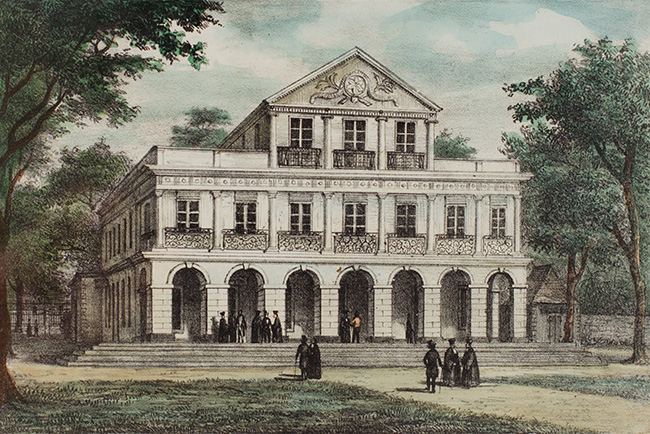

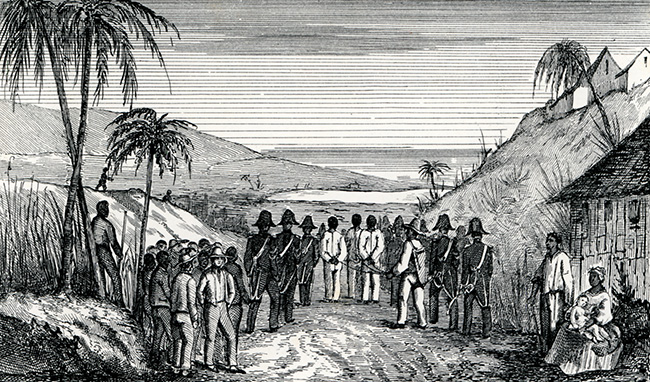

Advantaged by their ‘rights of possession’, slave-owners certainly always considered themselves as the only legitimate magistrates authorised to exercise repressive justice over their slaves. This coercive attribution of domestic sovereignty was all the more easily imposed in the early days of colonisation because most of the ‘Blacks’ were held on estates far from the capital where the only public court on Bourbon Island was located. Admittedly, public authorities never resigned themselves to completely abandoning their judicial prerogatives in the colonies. Articles 26 to 32 of the edict of December 1723 delegated to the Supreme Court the exclusive jurisdiction to rule on ‘heinous or serious crimes’ (as described by criminal law under the Ancien Régime) committed by slaves (homicides, robberies, rebellions, etc.). This reappropriation of the criminal justice system by the public authorities, which was disputed until 1848 by certain slave-owners, was in fact reaffirmed on several occasions by the rewriting or adoption of new normative texts on the subject, such as the local ordinance of 27th September, 1825.

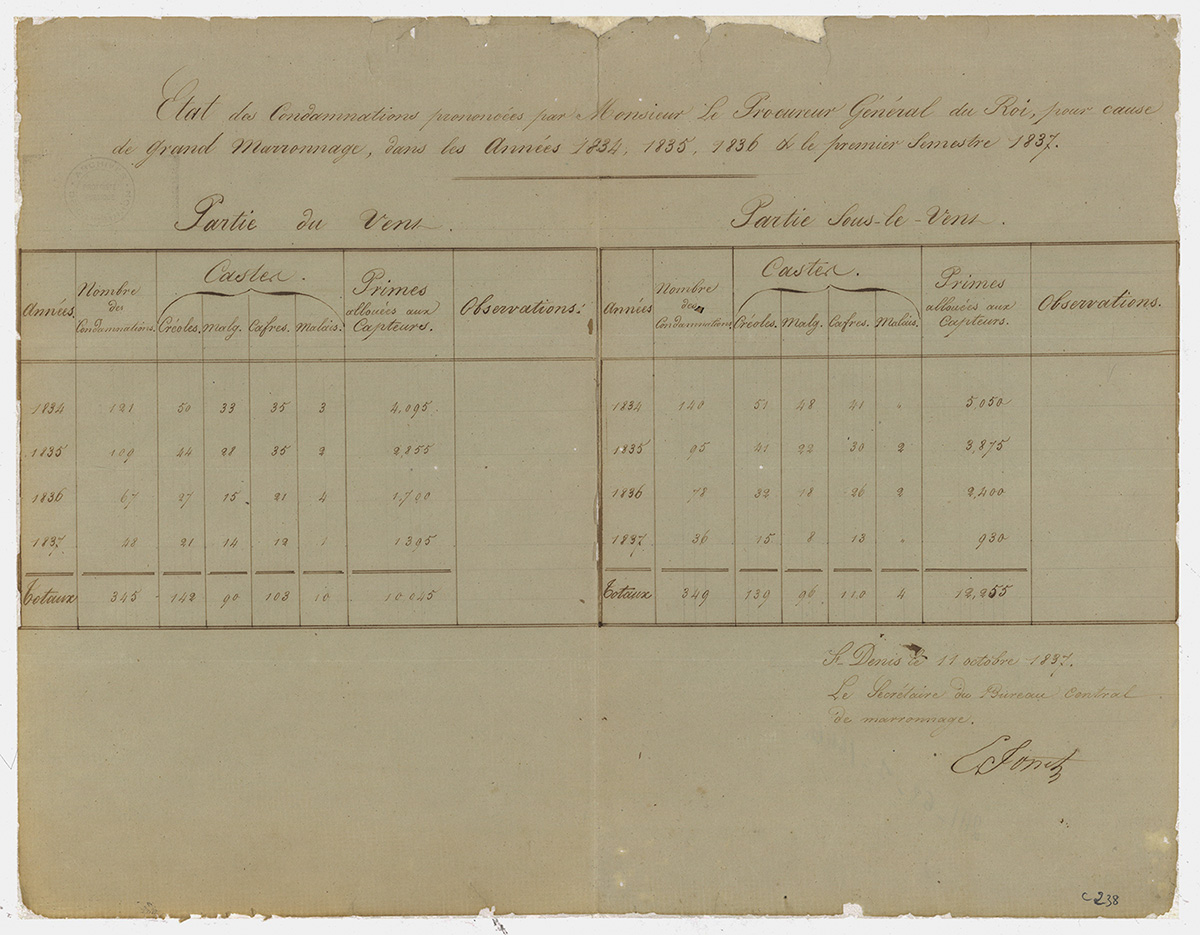

Although slaves were considered the ‘enemy within’ or ‘dangerous individuals’, they were not however subject to the same criminal law as free individuals. While theft, in all its nuances, was the subject of 22 articles in the penal code of 30th December 1827, this repressive law on slaves had only 4 articles relating to fraud, even though 11 normative texts were compiled. “Latitude granted to judges by the letters patent of 1723” in order to “describe the offences” was explicitly stated in article 3 of the local ordinance of 27th September, 1825. Moreover, certain offences were specifically reserved for them, such as assaults upon a free individual, especially when this concerned the master. In this respect, escaping for a period of more than one month was by far the most common offence committed by slaves (70% of offences judged under the July Monarchy) and the most repressed by the courts in Bourbon.

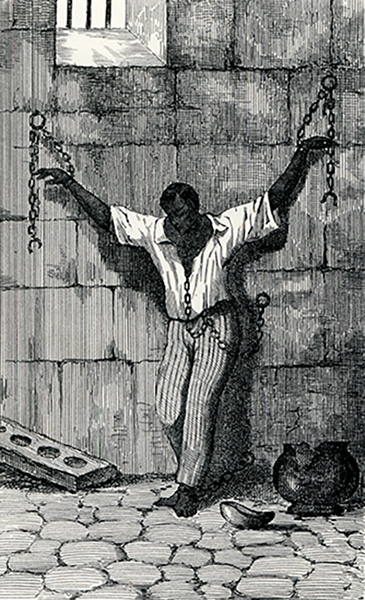

Sanctions drawn up for slaves were marked by the same concern for distinction and singling out. Originally focused exclusively on corporal punishment (mutilation, whipping, neck braces, etc.) or capital punishment (burning at the stake, hanging, the breaking wheel, etc.), these were gradually replaced (without completely disappearing from the repressive arsenal of Bourbon law) by prison sentences known as ‘chains’ or ‘irons’. As a matter of principle, slaves sentenced to a prison term did not have the freedom to come and go, but were forced to carry out forced labour ‘in the public interest’ and to wear an iron collar linked by a chain to other slaves. Contrary to criminal legislation for free individuals, the length of detention for each offence was not strictly limited to minimum and/or maximum periods for slaves. 45-year-old Elie, ‘cafre et noir de pioche’, a slave of Sieur Pajot, was sentenced on 27th February 1834 to one month in chains for stealing a hen. A few days later, Victor, a 25 year old Malagasy domestic servant, slave of Sieur Lartigue, was sentenced to 3 months in chains for stealing a duck! As the example suggests, the duration of sanctions varied according to the mitigating or aggravating circumstances attributed to the slaves by the magistrates but also depending on their ‘prejudices’ towards the servile masses.

Jean-Baptiste Louis Dumas. [1827-1830]. Drawing, pencil, watercolour, in colour.

Departmental Archives of Reunion Island Collection

Interrogations carried out between 1723 and 1848 by the judge’s lieutenants and then the examining magistrates shed light on the slaves’ ingenuity. Defendants would use a variety of tactics, swinging from measured submission to resolute protest, including all sorts of daring transactions in an effort to convince the courts of their version of events. In this way they hoped that their case would be dismissed during the investigation or they would be acquitted at trial, or at least benefit from a re-qualification of the facts or the recognition of mitigating circumstances in order to obtain a more lenient punishment. This made things harder for magistrates and assessors in cases that were much more complex than they appeared at first glance, which had been complicated by preliminary investigations or gross incompetence, let alone the statements by the slaves themselves.

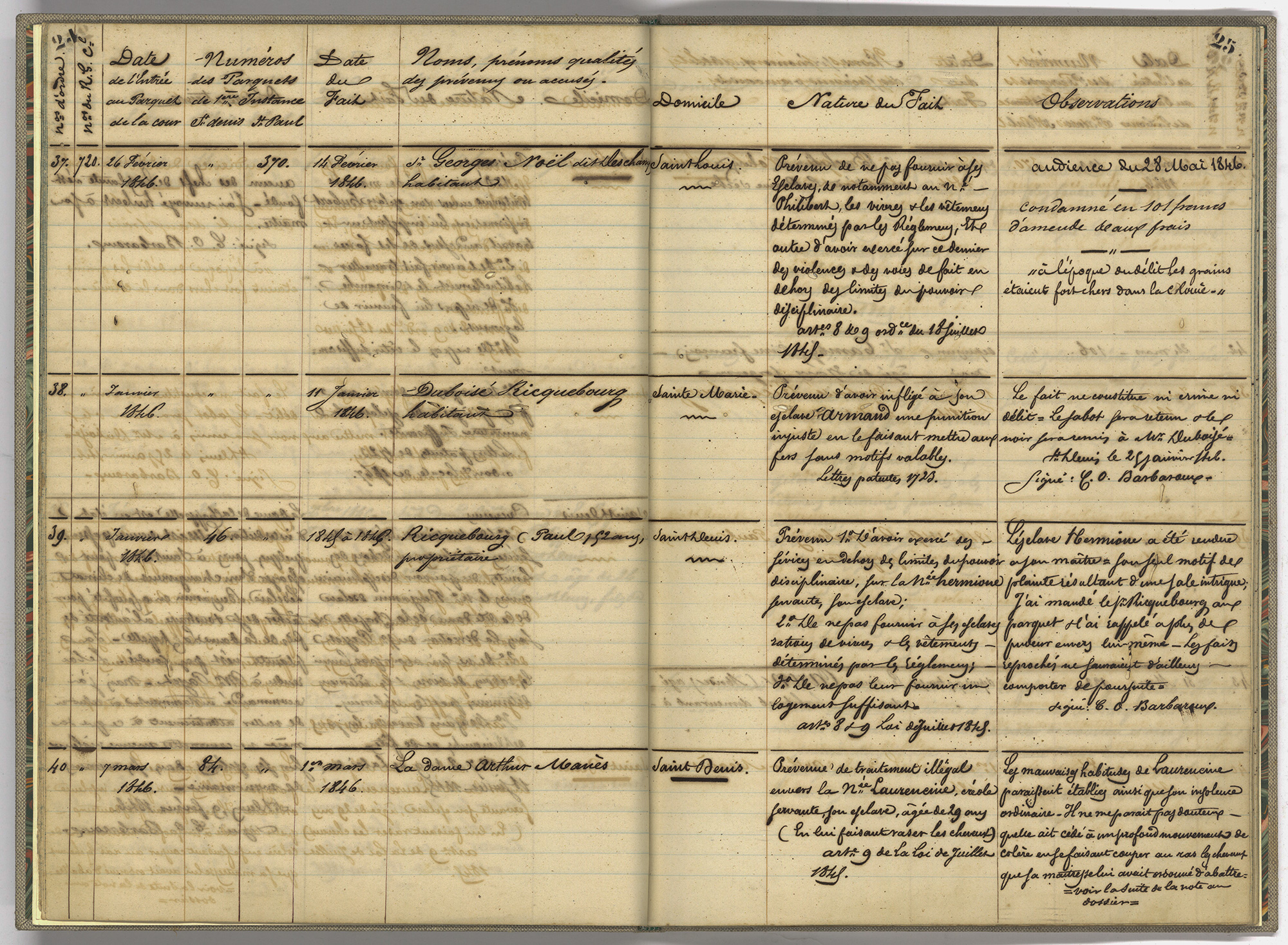

It was more complicated for slaves to have the status of ‘plaintiff’, to use the term of the criminal ordinance of 1670 or of criminal instruction of 1827. When victim of an offence, or even a crime, slaves could not legally bring a complaint against the known or presumed perpetrator before any judicial authority and start civil proceedings of his own accord. According to article 24 of the December 1723 edict, it was up to the master ‘to prosecute in criminal matters the reparation of outrages and excesses committed against their slaves’. More restorative than retributive, this repressive justice aimed less at recognising the moral and/or physical harm suffered by the victim than at compensating the owner for the destruction or degradation of his ‘property’ which had permanently or temporarily altered its condition. The death of a slave was simply the outright loss of the capital invested at the time of its acquisition and/or maintenance. Each day of inactivity of a convalescent victim represented a loss of expected profit on the work he or she should have done. On February 12th 1736, Sieur Dubois had to compensate Sieur Riquebourg with 200 pounds for drowning his slave, Louis, a 7 year-old Creole boy, excluding his parents (who were also slaves) from the proceedings. The same was true for Sieur Gerard, sentenced on 15th July 1828 to pay 30 piasters, not to Jean, the 30-year-old black farmhand who he had ‘violently corrected with a stick’ resulting in his incapacitation for 15 days, but to his master Leonard. It was therefore the potential productivity or the real value of the ‘property’ that magistrates would convert to monetary value during hearings.

Departmental Archives of Reunion Island Collection

Cases of slaves being physically abused by their own owners took on specific role in the colony. From early on, public authorities would regulate the disciplinary power of the masters over their slaves, at least on paper. Article 37 of the edict of December 1723 prohibited all kinds of mutilation or torture of ‘blacks’, specifically limiting masters to ‘chaining them or beating them with a rod’. However, legislators were aware of the trivialisation of brutality on the estates and the inherent cruelty of certain colonists, and granted slaves (under Article 19 of the same normative text) the right to ‘inform the public prosecutor’ or ‘entrust them with their memories’ of any ‘barbaric and inhuman crimes and treatment’ committed by their master. Sieur Bavière was undoubtedly one of the first slave-owners on Bourbon Island to be accused and sentenced by the public prosecutor’s office in 1734 for the murder of a black slave called ‘Philippe’, who had been the victim of ‘disproportionate discipline’.

In practice, this procedure was rarely applied in the colony. On one hand, slaves rarely mastered the intricacies of this particular legal procedure, such as the cross-checking of evidence to prove the offence. On the other hand, they could fear reprisals from their masters if ever their cases were dismissed during the investigation or thrown out at trial. Many magistrates working in the ordinary courts were themselves slave-owning colonists or people from Mainland France who were supporters of slavery. Finally, slaves could not really appropriate the right to ‘go to court’, but rather the right to refer the matter to the magistrate of the public prosecutor’s office of the competent court. The magistrate had the discretionary power to decide whether or not to initiate legal proceedings. In the second case, when faced with an impassive public prosecutor, victims could not bring a civil action before a judge’s lieutenant or an examining magistrate. Thus, between 1840 and 1843, only nine out of one hundred and four cases of this type were referred by the Bourbon Island public prosecutor’s office to a court of judgment.

The status of the slave as a plaintiff changed somewhat with the end of the Restoration and the July Monarchy. Articles 33 and 71 of the Criminal Investigation Code of 30th September 1827 respectively authorised the king’s prosecutor or the examining magistrate to ‘receive statements’ or ‘summon before him and hear’ all witnesses, including slaves, of all offences, including those concerning their own master. Article 23 of the edict of December 1723 had previously prohibited the testimony of ‘Blacks’ against their owners. In the absence of any material evidence or a confession from the accused, the testimony of slaves, particularly on estates isolated from the eyes of other free individuals, constituted indispensable evidence to prove the master’s guilt or innocence. Despite articles 156 (contraventions), 189 (misdemeanours) and 322 (crimes) such testimonies were only allowed during correctional or criminal trial hearings if the accused himself consented to it! In this case, however, procedure allowed the judicial authority to hear the slave’s testimony, admittedly without taking an oath, merely for ‘information’ purposes. The conviction of Sieur Riquebourg, on 9th October 1841, to a sentence of 5 years’ imprisonment and the prohibition of the right to own slaves for 10 years for ‘barbaric and inhuman treatment’ of his slaves is emblematic in this respect. When they testified, the determination and clear-sightedness of his victims (Estelle, Julie, Brigitte, Désiré and Pierre-Louis) clearly influenced the decision of the court in Saint-Denis.

However, the acquittals of Zénon Hibon on 23rd June 1842 by the correctional chamber of the royal court or of Casimir Gagnant on 9th January 1843 by the assize court of the windward district following acts of ‘excessive discipline’ and ‘serious abuse’ towards several of their slaves demonstrate the continuing collusion between magistrates and assessors of the ordinary courts and slave owners. Even after the enactment of the law of 18th July 1845 on Bourbon Island, which stipulated a sentence of two years’ imprisonment and a fine of up to three hundred francs for any masters found guilty of ‘abuse, violence or assault beyond disciplinary norms’ and a reshuffling of the assize courts, judicial decisions still remained rather favourable to the masters. Taken to court in Saint-Denis for four murders and various ‘barbaric and inhuman treatment’ of the slaves in the estate that he managed, Sieur Morette benefited from mitigating circumstances by the jury and was only sentenced on 16th January 1846 to one year’s imprisonment.