He was also the descendant of Françoise Chatelain (sometimes known as Crécy), another person well-known on the island who, before marrying Augustin Panon, had buried three husbands and had several children. All this explains the considerable number of relatives of different degrees mentioned in the diaries kept by Henri-Paulin.

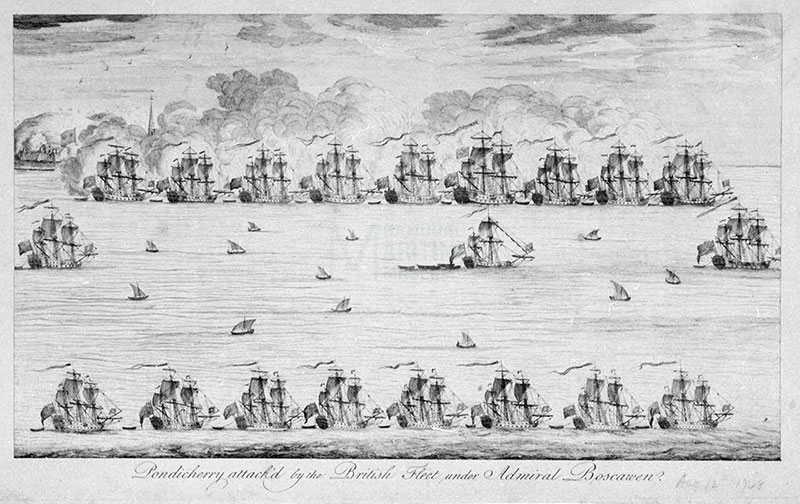

Henri-Paulin had a long and rather brilliant military career. As an ensign in the militia on Bourbon island as from 1744, in 1751 he left for India with the Volontaires de Bourbon sent in reinforcement for Dupleix. Appointed lieutenant in 1758, he took part in a number of battles, during which he was injured (in his writings, he declared that his right arm was ‘crippled’), until Pondicherry was taken by the British in 1761, following which he was imprisoned. On returning to Bourbon island in 1773, he was made major of the militia of Saint-Paul and in 1776 was appointed knight of the royal and military order of Saint Louis, a distinction that served as a kind of stepping stone towards nobility, the symbol of which, a golden cross displaying the image of Saint Louis, he would proudly wear.

Said to be ‘powerfully rich’, Hanri-Paulin was undeniably a member of the category referred to as ‘Gros blancs’ (powerful white families), even the island’s largest landowner and possessing the greatest number of slaves. In 1763, he already owned ‘260 acres and three quarters’ of land, acquired by his maternal grandmother, who had died ten years earlier. However, he really began to acquire a fortune when, on 28th May 1770, he married Marie-Anne-Thérèse-Ombline Gonnea-Montbrun, the only daughter of his cousin Julien Gonneau. He himself declared in his writings that she was the ‘island’s richest heiress’. At the time, he was 38 years old and Ombline was not yet 15! They had 13 children, nine of whom reached adulthood and who, in their turn, had many descendants.

Between the time of their wedding and the start of the French Revolution, the couple built up a huge fortune in the form of land. In 1789, the Desbassayns owned 420 hectares in estates (six plots in Saint-Gilles measuring a total of 150 hectares, two in Saline and Trois-Bassins measuring 145 hectares and 125 hectares in Bernica). In 1784 the couple owned 254 slaves, and 348 in 1790. In 1797 the figure rose to 417. When the inventory after the death of Henri-Paulin was drawn up in 1800, they listed 451. They owned four mansions, one in Trois-Bassins and another in Bois-de-Nèfles, used mainly for storage, a third in Saint-Paul and the largest in Saint-Gilles-les-Hauts, the current museum.

The crop covering the largest area on their estates was maize, the staple used to feed slaves, but also consumed by a large number of whites. However, their true wealth, that gave them their reputation, was based on the sale of coffee and cotton in Europe. With the large amounts of money earned from these crops, the Desbassayns bought a large number of objects in France, to decorate their mansions or to sell on the island at a comfortable profit. Henri-Paulin also invested in shipping activities, as well as protecting his finances by investing in various State enterprises.

Henri-Paulin was undoubtedly the inhabitant of Bourbon island about whom we have the greatest amount of information, thanks to the great many written documents he left. Having received an apparently limited education and writing in a poor and rather laborious style, with no regard for spelling rules, his documents almost give the impression of that their author wrote under force. Like his father before him, he kept a family record book, which mainly mentions the fertility of his horses and the maize harvest, while also mentioning the birth of his children, as well as those of his slaves. Above all, however, he kept a record of the two journeys he made in France, the first in 1785, the other in 1790-1792. These records are completed by lists of purchases, already made or to be made, expenses and invoices. There is, in addition, a lengthy correspondence with members of his family and various friends, notably two important sections: his correspondence with the Gérard de Lorient family, long-time friends and business partners, as well as correspondence with his cousins named Lagironde. Another very precious source of information about him is the inventory of his belongings, drawn up after his death by his notary and friend Elie Philibert Chauvet on 30th of October 1800 (post-revolutionary date expressed as ‘8 brumaire year IX’).

First of all, he was a remarkable head of family. The purpose of his first voyage to France was to visit his three eldest sons, admitted to study at the very aristocratic secondary school of Sorèze, run by the Benedictines and a royal military academy. His made his second journey to accompany two of his younger sons to France, with the aim of perfecting their education, as well two of his daughters Marie-Euphrasie and Mélanie, which was far more unusual for the period. On returning to Reunion, on 13th April 1799 Mélanie married Joseph de Villèle, future Prime Minister of France. The journals of Henri-Paulin do not only reflect the character of a man concerned with the schooling and social success of his children, but also that of a very caring and sensitive father.

An ordinary man endowed with a solid peasant common sense, Henri-Paulin would often make fun of Parisian snobbery, in particular the ‘frenzy’ of wishing to see and comment all events. In truth, however, he also experienced this same frenzy, fed by a truly exceptional vitality for a man who, for the period, was relatively advanced in age. Apparently, his objective during the relatively short periods he spent in France was to attend every possible performance, any event of historical or social interest, to see any ingenious mechanism, any theatre performance in fashion or even a simple street show. In short, he wished to be present wherever something curious was to be seen, whatever the nature of the curiosity.

His trips to France represented for him the opportunity to accomplish long-standing dreams, the first being the possibility of meeting the king and seeing the court and the residences of prestigious Frenchmen. In the provinces, he visited a whole array of Roman ruins, cathedrals and castles. However, his interest was not limited to the famous buildings. He also visited far humbler places which, in his opinion, were worth the detour, such as all kinds of workshops, market halls, hospitals, asylums, prisons and even – blocking his nose with a handkerchief – the mortuary at le Châtelet!

However, though his ‘frenzy to see everything’ was a sign of his open-mindedness, it also at times revealed a certain forced determination, even conformism. There were, for example, various performances he attended because, as he wrote, they had to be seen ‘at least once’. He also recognised that certain little plays performed at the Palais Royal were ‘not very interesting’, but he attended them systematically even so, since ‘that is where you can meet people’.

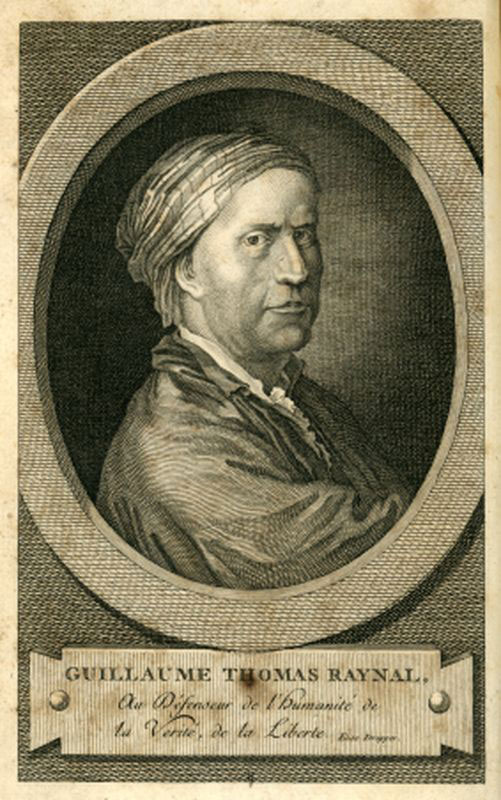

He showed a true passion for the theatre and his journeys enabled him to buy a large number of books. Classics, starting with Molière, which he particularly appreciated, 91 volumes of Voltiare, the Encyclopédie, but also the philosophical and political history of trade and of establishments set up by Europeans in the two Indias by abbey Raynal, considered at the time to be an anti-colonialist and abolitionist rebel, as well as ‘books bought under the table’. We can, in particular, note his taste for historical works, travel writings and political essays.

Through his education, certainly also by family tradition and, like the vast majority of his contemporaries, he was a Catholic. In every town he travelled through, he would systematically visit the church, whatever its importance or artistic value. Respecting God was one of the basic principles of the extremely moralising lessons he would give to his children. However, even though he often went to mass, never in journals do we have the impression of his feeling any genuine religious emotion, even any true sense of the sacred, with the exception, perhaps, of when he listened to Carmelite nuns singing in the abbey of Saint-Antoine.

He expressed a great deal of scepticism when attending certain popular devotional ceremonies and expressed no anger at the Revolution claiming that ‘the clergy must become the true shepherds of the Lord’. Consequently, he approved of the measures taken against the monastic orders which, like many of his contemporaries, he saw as being dens of laziness, greed and vice. At times his discourse was frankly anticlerical. For example, at Saint-Eustache during the funeral of Beaulieu, a relative of his, he expressed feelings against ‘all the persons assigned to this sort of ceremony who, like vultures or hawks, make a living from dead bodies …, all these fat potbellied flesh-eaters, rejoicing in the death of their fellow men.’ However, as regards religious reforms, as in all other fields, he wished for a certain degree of moderation and felt concern before the premises of de-Christianisation in 1793.

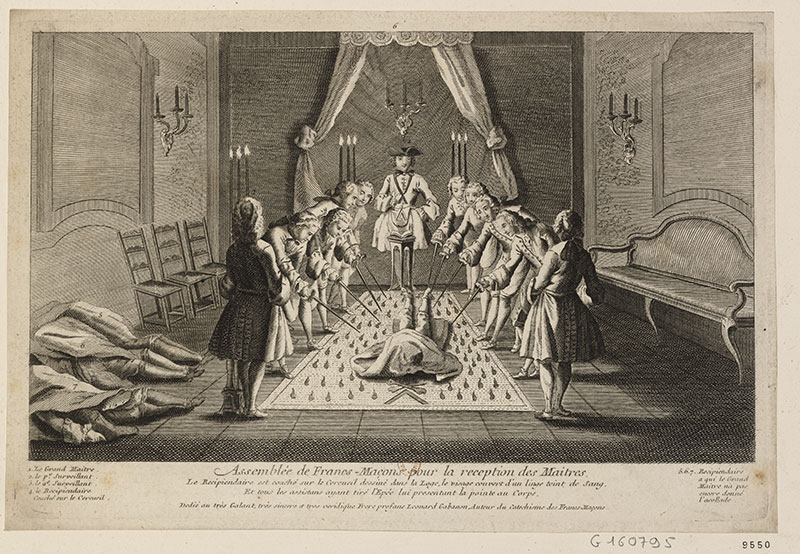

What inspired him was Freemasonry, more than Catholicism. Even before his first trip to France, he became a Freemason and many of his closest friends belonged to the same ideological movement, which, since the foundation of the Grand Orient order in 1773, had been enjoying considerable success in enlightened society. During his second voyage, at least in 1792, he regularly attended the Grand Orient headquarters in the rue du Pot-de-Fer, as well as the lodge of La Réunion des Amis Intimes, where he was made knight of the Rosicrucians on 26th July. On 26th August 1792, shortly before his departure, he was appointed ‘officer of the Grand Orient’.

Many of his closest acquaintances were also Freemasons, such as Pierre Alexandre de Beurnonville, who would become Minister of War in February 1793 and who, in 1780, was appointed venerable of the lodge ‘La Parfaire Harmonie’ in Saint-Denis and in 1778 was also made National Grand Master of all the Lodges of India. Such was the case also of Bertrand, Lemarchand and d’Etcheverry, three members of parliament or future members of parliament for Bourbon island. Freemasonry also opened doors for him, such as that of La Fayette who, at the time, was at the peak of his success.

If we read his account of his second journey to France, politics was apparently a subject which he not only found unpleasant to discuss in society, but which was also outside his field of competence. However, this was simply the expression of a passing exasperation before the notion that ‘there is (no longer) any pleasure at being in society, due to opinions which have become more and more extreme.’

In his first diary, indeed, politics plays only a minor role. He simply confirms that he is a convinced monarchist and that when he saw the French king for the first time on 12th July 1785 at Versailles, he experienced a ‘feeling of joy (impossible to) express’. However, this is hardly surprising coming from a man owing his success to the army, and nothing distinguished him from the majority of French people at the time, as is expressed in the many pages of the 1789 ‘Cahiers de doléances’ (Journal of grievances).

During his second journey, he evolved quite radically on the political level, keeping very well informed, first of all through the newspapers, which he referred to as ‘papiers-nouvelles’ (‘new-papers’), notably on questions of foreign policy, but even more by listening to what was being said in public places, in the street and in restaurants. His favourite spots for observing and obtaining information were places where people liked to stroll: the garden of the Tuileries, the Champs-Elysées and above all Palais-Royal, where he sometimes spent hours, for example during the Easter crisis in 1791, when he would listen to ‘groups proposing motions and others discussing the day’s affairs’. He liked to question fellow strollers, delighting in gossip and above all exchanging ideas with his colonial friends concerning the latest events in the Mascareignes islands, discussing with them at length about the future relationship between France and her colonies.

Deep down, he wished to remain a simple witness, retaining a neutral position. Listening to passionate discussions between persons who did not share the same political opinions, he rejected all forms of fanaticism and preached tolerance and union. However, he was not insensitive to signs of ‘the new France’. On two occasions, he was delighted to attend the National Assembly and did not miss important ceremonies of the new political regime, such as the funeral of Mirabeau or the funeral procession in honour of Voltaire, preceding their burial at the Panthéon. Above all, he shared the enthusiasm for important events, where a feeling of national unity appeared to be strengthened, such as the three celebrations of the Federation, held in 1790, 1791 7092, as well as those which marked the adoption of the first Constitution of the kingdom in September 1791. He was present when the royal family was transferred to the Temple after the attack on the Tuileries and also attended the solemn proclamation of the ‘Patrie en danger’ (Nation in danger). By chance, he also encountered the federated troops who had marched up to Paris from Marseille and who were to play an important role in the fall of the monarchy.

Fully aware of the gradual decline of the image of the monarchy, he declared himself very hostile to emigrants and very shocked by the king’s attempt to flee. While disapproving the ‘nonsense’ of the people’s declarations and acts during the transfer of the royal family to the Temple, declaring that not only ‘the whole of Paris’, but also ‘the French departments are for the destitution of the King’ and that the latter “no longer enjoys the trust of the people, nor the love of the French in general, (since) they will always reproach him with slaughtering the French, acts for which he is declared to be responsible”. In his opinion “it is not possible that Louis XVI will become king of the French once more”. However, it was the incompetent monarch that he condemned, rather than the monarchy in general.

He wished, however, to remain optimistic and even though the spectacle of internal divisions ‘often put him in a bad mood’, he trusted the passage of time and the wisdom of the elite governing France and Europe, who were, in his opinion, “a group of men who, thanks to their healthy philosophy, are capable of leading the majority (of the people).” It was a true profession of faith in Man and in internationalism, in keeping with the spirit of Freemasonry.

Witnessing the extreme tensions disturbing France at the time and fearing that his island might undergo the same fate as Saint-Domingo, ravaged by a terrible civil war after a violent insurrection of its slaves in August 1791, in mid-1792, he decided to hurry back to Bourbon island, accompanied by his children. However, at the time of the terrible September massacres, it turned out difficult and even dangerous to travel to Lorient, and it was only thanks to the help of a fellow Freemason that he succeeded in escaping from a delicate situation in Saint-Cloud.

On arriving in Lorient, he learned that his friend Jean Gérard had been massacred by the people and in order to be able to sail from France, he was forced to make a vow in favour of the new Republic, thus becoming, at least in the eyes of the law, one of Reunion island’s first Republicans, he an old monarchist soldier!

Back in Reunion in early 1793, he appears to have led a fairly discrete existence, letting his wife, who had already done so during his absence, manage his estates along with his eldest son Julien-Augustin, also called Desbassayns, who later became one of the leaders of the conservative party. Struck down by disease in October 1799, he died on the 11th October 1800 following a long period of suffering. He refused ‘the consolation of religion’, as Jean-Baptiste de Villèle deplored in a letter written to his brother Auguste. It was a surprising decision coming from a man was actually quite a conformist. A few years later, Jean-Baptiste married Henri-Paulin’s daughter Gertrude Thérèse.

Finally, we can declare that Henri-Paulin Panon Desbassayns, despite a certain degree of pettiness and his lack of cultural and artistic education, in many respects appears to have been a good representative of the spirit of Enlightenment, at least on the scale of Reunion.