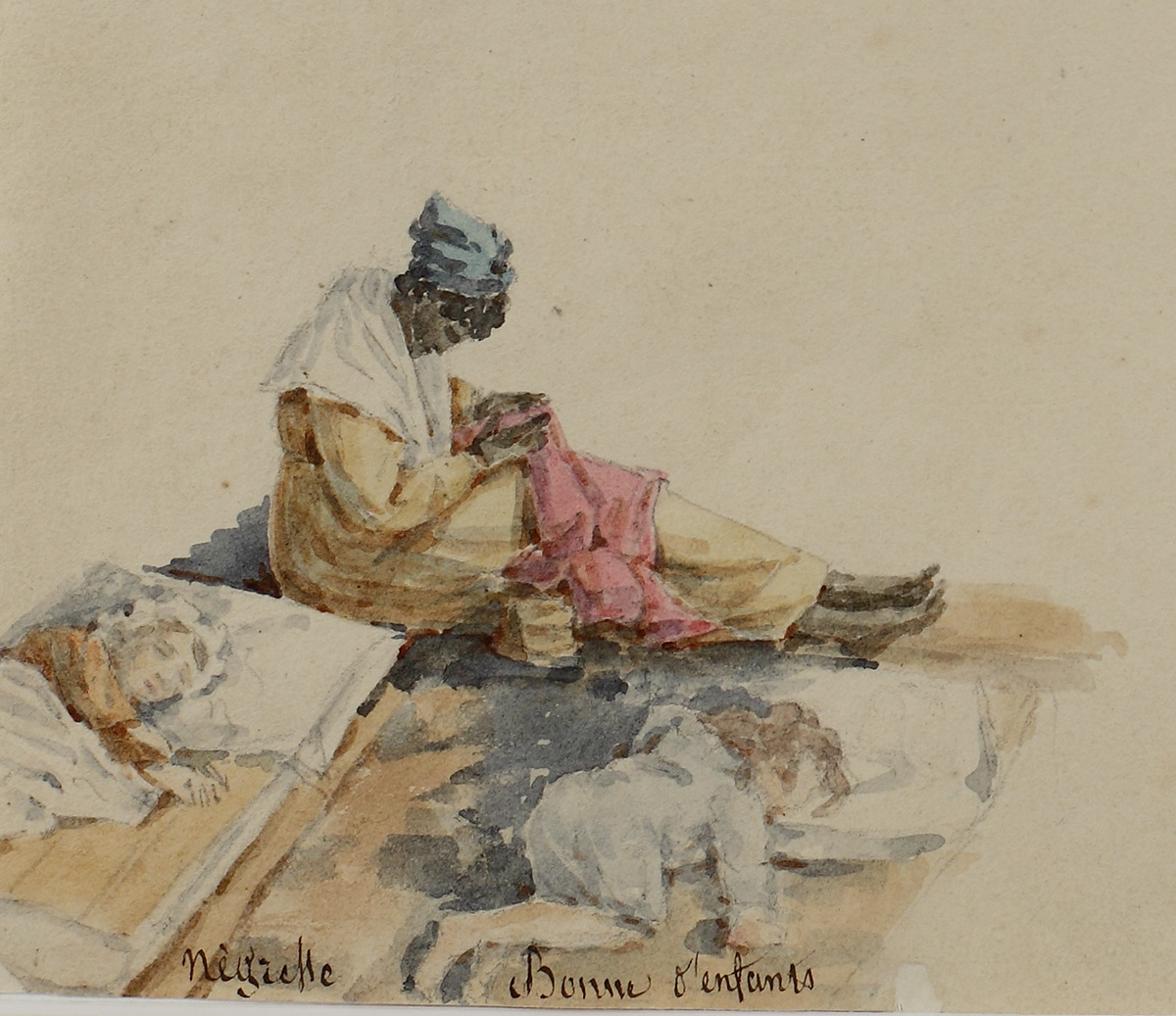

Nevertheless, the enslaved masses were not a uniform, homogenous group. The ‘Noir de pioche’ (Black labourer) worked outdoors in the field. Others were domestic workers, cooks, stable-lads etc. When staying on Bourbon island from 1827 to 1830, Jean Baptiste Louis Dumas painted scenes from everyday life. The watercolour entitled ‘Négresse bonne d’enfants’ (Negress working as nanny) shows a young woman slave sitting busily sewing, with two white children dozing nearby. Such physical proximity suggests psychological closeness between the persons concerned. Individual relations at times overshadowed the legal status of persons reduced to slavery, as defined by the Code Noir (Black Code).

Certain wills, inventories drawn up following the death of a master, family councils, even legal documents, are rife with information illustrating relations of trust between masters and enslaved persons. Understanding such relations, a priori surprising, looking into their foundations and their scope, is an interesting process. However, such investigations can only focus on the vision of the dominant group. We have no traces of the viewpoint of the oppressed, their profile appearing only as a shadow.

Lebouq was an influential person in the town of Saint-Denis. In 1792, he gave an account of two of his slaves, Pierre Jean and Modeste. He openly mentions the trust he had in them.

“Recognising in Pierre Jean many qualities and in particular his gentle character, he placed all his confidence in him, giving him authority over all his slaves.” “He was convinced that his foreman was extremely committed to his interests and that he also had a great cultural intelligence, working with diligence and caring for his slaves in a gentle manner.”

As for Modeste, “the gentle nature of this Negress and many other qualities have given rise to the affection of person present, who entrusted her with responsibility for his house and the care of his children.” Their skills and their qualities led Lebouq to delegate authority over his house to the former and the care of his family, even his children, to the latter. Modeste did not only look after the house but also had close relations with the family.

Grinne, a young pupil often wrote to his uncle. In one of his letters (1802-1803), he declared: “My dear uncle, I am delighted to tell you that my nanny has successfully given birth and given you a big baby girl.” “Send my warm regards to fat nanny and tell them I love them with all my heart.” “Send my warm regards to nanny and tell them I am still fond of them.”

Auguste Billiard, in his book Voyage aux colonies orientales (1822), again mentions this close relationship. “The nurse is given her share of the best food on the master’s table. The Negresses who have raised the children, their nannies, if I may use the term applied on the island, also objects of special attention, are no longer aware that they are slaves; they are simply members of the household.”

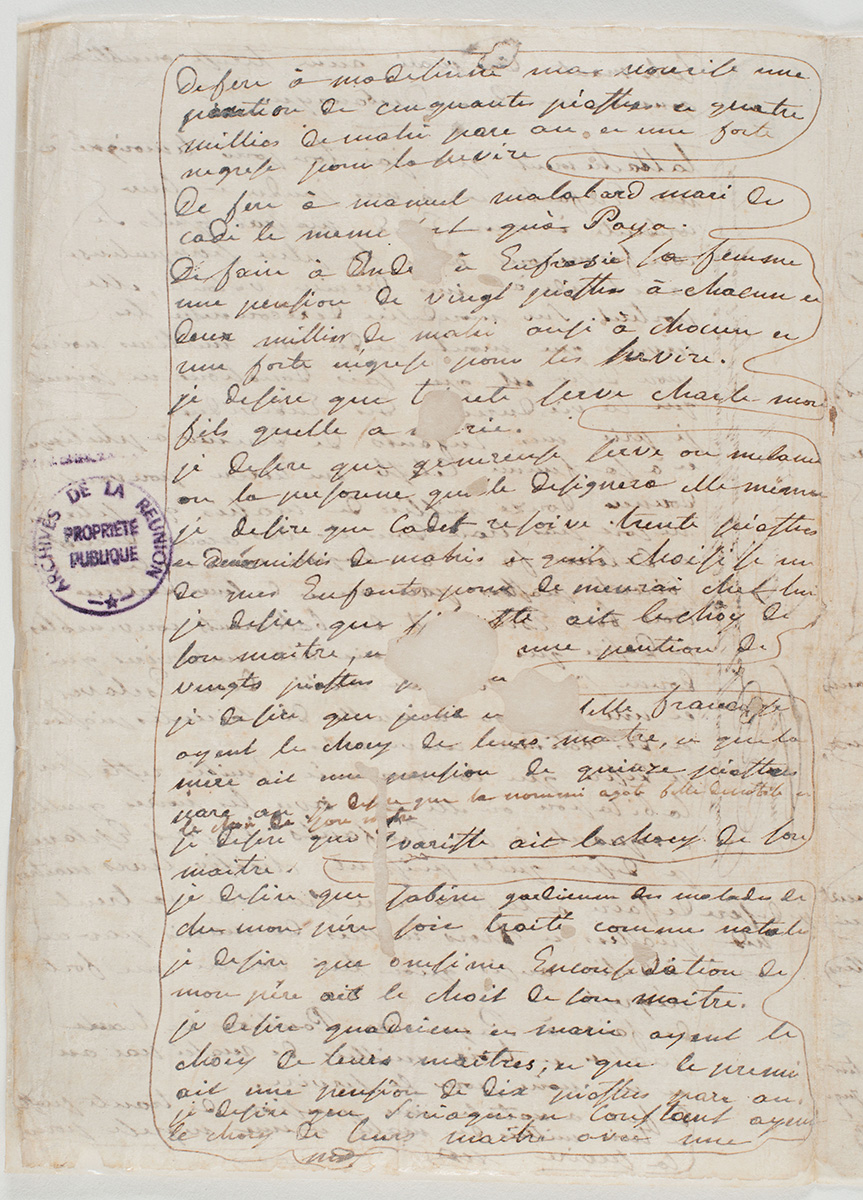

Marie Anne Thérèse Ombline Gonneau de Montbrun’s (1755-1846) mother died in childbirth. As an only child, she was brought up by a nanny named Madelaine. At the age of 52, in her first will, she left her a pension of 50 piasters et 4 bushels of corn per year, as well as a strong Negress to look after her.

Henriette Macé, in the provisions of her last will and testament, declared in 1815: “Wishing to recognise the great care I have received since my childhood from Marguerite, my nanny and slave, I declare that I do not wish her to be sold after my death, or to be dispatched with my other slaves.”

In year VI (of the French revolutionary calendar), the parents of the three minor children of the deceased Joseph Larcher took a similar decision.

Three slaves were part of his estate. The one named Zaïre, a woman from Madagascar, took care of the children. Since the death of the citizen Larcher, she had acted as their mother. Her good behaviour and her attachment to the young children, who were still in need of her care, led to her being be retained to look after the two girls. Due to his close relationship with the Pierre, a Creole slave, the citizen Larcher had specifically requested that after his death, the slave should not be sold, Actually, his services were essential for Alexandre, one of the young children, whose health was very fragile and necessitated specific care. The parents and friends all agreed that the slave named Zaïre remained absolutely essential for serving and taking care of the minors in question. It was in their interest not to sell them, the more so as this was what the father had wished, and had often declared this to them. The slaves were retained to take care of the minors, whose young age and poor health necessitated specific care.

An example was Joseph de Sabadin, a lieutenant-colonel in the infantry, who in 1792 rewarded some of his slaves who had faithfully cared for him day and night for five or six years during his sickness. He gave them and their families, a total of 13 persons, their freedom. Their emancipation would be given to them after the death of his wife, who depended on their continuing services.

In year XI, Dachery Salicant declared that in consideration of the services given to him by a certain Gabriel, a 57-year-old Creole, ever since he had been taken on, notably during the various periods of sickness the master had gone through, and also for having saved his life in a dangerous situation, he had decided to emancipate him of his condition of slavery. He gave him half a plot of land, which he already occupied.

In 1827, Augustin François Motais de Narbonne, bequeathed the said François, his Madagascan butler, to his nephew Charles Motais. When he had sent the latter to France, François had taken great care of him during the voyage.

In 1835, Clermont Hoarau declared:

“I give her freedom to the woman named Célérine, a Creole aged about 40, our servant who has always taken good care of us and tended to me during several periods of serious sickness I went through. She is also to be given means of subsistence and the 10-yearold Creole boy named Hyppolite is also to contribute to her means of subsistence. I give his freedom to the one named Hilaire, a 30-year-old Creole dwarf who served me well and took care of me all the time I was sick and who took good care of his former mistress. I give her freedom to the Creole woman Caroline, aged about 25, who has always taken good care of us and looked after her mistress, staying by her side day and night during her attacks of asthma which were unfortunately frequent. She is also to be given a means of subsistence.”

In 1846, Sieur Chrysante Bosse wrote:

“I give to my slave Marie, a 46-year-old Creole Negress, her freedom and a plot of land, as a reward for her good services and care during my old age, that, thanks to her, was prolonged

In 1821, the heirs of the widow of Pierre Mussard were all in agreement. In her estate, their mother left two women slaves, Negresses named Euphrosine and Rozalie, both Creole. Though being of great value to them due to the services they had rendered both to their parents and to them personally, these two slaves could not be valued, separated or sold.

In 1840, Mrs Marie Geneviève Goureau, widow of Amalvain Euger wrote, “As my slave called Sélérine, a Creole, has always behaved loyally to me, my poor husband and all my children, after my death, I beseech of my children not to list her in the testament or to sell her, to give her her freedom, allowing her to do as she will and live where she wishes. This is my reward, given for the affectionate and respectful care this good Negress has always shown us all.”

In 1837, Mr Dubuisson, a land-owner in Saint-Gilles, drew up his will in the following terms: “I give and bequeath to Miss Sidonie Frétigny, a Creole whom I emancipated and who became my trustworthy woman servant, all I own on this Bourbon island: furniture, mobile goods and real estate I own at the time of my death, as fair reward for her work, integrity and care given to me.”

In 1818, Guillaume Antoine Desjardins was particularly mindful of the welfare of three of his slaves. He had brought Pèdre, over 70 years of age, and Pétronille, over 65, to Bourbon island from India. They remained faithful to him, serving him diligently over a long period. He granted them the possibility to choose where they would continue working after his death, as well as a small amount of money to enable them to obtain “some sweetness” and “some comfort” in their old age. Similarly, Léocadie, a Creole Negress slave aged about 50, had been born on his estate, and brought up by the deceased mother of Desjardins. He granted her freedom for the good services she had given him constantly during his childhood, that she gave him every day through her kindness, her regular presence and her attachment to his person in his old age.

Louise Ticot, married name Malbeste, had an Indian Malabar slave named Bélizaire. He had been working in her service for about 20 years, was reliable and loyal. In 1810, she declared he should be emancipated within five years after her death, during which time he would work in the jeweller’s shop with her eldest son, to whom she specifically recommended Bélizaire.

In a number of wills, it is clearly declared that the faithful slaves will live under the master’s roof.

Henriette Macé asked Advisse, her eldest son, to take the slave named Marguerite to live in his house, to feed her, house her and take care of her for as long as she would live, and finally to give her medical care, as she would have herself, had she been alive.

The heirs of the widow of Pierre Mussard agreed that Euphrosine and Rozalie should choose under whose roof they wished to settle, and that this person would house them, feed them and care for them and their health in the event of sickness.

Similarly, in 1822,Gardye la Chapelle declared that Paulin, who had always been a faithful and affectionate servant, would be free to remain in the family, choosing whose roof he would remain under, the person being under the obligation to take him in “but not as a slave since, in reality, he has never been such in the family; but as a good servant who has served us well, and who deserves a reward, and to grant him a small salary, sufficient for his care.”

There are other cases for which we have no tangible declarations, but for which doubt is hardly possible. Permanent care given to members of the family or taking care of babies necessarily involved the slave living under the master’s or mistress’s roof. Common sense clearly leads us to this hypothesis. A range of elements enables us to come to the obvious conclusion that the slaves lived under their masters’ roof. The master’s house was not a fortress inaccessible to the servants. How to imagine, even for practical reasons, that the trustworthy slave would have to leave the owner’s house to go and sleep or even eat in his own house, when he or she needed to change nappies, feed and ‘provide health care’?

However, we have no information concerning the practical organisation. When the house was inspected to prepare the inventory following a death, the notaries would go from room to room, naming each one, taking notes and listing personal belongings, linen, clothing, crockery and opening chests, wardrobes etc. They often mentioned the slaves’ huts, the ajoupas, without stepping inside. They would mention handkerchiefs and the blue fabric used to clothe the slaves. But this was purely factual. When the inventory of the estate of Madame Desbassayns was drawn up in 1846, in her mansion along the Chaussée Royale in Saint Paul, the officer from the ministry mentioned the bedrooms, sitting room, the veranda, study, cabinets and dining room. This was also the case for her estate in Saint-Gilles. At no point did he mention spaces or rooms set aside for a domestic slave and no mention is made of any belongings, clothes or otherwise, that might have belonged to her or him. In actual fact, no mention is made of them in any of these cases. Did the slave sleep in the same room as the baby or the sick person? Did he retire to an adjacent room? In actual fact, we may conclude that the question is of little importance, the only certainty being that cohabitation, at least occasional, remained a tangible reality, as did the shared intimacy.

This trust between persons formally separated through their legal status initially appears, as we have already seen, surprising. It remains difficult to explore its intimate consequences. Regarding the slave, we cannot measure to what extent it stemmed from flattery, the hope of a better future, becoming the envy of the others, while supposing – and herein lies all the complexity. – resignation, the hard acceptance of their condition, even a certain alienation of the person. Links were sometimes broken. Pierre Jean, a trustworthy man belonging to Lebouq, already mentioned above, ended up turning against his master. He planned to assassinate him and his whole family and was condemned to death. Many were also more sincere. Links built up over a long period, sometimes over several generations, as declared by a number of masters, bear witness to this phenomenon.