On Bourbon island as from 1674, article XX of the ordinance issued by Jacob Blanquet de La Haye, viceroy, admiral and lieutenant for the French King in all of India, clearly prohibited mixed marriages: “Deffense aux François d’épouser des négresses, cela dégoûterait du service, et deffense aux noirs d’épouser des blanches, c’est une confusion à éviter” (“It is forbidden for Frenchmen to marry black women, as this would distract from their service and it is forbidden for Africans to marry white women: it is a confusion that must be avoided.”)

This legislation, not applied in the early years of settlement of the colony, was later reinforced when cash-crops replaced subsistence farming on the island. In 1723, the letters patent, issued in the form of an edict, institutionalised the Code Noir (Black Code) in the Mascareignes islands, reinforcing this prohibition and even applying it to unmarried couples, with anyone not complying liable to fines and permanent deprivation of liberty for them and for the children concerned (article V). Slavery created an imbalance in relations between groups being set up and led to changes both in people’s minds and their customs

Marriage remained a founding element of the family. It thus had to be above all reasonable and required the consent of persons of authority: parents et administrators. The island, on the basis of its original settlement, essentially consisting of male bachelors but in the space of one or two generations became a less imbalanced society, copying the family model left behind in France. Love played a secondary role in these associations, which rather than being associations of two young persons, were associations of two families, whose aim was to perpetuate a lineage and a heritage. Some, however, decided that their union was not a duty but a deep attraction, overturning the social codes, even if the other, forbidden and foreign, became a source of danger in that he or she shifted the frontiers of the uniform and all-powerful world of the Whites that could not surrender to the world of the Blacks, (pre)destined to be servile. The ‘confusions’ and ‘disorders’, constantly reiterated in the ordinances, were not always avoided.

The question of mixed-race unions was a complex notion in this society that called itself plural. Until the 1960s, the mixed origins of the first settlers were largely understated. We must not forget that in Saint-Paul in 1815, the religious, civil and judicial authorities together organised public destruction of the ‘red book’ written by Father Davelu, through fear of revelations of inter-ethnic relations, or that later on Count de Villèle, minister under Charles X, asked for the Antoine Boucher’s monograph about the first Reunionese families to be kept secret (1826-1828), and that finally in 1941, the archivist Albert Lougnon was unable to assume the ‘rare indiscretions’ in the same monograph concerning the island’s respectable families.

We can, however, question and assess the true rifts existing within this colonial society, as well as the solidity of the frontiers between the free and the servile populations. The objective is to pinpoint these ‘invisible’ families who took no heed of prohibitions (children and partners having no lineage, patronymic or official alliance) and study the strategies they adopted to protect themselves. Mixed couples, even more than others, made use of notarial deeds. They would distort, to their advantage, all the legal documents: emancipations, declarations of births, legal recognitions, adoptions, parental declarations, donations, sales, wills etc. All these deeds recorded actions that were prohibited between Whites and slaves could become the object of opposition, contestation and even legal procedures.

To examine these different processes, we will take the example of one family, that of Florentine.

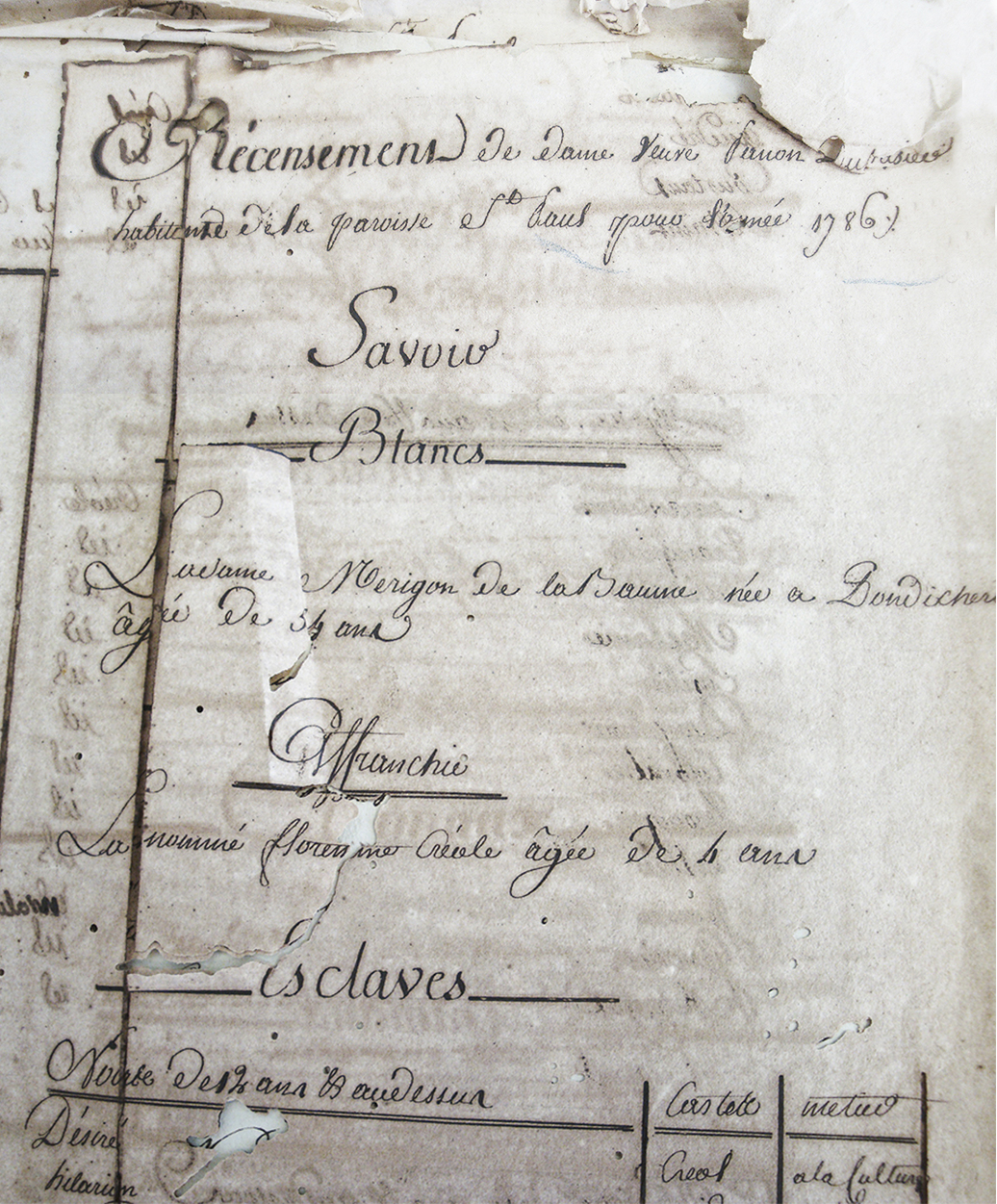

The little girl was four years old when a rich Creole woman, Dame Charlotte Mérigon de La Beaume, widow of Joseph Panon du Hazier, was listed in the 1786 census.

She was recorded as an emancipated Creole. An assembly of friends gathered on 30th July 1787, to request for her to be come under a legal guardian and “in the absence of parents, friends” would be responsible for protecting the child. Mr Panon was appointed her ad hoc tutor, which resulted in her receiving the donation made by his mother, the widow Panon Duhazier, so that the four-year-old girl could be emancipated, which was granted by the administrators of the colony on 28th December.

However, the little girl did have a family, who identified themselves in 1792 when summoned by her biological mother, Ursule, through a different assembly. Seven emancipated slaves were then gathered, including her maternal grandfather, as well as the little girl’s cousin. A family of emancipated slaves, who until then had remained unknown, came to take responsibility of the child upon the death of her protector. We learn through this deed of an action carried out by Madame Desbassayns, widow of (Henry Paulin) Panon who: “judging that there is little hope for the life of Dame Panon Duhazier”, sent Florentine back to her biological mother Ursule, an emancipated slave. The parents, non-existent in 1787 and appearing in 1792 (which leads us to doubt the reliable character of these documents), appropriated for themselves the future of Florentine when she was banished from the home of her godmother on the day the latter was dying. They decided to entrust her guardianship to her mother, since she was “of irreproachable behaviour”, a necessary condition.

While Florentine returned to her original environment in her slave family, a necessarily brutal event, she married at the age of 27, with the approval of her protector’s children and surrounded by white settlers, who had brought her up in her early childhood. Neither her father nor her mother were present at the time, nor were they present at the civil ceremony in the town hall of Saint-Denis, or when she signed her marriage contract, made official by the notary Carré at the home of her godfather Reynaud de Belleville, her protector’s son-in-law. Her father, Jean Baptiste Véronge de Lanux, a white Creole, remained secret, only revealing his identity several years later. The two worlds were kept apart and each event concerned a different community, making it impossible for relatives and friends to mix. For the sake of the civil status, Flore, also called Florentine was the “natural daughter, of age, of Ursule, a slave emancipated by Mr Véronge”, which is officially false, and since Ursule was emancipated in 1787 by Michel Lebrun, a new arrival from Alsace, who gave her as a means of subsistence a plot of fallow land in Laleu, as well as three slaves.

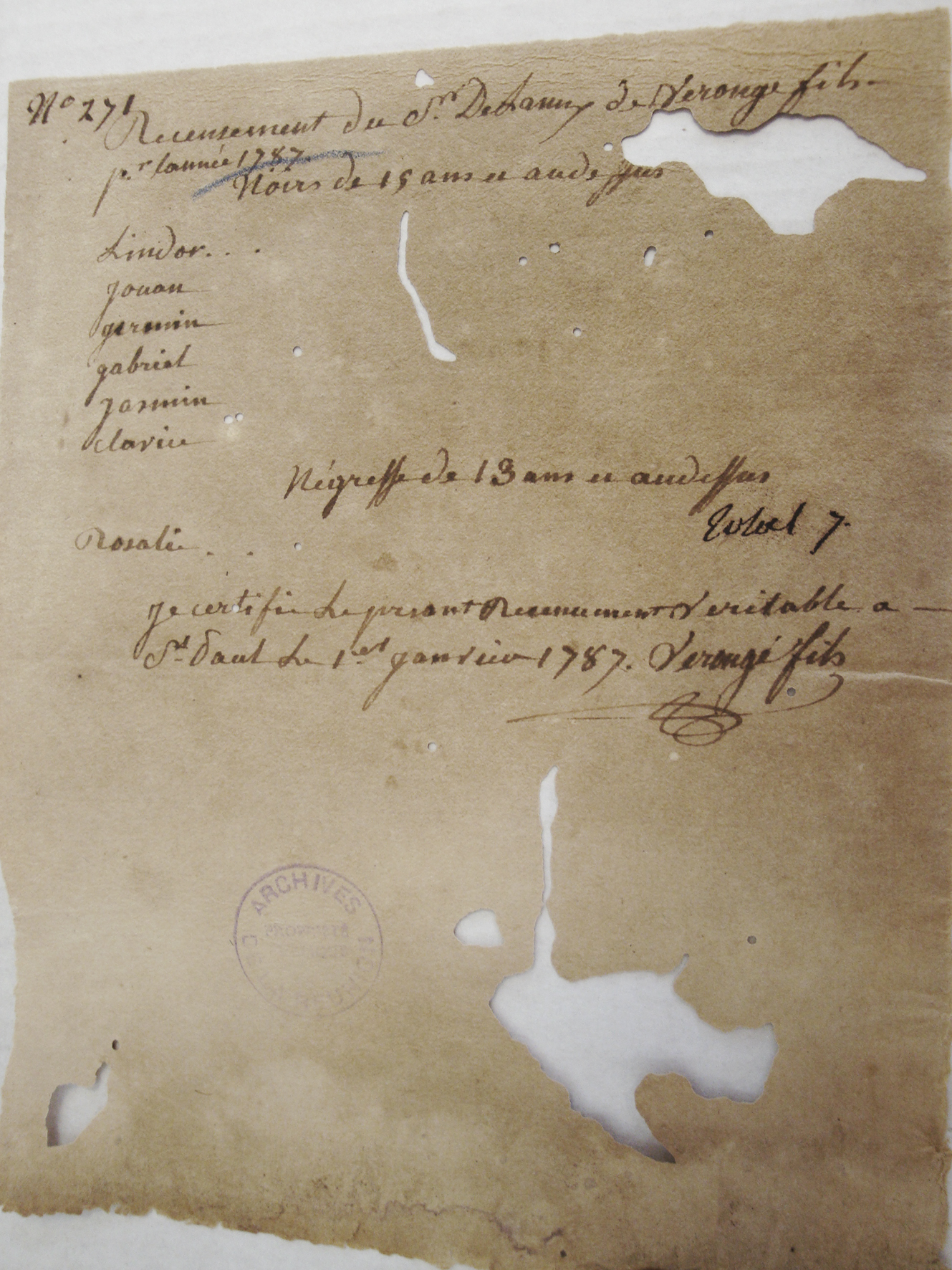

These three slaves had the same first names as those listed under Véronge de Lanux in the 1786 census: Jouan, Jasmin and Rosalie. So, there was indeed a fake purchase between Véronge and a fictional person to facilitate the emancipation of Ursule, which might have been refused for moral reasons.

Fictional sales were frequently used by mixed-race families and became heritage constructions both for their concubines and their children. Most of the time, these were carried out through a nominee to whom the master initially sold property, which the nominee then had to sell to his concubine or her children. Following donations of emancipations, which were compulsory and legal, later donations between masters and their slaves were reprehensible: article 51 of the Code Noir (1723 edict) stipulates that donations and legacies in favour of emancipated slaves were prohibited. In the colonial society, the notion of property of whites going to enrich persons of colour was simply not admitted. The master living with a concubine was, through the donations he made to his emancipated slave and her children, guilty of disinheriting his legitimate official family, as well as destabilising the established economic order. For these unofficial families, one of the main problems was transmission of heritage, which was why Véronge de Lanux, who attempted to ‘create a family’ with his concubine Ursule, resorted to donations presented as sales of his property.

He thus wished to make a donation to his daughter Florentine, since in 1808 he conveniently sold her a plot of land that she declared as being her dowry for her marriage to take place the following year. He committed himself not only to providing her with two Africans, but also to having a wooden house built for her, as well as a small shop and also to working the land and surveying the houses and the productions by his own trusted Africans, while handing over to her all the profits until she could do so herself. The proposition was particularly exceptional and generous. While Jean-Baptiste Véronge de Lanux was not able to emancipate his daughter Florentine, undoubtedly due to her young age (19), as well as the opposition of his parents and/or the notables of the town of de Saint Paul, he nevertheless later acted as a loving father, attentive to her future.

At various points in time, Véronge acted as guarantor for Ursule, both when Ursule transferred to Florentine her ‘tutorship’, and during her acquisitions, which he also did for the purchase made by his son Pierre. In fact, simple emancipated slaves could be suspected of having insufficient means for such purchases. He thus continued to carry out sales for his concubine and in 1828 Ursule actually sold four plots of land acquired from Véronge de Lanux, that Ursule sold on in 1828. The stakes behind these fictional sales were high, since it was a case of protecting his illegitimate family.

With these transactions, carried out at his home, little by little, the master sold off his property in favour of his concubine and their children. These various sales reflect the stability of their union. There was indeed a transfer of property from the owner to his concubine and their children. These families created efficient means of overcoming the prohibitions, even though these were sometimes complicated and tiresome. To do so they applied their own logic to the applicable laws.

While transmission of material heritage was important, so was symbolic heritage. The Code Noir excluded the mixed-race family from the normal process, by forbidding marriage, and also excluded natural half-cast children. Onomastic separation went hand-in-hand with legal and social segregation.

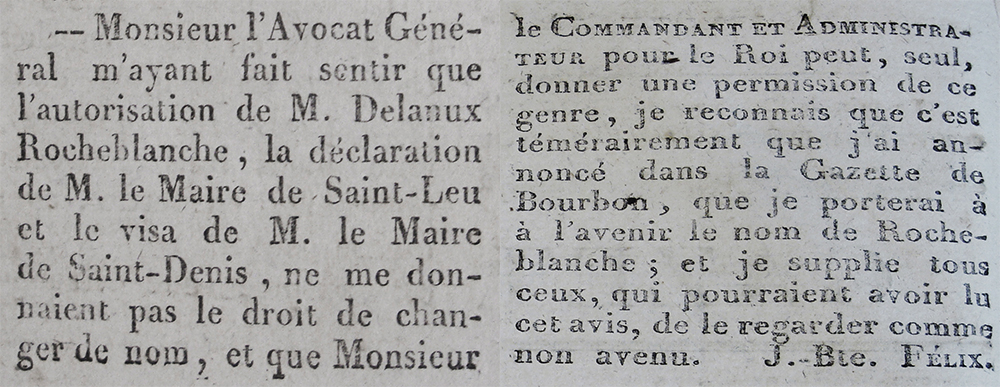

The issue was particularly painful for one of Florentine’s brothers, Jean-Baptiste Félix, who had no more rights to use the nickname of Rocheblanche than he had to use the family name of Véronge de Lanux. In March 1819, he published an apology in the newspaper Gazette de Bourbon. He seemed to accept the customs of the time, even apologising for having had the ‘foolhardiness’ to use the nickname of Rocheblanche.

He did not forget his origins, but he later struggled to have his rights recognised, as well as those of his children, to whom, being unable to give them the surname, he gave Rocheblanche as a first name (1825, 1830). Jean Baptiste Félix went beyond capacity of the society to become integrated into the class of white settlers. The word he used is interesting in that it reflects a highly appropriate, almost impertinent, tone. Made legitimate by his father on 12th April 1831, at the age of 40, his audaciousness was rewarded. Two weeks later, on 1st May, his tenacity, or his joy, enabled him to give his son the first name of ‘citoyen démocrate’ (democratic citizen). He was finally recognised as a fully-fledged citizen, as was his son. Through a ruling dated 7th December 1840, that is to say ten years later, the civil status registers were rectified with the addition of the father’s name Véronge de Lanux, for his son Grégoire Marc Félix Rocheblanche, recorded in the registers in February 1830. Ten years after being made legitimate, through the marriage of his parents, he still had to fight to give his family name to his descendants.

In 1831, when marriage between the free population and emancipated slaves finally became possible, Ursule and Jean Baptiste Véronge de Lanux made official their union, at the age of 67 and 70. They had spent close to 50 years living together, in spite of the laws and the society. Their marriage contract was drawn up by the notary Gédéon Choppy on 5th April 1831, at the bride’s residence. The latter had entire freedom to manage her estates and her income. As for the groom, he declared having no estate, and we should add, no demands. Their marriage contract was a total transgression of the society’s customs, as was their relationship. During the civil ceremony, their 14 children, at the time aged between 47 and 26, were made legitimate. Four of their daughters married (late in their lives) newly arrived European settlers and their other children married ‘free coloureds’

While this relationship was, in fine, finally recognised, this did not come without a price. Ursule had to abandon “her maternal friendships” for Florentine in 1787, even though she showed (or was compelled to show) gratitude towards Charlotte Mérigon de La Beaume. It is highly likely that the initial violent reaction of Madame Desbassayns towards Florentine was later tempered by the children of the protecting godmother, who continued to take care of her during her marriage, while continuing to exclude her biological father. The latter, coming from an important family on Bourbon island, remained under the control of his society, which constrained him by its codes, its prohibitions and its hypocrisies.

Being in love, however, and being young, he took risks to stabilise his illegitimate family and shake off the prejudices of the social group of his origins.