When sugar cane took the place of coffee as the island’s main crop, this led to important changes in the landscape and economy of the Madame Desbassayns’ estate, as well as in the daily lives of her slaves.

Both a place of residence and an agricultural exploitation, the Panon Desbassayns estate formed a small society where food was grown, animals raised and cash crops grown for export. Abbot Macquet, in his account of visits made there in the mid 1840s, describes it as a principality, with a chief and several ministers at its head .

The origin of the estate was a first plot assigned in 1698 to Thérèse Mollet, widow of Mr Duhal and Henri Paulin Panon Desbassayns’ maternal grandmother. It was located ‘above Saint-Gilles’, between the ravines of Saint-Gilles and L’Ermitage. This concession measured approximately half a mile in length and a quarter of a mile in width .

A number of conflicts arose between Thérèse Mollet and her neighbours, mentioned in the deed assigning the plot to her in 1727, which more precisely determined the limits and size of the property: 3,262 metres in length and 856 metres in width . It was not, however, rectangular and was located at an altitude of between 250 m and 500 m, above and at edge of the savannah grassland where, on 20th December 1731, a decree issued by the Higher Council of Bourbon island cancelled and prohibited all annexing and purchasing of land. The text stipulated that the grassland was to remain common to all landowners of neighbouring plots, to be used for grazing their animals .

It was here, on this plot, that were later constructed the mansion, the factory, the chapel and the first huts of the slave camp, the initial core around which the estate of Panon Desbassayns was created.

Upon her death in 1753, widow Duhal left equal parts of the estate to her two daughters. The first, the widow of André Rault , had six children and subdivided her plot into the the same number of sections. As for Augustin Panon (1694-1772), the husband of the second Duhal daughter, he divided his plot only between two of his sons: François Joseph Panon du Hazier and Henri Paulin Panon Desbassayns. The latter was named Debassayns because he inherited a plot located in the district of Trois-Bassins.

Like most of the settlers granted land above Saint-Gilles, widow Duhal did not live there, but used the land for growing crops . According to the poet and agronomist Auguste de Villèle (1858-1943), great-grandson of Madame Desbassayns , Augustin Panon was the first to settle there, in a timber house. As from 1780, his son, Henri Paulin Panon Desbassayns, purchased the plots belonging to his brother Panon du Hazier’s children, then a few plots belonging to André Rault’s heirs. By the time of his death in 1800, he had more than doubled the area he had originally inherited.

When she was widowed, Hombeline Gonneau Montbrun, from then on more commonly known as Madame Desbassayns, continued to expand the estate. On her death in 1846, the latter covered an area of 378 hectares . The area available for growing crops covered approximately 300 hectares and the 500 hectares of savannah grassland had not yet been annexed.

In addition to this estate in Saint-Gilles, Madame Desbassayns owned another, 3km away as the crow flies, located between the river beds of Divon and Bernica , at an altitude of 500m at its lowest level, an estate she inherited from her father Julien Gonneau Montbrun when he died in 1801.

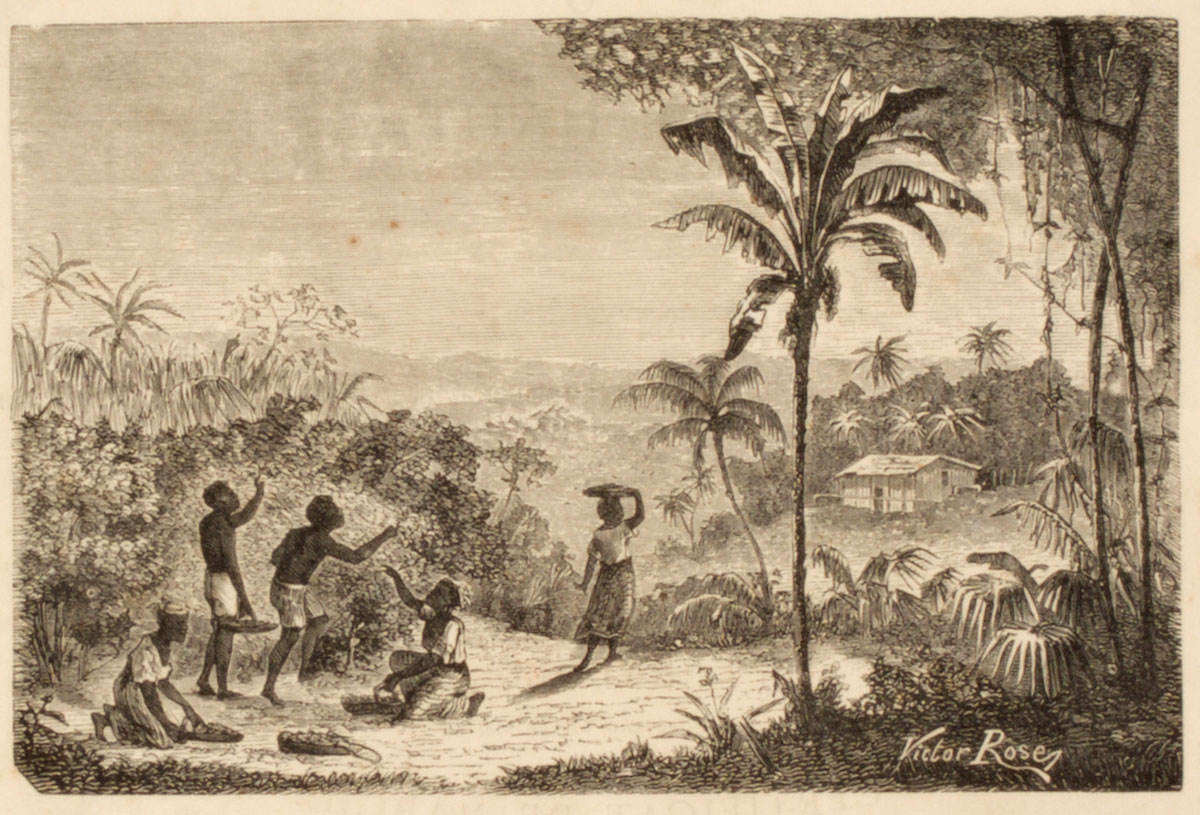

The 18th century was an intense period for the growing of coffee in the district around Saint-Gilles. The mansion, the construction of which was completed in 1788, had a roof terrace where coffee was laid out to dry after harvesting. According to Auguste de Villèle, the growing of cotton, the seeds of which Henri Paulin had brought back from India, “competed with that of coffee and food (crops). ” However, there is no longer any record of cotton production in the 1823 statistics . In 1815, it already covered just 7 hectares, compared to 27 for coffee and 250 for maize .

In 1817, the traveller Auguste Billiard, living in a house neighbouring that of Madame Desbassayns, in his book mentioned the destruction of most of the island’s coffee plants, following the cyclones and period of drought of 1806. In his opinion, many of the settlers abandoned the crop because they could not wait the four to seven years needed for the young plants to achieve maturity. Lieutenant Frappaz, on the other hand, put the decline of coffee down to a steady decrease in rainfall, rather than to exceptional climatic events, declaring that the rain was seen to “fall along the upper forests neighbouring (the) lovely plantation” .

This probably explains why the estate of Bernica, located at a rather cooler and more humid altitude, was chosen for the first experiments in growing sugar cane and the construction of a sugar factory.

It was the estate of Saint-Gilles, however, that became the object of Madame Desbassayns’ attentions. She entrusted its management to her son Charles, through an agreement signed in 1822 . One of the main assets of the estate was its short distance from the coast, where Madame Desbassayns set up her warehouses. In 1829, she had a road laid down between these and her factory, the location of which corresponds to the current road known as Chemin Carrosse.

However, the estate was not dedicated solely to monoculture of a crop for export. In 1805, long before the damage caused to the coffee plants by the extreme climate events occurring in 1806-1807, food crops (maize, wheat, vegetables and potatoes) already covered 85% of the agricultural land, compared to just 15% for coffee .

In 1846, when sugar cane was thriving, the latter covered over 34% of the agricultural land, compared to approximately 61% for food crops . Maize alone ranked first, with 118 ha, representing close to 50% of the acreage sown, way ahead of the various vegetable crops (8,3%) and cassava (4,5%). The latter thus did not replace maize as the staple food for the slaves and animals, despite the recommendations made by Joseph Desbassayns and the instructions issued by his brother Charles .

The development of sugar cane thus appears to have depended on the presence of an abundant work force, with a large proportion of the agricultural land devoted to feeding the latter. Concerning this issue, we can quote a comment made by one of Madame Desbassayns’ grandsons, who noted that his grandmother’s views concerning the economy of the estate differed from, even conflicted with, those of her son Charles. She was convinced that sugar cane impoverished the soil and, since it required plantation owners to invest and therefore run up debts, would lead to their downfall . By favouring the continued production of food crops, she wished to ensure and guarantee food production for her many slaves, as well as ensuring the self-sufficiency of the estate.

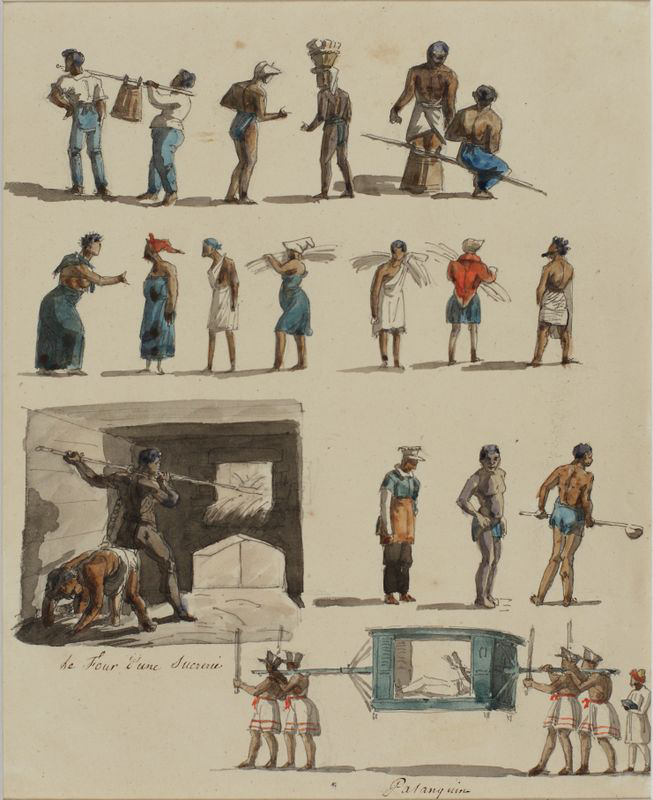

The slaves were supervised by a bailiff, responsible for making sure they carried out their daily tasks, defined by the employers, as well as applying the methods set out by the latter. Working under his orders was a whole battalion of guards and overseers. Charles Desbassayns had written out Instructions (‘Notes’) in the form of a catalogue of observations and recommendations regarding each of the guards, overseers and group leaders, specifically named, with the aim of achieving maximum productivity from the servile work force .

The group leaders, referred to as overseers (‘commandeurs’) occupied the highest rank possible for a slave to achieve. Their function consisted in commanding a group assigned to an activity or a clearly defined place, in the fields, the factory, the main house on the estate, or in the garden, to cut wood in the forest or collect coral on the coast.

Those in charge of the chicken coop, the purifying vats in the factory, or of the teams of carpenters or sugar-cane labourers were given the title of ‘chief’ . The overseers, men or women, were chosen through their capacity to be feared, but also for their competence in their field and for other qualities, notably skill and intelligence. Total submission was required of them, though Charles Desbassayns was forced to note that his instructions were not always carried out exactly and sometimes even noted a degree of complicity between his chiefs and those disobeying. He thus asked the bailiff to increase the number of random controls, to frequently switch the guards responsible for each task and, if necessary, to demote them .

Like the overseers, the guards were selected among those the master could trust. In Madame Desbassayns’ will, drawn up in 1845, 23 were listed, of whom 10 or so were aged over 60. Contrary to what one might think, it was not an easy position, since every evening they had to give an account to the bailiff of everything accomplished or observed. The role of the guards on the estate was not simply to protect the fields from thieves. They also had to carry out a number of tasks, such as pruning trees, uprooting weeds, harvesting maize or making rope out of aloe fibre, known here as ‘choca’ (yucca) or ‘cadère’. The women most often occupied posts in the yard or close to the main house. The woman in charge of guarding the hospital, who was also the nurse, took care of the patients and supervised their work, which included the manufacture of sacks for packaging, using ‘pandanus’ (screwpine) leaves.

Whippings, mentioned in Charles Desbassayns’ ‘Instructions’, were among the punishments meted out to guards as well as overseers.

In 1845, those referred to as ‘Noirs’ or ‘Négresses de pioche’ – common labourers – accounted for close to 48% of the slaves with a defined role. They thus by far represented the majority of the workers. Taken literally, the word ‘pioche’ means ‘pickaxe’ and refers exclusively to those working in the fields. According to Madame Desbassayns’ will (1845), there therefore remained only three workers and a single cart driver to work the factory and take care of all the transport. The will also mentions 16 mules and 39 oxen with their carts. In addition of the large number of guards, (12,5% of the slaves), there were many domestic workers (10,5%) and also masons and carpenters (8,5%).

As regards the number of workers and cart drivers, the extremely small number of them indicates that specialisation only concerned a limited number of workers. Since agriculture and sugar production were seasonal activities, a rational management of the work force required the latter to be adaptable, in order to transfer quickly and efficiently from one crop to another, from the field to the factory, from production to maintenance. This was in accordance with Charles Desbassayns’ instructions, recommending training slaves to carry out several tasks . The majority of the common labourers (Noirs de Pioche), formed a category that was social rather than professional, making up the lowest ranks of the slave community.

In his ‘Instructions’, Charles Desbassayns declared that Africans would only work correctly if they were permanently supervised. He considered that the solution to the problem was to set up a strict organisation based on constant mutual supervision, random and repeated controls, various forms of punishment, from whippings to prison, as well as working on Sundays and being forbidden from leaving the estate. Since he could not keep an eye on or take care of everything, the bailiff had to ‘create eyes and legs everywhere, a substitute spirit and memory’ , with each being constantly on the alert.

No oversight or failure to respect the regulations was to be tolerated by the bailiff. Charles Desbassayns thus appears as a cold and methodical company director, whose main concern was to get the most out of a submissive and totally exploited work force.

With such practices, the atmosphere reigning over the whole of the estate could not be other than tense and social relations conflictual, since based on mutual fear and mistrust. However, the bailiff was also instructed not to be too harsh with slaves deserting for just a few days, instead of placing them in irons or locking them up for too long a period , since they needed to recover their strength and courage. He considered that over severe practices could spark off a cycle of revolt, escape and harsher and harsher and harsher punishments.

There remains no detailed description of how Madame Desbassayns’ slaves were housed. Like those of the indentured workers who replaced them after 1848, their huts were constructed using materials present on the estate: various tree trunks and branches and vetiver leaves, sugar-cane straw and long grasses from the area of savannah grassland for the roof. For clothes, the only thing we know is that they were dressed ‘well enough for the mild climate of Bourbon island’ .

Their huts were mainly used to shelter them when asleep after the long exhausting days’ labour. Each morning, when the bell rang, with the exception of two guards, they would leave the camp and gather in groups to go to their place of work. According to Abbot Macquet , the discipline was virtually military. The children were looked after by a domestic slave (‘Négresse de cour’) who, in charge of the joyful group, also had to sweep all around the mansion and make sure the area around the factory was kept clean. As for the wet-nurses, they were employed in manufacture, making sacks for packaging.

No-one was allowed into the camp during the day and the slaves had to wait until all the groups returned before going back into the huts, once each guard, supervisor of commander had transmitted his day’s report to the bailiff.

Charles Desbassayns’ Instructions also indicate that the slaves’ meals, both for adults and children, lunch and evening meal, were prepared collectively in a slaves’ kitchen located in the yard of the main house on the estate. The adults’ rations were taken out to their place of work, where they were distributed by those in charge of the work groups. “On Sundays, they were given to the Africans in person” .

The only time the slaves were allowed some rest was Sunday afternoon. All morning, until one o’clock, they had to carry out chores consisting in cleaning, mainly the factory, but also the other agricultural buildings. For Charles Desbassayns “this day of scrubbing and cleaning” contributed to keeping up their interest, attachment and even passion for their work. On that day, if potatoes had been harvested, they were allowed to go and gather any that had been left behind, leaving the field clean once they finished. Presented as a favour granted to them, this was, in fact, a way of making them clean the fields to prepare them for sowing once again.

The terms used by Abbot Macquet when describing the slaves departure from the camp in the morning give the impression of them as being a human herd, divided up into groups taken to their place of work each day, under threat of their overseer . In fact, more than one third of the slaves living in the camp had a family life. Madame Desbassayns’ will lists fifty or so households, sometimes with several children, representing a total of 25% of the slave population. Men and women of over 16 were greatly in the majority (69%), but with quite a large number being over 60 (9%). If we also count the 28 slaves described as being sick, weak or infirm, that gives a fairly large proportion of totally or partly non-productive workers on the estate. Consequently, each slave was given an occupation adapted to his or her age and physical condition.

Slave couples on the estate were united by religion and the children born were given the sacrament of baptism . These marriages became more common after 1843, the year the Chapelle Pointue chapel was constructed .

Decided and organised by Madame Desbassayns, these religious ceremonies presented her with the opportunity to give her slaves French names. Through her attempts to give them a sense of family and its values, she almost certainly wished to instil in them an attachment to the estate and its masters. In a letter dated 4th October 1821 addressed to her son Charles, she expressed her fear of seeing them mistreated by inexperienced white managers . In this respect, she applied the same objectives as her son Charles , if less brutally, these being productivity and the cost-effectiveness of the estate, as well as the long-term existence of her business, on the eve of the abolition of the system of slavery.

Madame Desbassayns died in 1846, two years before that event so greatly feared by the masters. Her grandson and successor Frédéric de Villèle seemed to share her concerns: in November 1848, he freed six former slaves trusted by his grandmother, including five overseers, making them his own personal guards . Through this double promotion, he undoubtedly wished to build up a personal retinue of reliable and skilled persons to oversee the future free workers, thus guaranteeing a degree of continuity in the workings of the economy of the plantation.