These two-storey stone structures belonged to notables of the colony: Julien Gonneau-Montbrun (1727-1801) and his son-in-law Henry Paulin Panon Desbassayns (1732-1800). The architecture of the three houses differed from the other constructions situated in the rural zones of the colony.

A historical document written by Jacques Lougnon in 1989 indicates that the three houses were constructed by Henri-Paulin Panon Desbassayns: the one along the Chaussée Royale in 1776, the mansion in Saint-Gilles-les-Hauts in 1788 and finally the house in Bernica was constructed in 1789. Only Lougnon proposes this chronology, which cannot be confirmed through historical sources and there are no dates indicated on the buildings, with the exception of the house in Saint-Gilles-les-Hauts (1788). Bernard Marek , in his work on the history of Saint-Paul, also assigns the construction of the three houses to Panon-Desbassayns. In 2011, Guy Panon de Richemont contested the hypotheses proposed by Lougnon and Marek, and in his work focusing on the genealogy of the first member of the Panon family arriving in Bourbon island, noted that it was Julien Goneau-Montbrun who initiated the construction of the house in Bernica, as well as the one along the Chaussée-Royale.

Julien Gonneau-Montbrun and his son-in-law were certainly both linked to the three houses. After a successful military career in India, Henri Paulin married Ombline Gonneau-Montbrun (1755-1846) in 1770. At the time, she was 15 years of age and Julien’s only child and heir. It appears that from the start of their marriage, Julien Gonneu-Montbrun associated his son-in-law in the management of his estate. A large proportion of Gonneau-Montbrun’s income came from his property in Bernica, where he grew coffee, cotton and food crops. This ‘dwelling plot’ consisted of a yard with a house, its outbuildings and probably a slave camp. As elsewhere in the west of the island, the yard was situated at the edge of the estate, between the agricultural land and the savannah grassland. The site currently bears the name of Maison Blanche (today the high school of La Salle Maison Blanche), in the lower part of what is now the village of Guillaume. Gonneau-Montbrun also had a property called ‘Grand Cour’, in the centre of the town of Saint-Paul, a vast ‘terrain d’emplacement’, a local expression used to refer to an urban property. The entrance to the latter was along the Chaussée Royale, a street laid out in Saint-Paul as from 1769.

The most likely hypothesis regarding the person behind the construction of these houses is the following: owner of a fairly large fortune, Julien Gonneu-Montbrun financed the construction of the house in Bernica, as well as the one along the Chaussée Royale. Following a proposal made by Henri-Paulin Panon Desbassayns and under his supervision, the Saint-Gilles-les-Hauts mansion was exclusively assigned to the latter.

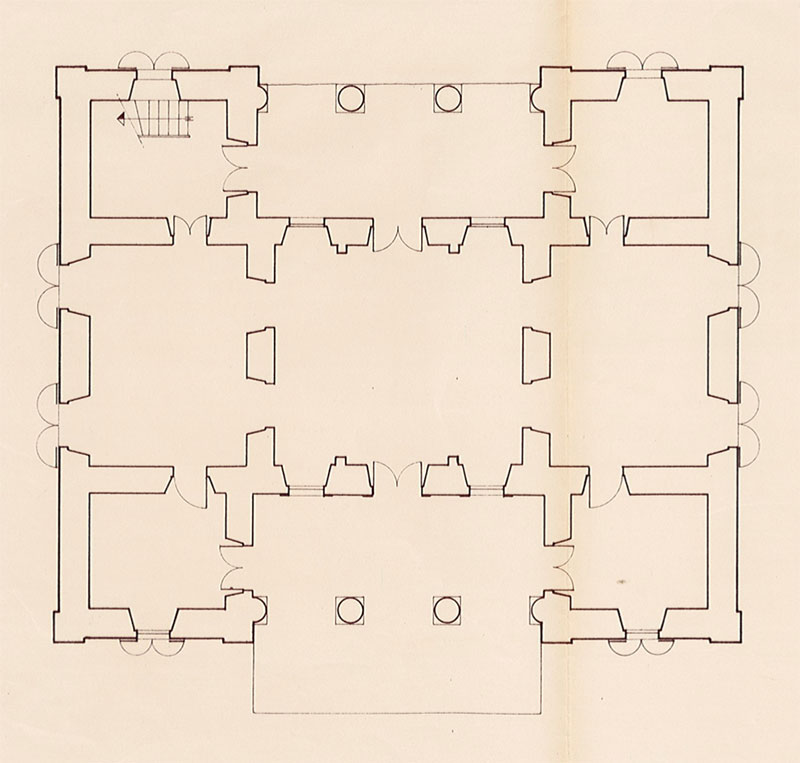

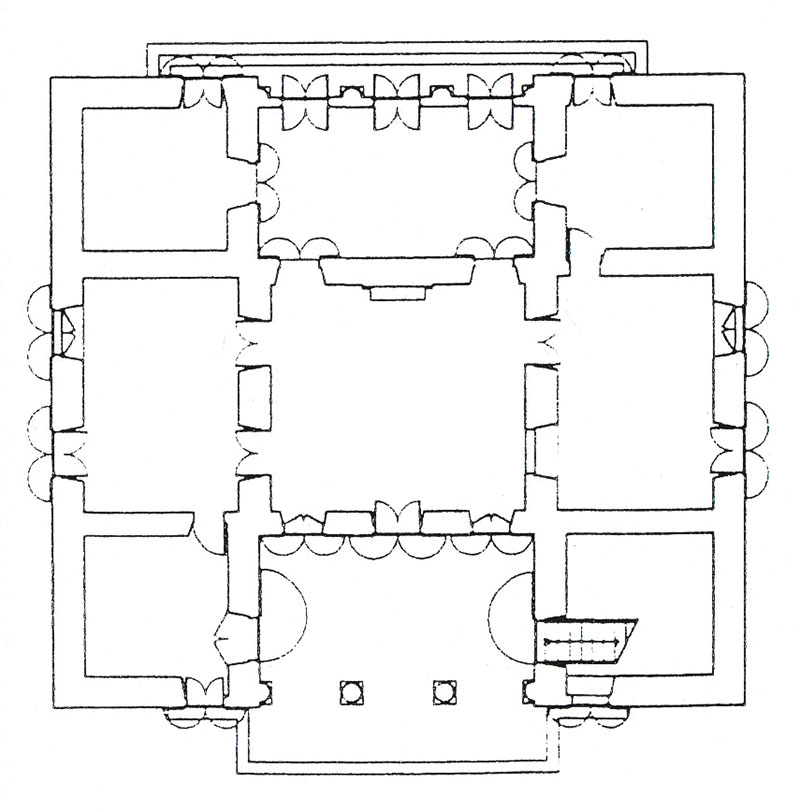

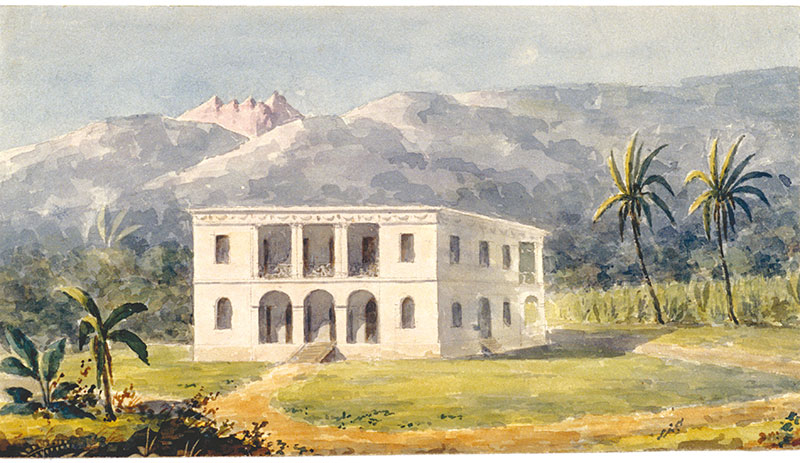

The three houses present a number of similarities: a rectangular plan, virtually identical façades, notably the presence of superimposed verandas along two sides and an interior layout, both on the ground floor and on the upper floors, set out around a large central hall.

The design was clearly influenced by Indian models, probably noticed by Panon Desbassayns when he was a soldier in the region of Pondicherry in India between 1751 and 1763. Since the 1730s, the French trading post had been enjoying a period of political and economic development, leading to thriving urban construction: Indian shopkeepers from the town, as well as Europeans, had houses built for them using brick, with tiled roofs or roof terraces. The French East India Company constructed prestigious official buildings, such as the famous hotel built by the governor Dupleix. Having to move around various battlefields due to the Franco-British conflict, Panon-Desbassayns did not permanently reside in Pondicherry, but was able to appreciate the town at the peak of its development, before its total destruction in 1761.

Indian-style opulence is reflected in the houses later constructed on Bourbon island. The heavy columns supporting the verandas along the east and west façades of the Chaussée Royale and Saint-Gilles-les-Hauts mansions present similarities with certain French constructions existing in Pondicherry in the 1750s and 1760s. The same can be said for the roof terraces, a common feature of Indian houses, constructed using the technique of a solid slab (argamasse). We cannot be certain of the contribution made by Indian masons during the construction, though it is probable that Henri-Paulin was in contact with workers from the French trading post after his return to the island. Some of these workers may have come to Bourbon island during the construction.

A more detailed observation of the three residences, related to their period of construction – the 1770s and 1780s – allows us to propose the hypothesis of a second influence as regards the style of the constructions: that of neoclassicism. This architectural style developed as from the mid 18th century in Europe and was very widely adopted, notably throughout the French and English colonies. The general layout of the houses, the symmetry of the main façades and the interior layout of the rooms reflect the neo-Palladian edifices constructed in England or France as from the 1750s and 1760s.

The Desbassayns mansions, atypical and unique on the island, reflect a stylistic combination of Indian techniques developed in Pondicherry, as well as European influence. We can here apply the term of Neoclassical Indian architecture.

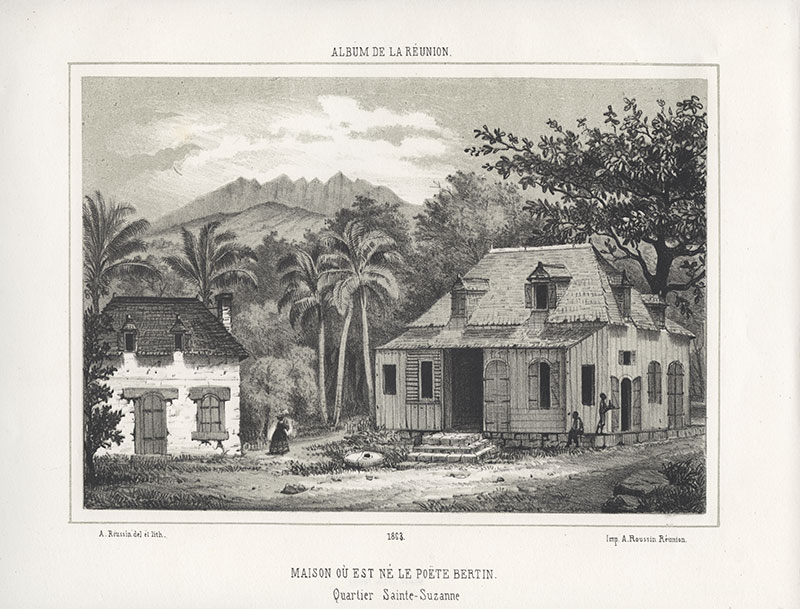

According to Albert Jauze , the average area of an 18th-century house on Bourbon island was approximately 29.5 m². These wooden houses, generally with a roof of palm leaves, had low ceilings and were dimly lit : “It is far easier to use timber, a freely available material, for which tried and tested techniques have been brought over by naval carpenters from Europe.” Very often, these houses had only one storey and a two-pitched or four-pitched roof. A lithograph by Antoine Louis Roussin and a photograph taken in 1897 showing an 18th-century house give a more precise idea of a typical spice-plantation or coffee-plantation owner’s house.

Stone was used for construction in exceptional cases as from the second half of the 18th century . However, “An individual constructor wishing to [use stone for construction] must not only be able to afford to buy lime [for the mortar], but also find competent workers. … Lime, manufactured using coral, is produced in two localities on Bourbon island [in 1770], at Repos Laleu and la Rivière d’Abord.”

These details bear witness to the exceptional and ostentatious character of the Dessbassayns mansions, constructed using plastered cut stone, with masonry basalt quoins. Due to their size, covering an area of approximately 590 m², set out on two levels, these mansions were the largest in the colony during the Ancien Régime (period of royalty in France) . Only one other private construction competed with them during this period: the Chateau du Gol, constructed around 1747 on the plain bearing the same name, in the district of Saint-Louis. The design of this mansion was the work of Antoine Marie Desforges-Boucher (1715-1790), a French East India Company engineer and governor general of the Mascareignes Islands from 1759 to 1767. It has a main building with a first floor and dormer windows and arcades on each floor along the south façade. Desforges-Boucher seemed to have been inspired by the ‘malounières’ (vast mansions) built by Breton ship-owners.

While the verandas of the Desbassayns mansions were not a totally original feature, their design, on both storeys, was exceptional for the 18th century. The only other example of this design is the north façade of the rectory in Saint-Denis, constructed in the mid 1750s, which has now undergone alterations. In addition, the existence of verandas along two of the façades of each house, in Villèle (Saint-Gilles-les-Hauts), as well as the one along Chaussée Royale, has no equivalent in other houses contemporary to the period. These create a large room which protects the central hall from the sun’s rays, and is a space for relaxing, sheltered but opening out onto the garden. The house in Bernica only had verandas along the west façade, now masked by additional elements constructed during the 1970s. In Saint-Gilles-les-Hauts, the verandas along the east façade were closed off after 1848, but those along the west façade remain open to this day.

Constructed in the late 18th century, the three Desbassayns mansions inspired no other notables in the colony during the following century, with the exception of just one: François-Xavier Bellier-Montrose. Between 1825 and 1827, probably following the plans drawn up by Jean-Baptise Reynoal de Lescouble, he had a large family mansion constructed in Bois-Rouge (Saint-André). The mansion, constructed in stone, had a double veranda along the north façade, reflecting those of Saint-Gilles-les-Hauts or of the ‘Grand Cour’. The house in Bois Rouge originally had a slab roof, like the Desbassyans constructions. However, it is not possible to declare with certainty that the latter served as a model for the Bois-Rouge construction.

Ombline Panon-Desbassayns inherited the property of Saint-Gilles-les-Hauts after the death of her husband in 1800, then, one year later, that in Bernica, as well as the plot of land along Chaussée Royale following the death of her father. After her death in 1846, her estate was shared out: Saint-Gilles-les-Hauts was inherited by the de Villèle family; Bernica became the property of Joseph Panon-Desbassayns, Euphrasie Pajot, Ursule Hamelin and Claire Vecth, all descendants of the matriarch and the ‘Grand Cour’ property remained undivided. Both estates included sugar factories constructed during the 1820s – 1830s.

From 1846 to 1974, the Saint-Gilles-les-Hauts property belonged to the descendants of Jean-Baptiste de Villèle, until it was bought by the Departmental Council of Reunion. During this period, the main modifications concerned the east façade, where the verandas were closed off in order to enlarge the house. During the 1930s, the house appears to have been renovated, since during this period, the single-casement window shutters were replaced by double-casement shutters. Since 1974, it has been a historical museum and the object of various interior modifications.

In 1847, the estate in Bernica was handed over to Edouard Manès, after which it was the property of the Etchegaray family from 1855 to 1873. The house was not modified and at the end of the 19th century still had a roof terrace and probably open verandas on its west façade. Sold to the Martin family in 1909, it may have been modified in the early 20th century through the addition of a three-section hip roof, replacing the original flat roof. It may have been around the same period that the verandas looking out over the sea were closed off. In 1920, the house became part of the property of the Eperon S.A. (corporation). Then, on 18th December 1940, the administrators of the company sold the house, along with three hectares of surrounding land, to the Christian Brothers, who wished to establish a secondary school there. The Brothers carried important modifications, notably to the façades, adding additional wings. Today, it is one of the annexes of the La Salle Maison Blanche High School.

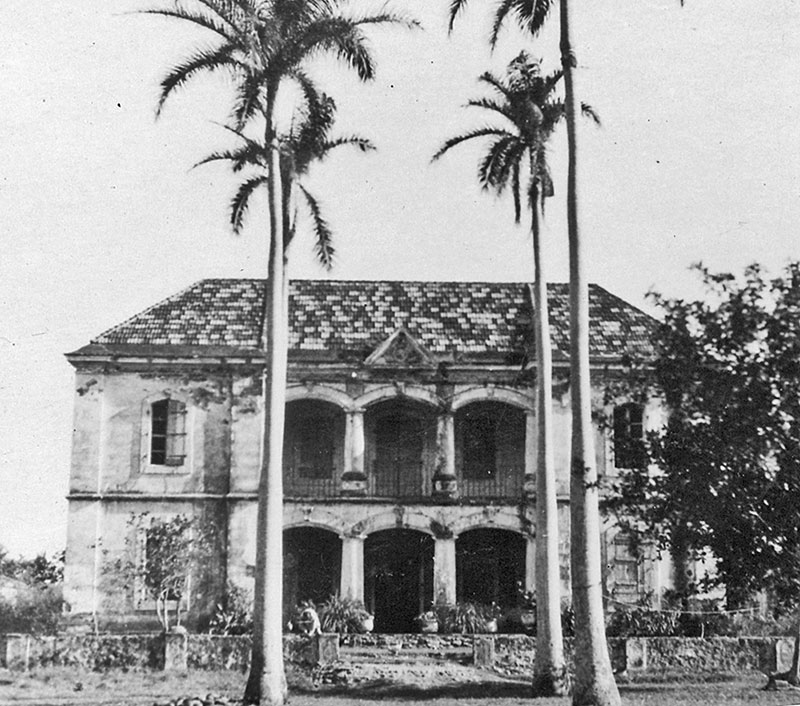

Finally, from 1846 to 1854, the property along the Chaussée Royale, was not divided up. It was auctioned off on 9th July 1854 and became the property of Camille Jurien de la Gravière, the only child of Joseph Panon-Desbassayns. Six years later, on 18th September 1858, Camille, a very pious woman, donated the plot of land to the bishopric. The latter set up a high school there, named Saint-Charles. During the second half of the 19th century, a tiled roof was raised on top of the flat roof-terrace. Around 1874, when the high school was transferred to Saint-Denis, the house remained unoccupied and started to fall into decline, finally becoming totally derelict in the 1950s. The roof had disappeared, as had the floorboards, windows and shutters. The plasterwork was also severely damaged.

Finally, an agreement was signed between the bishopric and the Chinese Kuo-Min-Tang foundation and the house was renovated in 1959. Until 1973, it was occupied by a Franco-Chinese school, under the impulse of father Antoine Lan Pin Ho. The ground floor rooms were used as classrooms and the upper floor as a dormitory. When the school was closed in 1970, it was used as a warehouse and then once more as a cultural centre as from 1982, with the installation of the Franco-Chinese cultural association, which had its head office there until 2011. Since then, the bishopric has handed over the house to the town hall of Saint-Paul.