“The foremen are very precious to us; it their hard work; the activity in the workshops depends on their hard work, their skills and their faithfulness … as do, to a certain extent, the prosperity and the safety of the colony. We hold them in great consideration when they respond to our trust, we prefer them to white leaders.”

This was how the inhabitant – the word used to talk about planters on Bourbon / Reunion island in the early 1830s – expresses his appreciation of foremen, the ‘trustworthy’ slaves who used to lead the groups of Blacks out in the fields, those ‘transmission belts’ who acted as intermediaries between the masters and the masses of slaves. He expresses a rare vision of slaves and of slavery. The masters set up a hierarchy among the slaves. They would asses the capacity of each slave, recognising his or her ability to learn, to develop, which, traditionally, was denied to them.

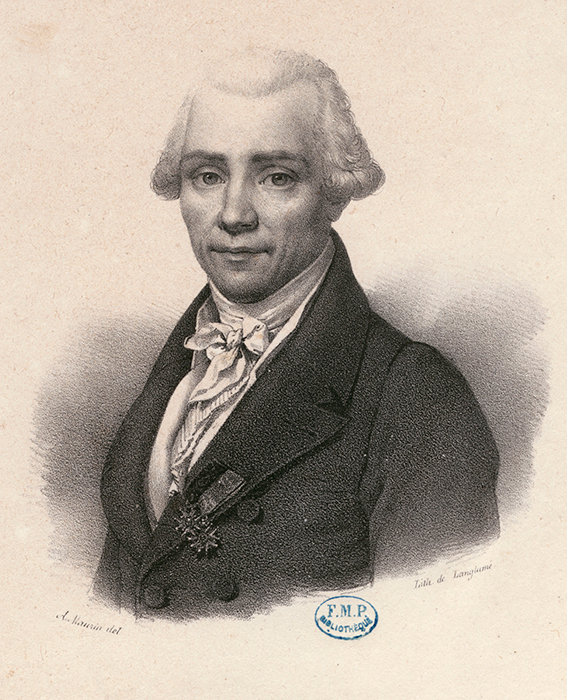

The inhabitant in question was Charles Desbassayns (1782-1863), the fifth son of Henri-Paulin and Ombline Panon-Desbassayns, referred to as “Vilmur” by his family. His words indicate that for the planters, slavery was going through a period of transition. To a certain extent, Charles Desbassayns was the man representing the transition on Bourbon island. He was one of the main actors of the development of the sugar industry on the island as from the 1810s, an agro-industrial upheaval which led to a change in the slavery society. He attempted – in vain – to alter the island’s political status. He accompanied the abolition of slavery, a transition imposed by the Second Republic (1848). He also wished to appropriate the Catholic religion to the island’s industrial economy.

Today, history has abandoned the idea of individuals’ lives being predetermined by supra-individual forces, Hegel’s ‘Universal spirit’, the ‘masses’ defined by the populists and the ‘forces of production’ of common Marxism. History now questions these ideas. Certain individuals create history, through the general character of their specific activity. Being the products of history, they also determine history. Charles Desbassayns was one of these individuals.

How did Charles Desbassayns become who he was?

The first signs go back to his early years. He was only seven when he travelled to mainland France with his father Henri Paulin, with a second journey in 1789, together with his brother Joseph and two sisters. A few years later, his father sent the three eldest brothers to study at Sorèze. Joseph and Charles did not follow their example. After granting each of his children a capital of 3,000 F in private income, the father added to this sum investments in public funds. During this period, Charles followed the teachings of the early school curriculum, while his father, during visits to friends, took an interest in mills, fire pumps and mechanics in general. In September 1792, during the period of massacres, he decided to sail back to Bourbon island, in the company of a tutor. Charles was only 10 years old at the time.

The Desbassayns parents, to make sure their children would continue to be comfortably off, would send a considerable amount of colonial goods to the United States, since Bourbon island frequently traded with the US during the embargo. Charles Desbassayns’ father then acquired land and property in New York, as well as in the states of Massachusetts and Maine. To keep an eye on his finances in America, he sent his second son Henri, referred to as Montbrun there, and entrusted him with his two young brothers Joseph et Charles, to give them experience in trading in a context of security, liberty and order. The three brothers never saw their father again, who died in 1800. Impressed by the entrepreneurial efficiency of the Americans, Charles learnt a lot from his stay in America. His ideas broadened out, his Creole patriotism was reinforced through his contact with American civic pride and his desire for general improvements and progress dates back to this period. In 1803, Charles sailed back to France, where he studied Chemistry under the supervision of Louis Nicolas Vauquelin (1763-1829), professor of chemistry at the Collège de France and the Muséum d’histoire naturelle (Natural History Museum). Through his contact with this eminent chemist, a man having a thorough knowledge of reasoned preparation of chemical products, Charles developed an interest in chemistry that he later applied to sugar, as well as acquiring a basic knowledge of science that, thanks to constant reading, enabled him to master the intricacies of the sugar industry.

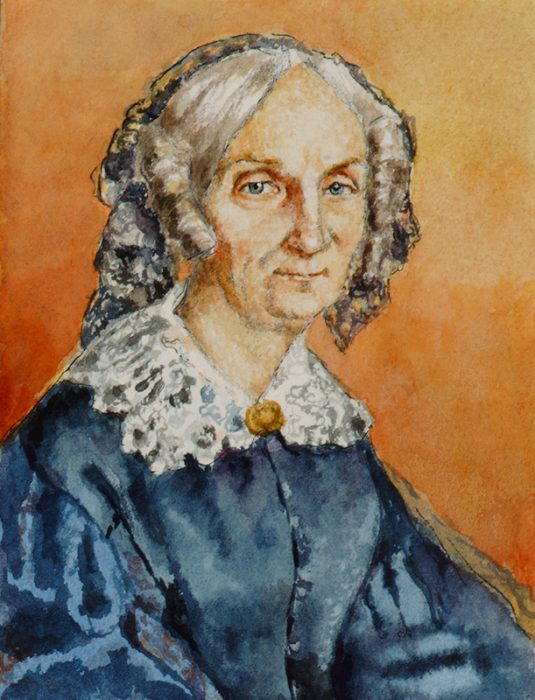

Charles and his brother returned to Bourbon island towards the end of 1806, both deciding to follow in their father’s footsteps and work in agriculture and later acquiring a brilliant reputation in this particular field. Charles retained the example of his paternal and maternal models, which had led him to develop through constant imitation. From his father he acquired the spirit of moderation, order and planning. Obsessed by success for his children, he generally married them off to nobles sometimes in search of a refuge. Charles married Sophie de Labauve d’Arifat on the Ile de France. She was the daughter of Marc de Labauve d’Arifat, a negotiator, formerly a military man, from Castres. Some charming poetry was written at the time of the couple’s return to Bourbon. As for the mother, she was of precocious intelligence, but her education had been somewhat neglected, if we are to believe her biographer and nephew. However, Charles inherited from her an ardent, enthusiastic and deeply religious mind.

As from 1810, Bourbon clearly enjoyed a favourable period for sugar production. Having lost the island of Saint-Domingo, France saw a decrease of 86,000 tons in its sugar production (81 % of the sugar exports from the islands to mainland France). The other French Caribbean islands, weakened by the British occupation and with their archaic structures, produced very little. When the Île de France was handed over to the British, the only possibilities for sugar production resided in Bourbon. Within a few months, a handful of inhabitants in the North East: Savariau, Montrose Bellier, Dioré, Fréon, Brun etc., set up sugar production. Joseph and Charles Desbassayns were at the forefront.

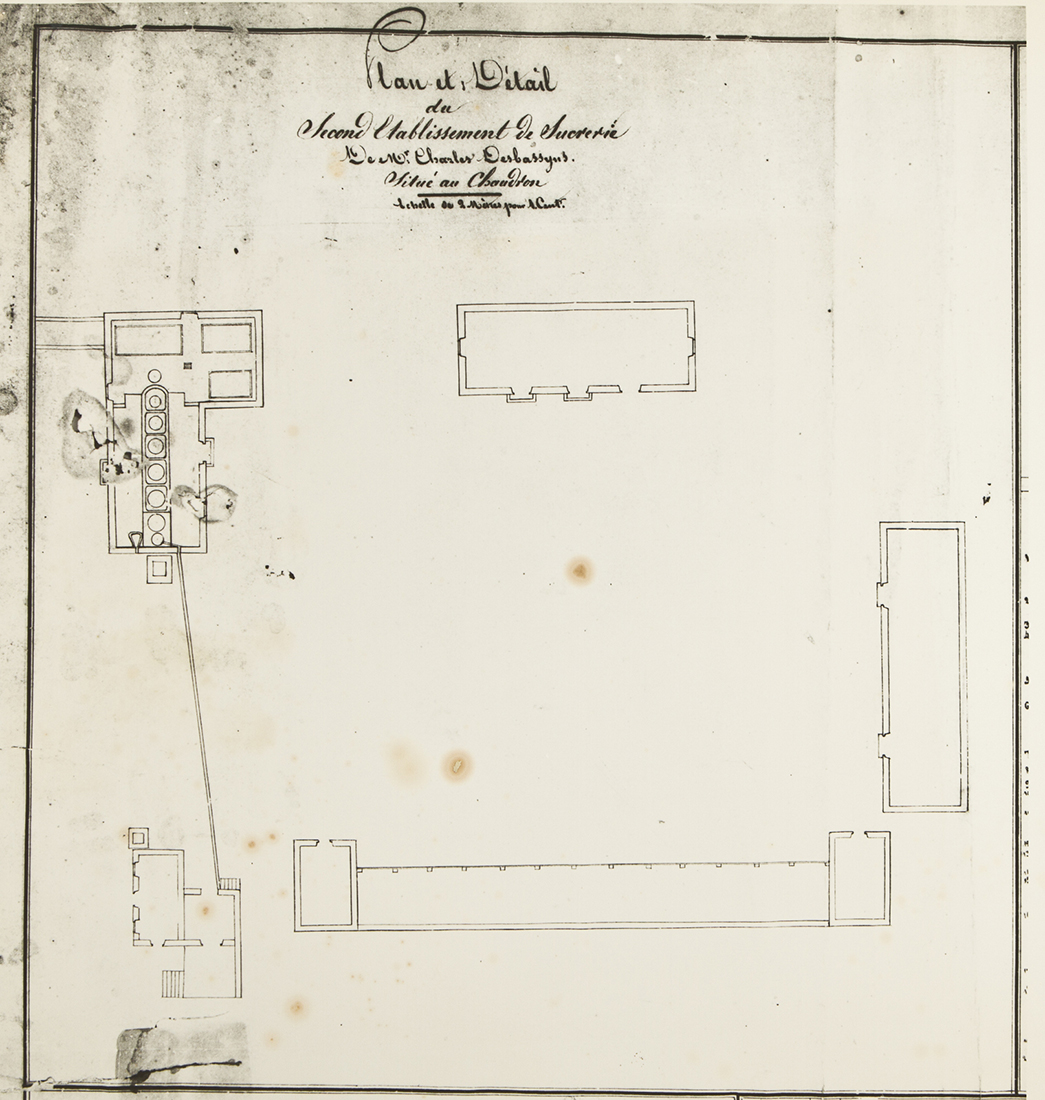

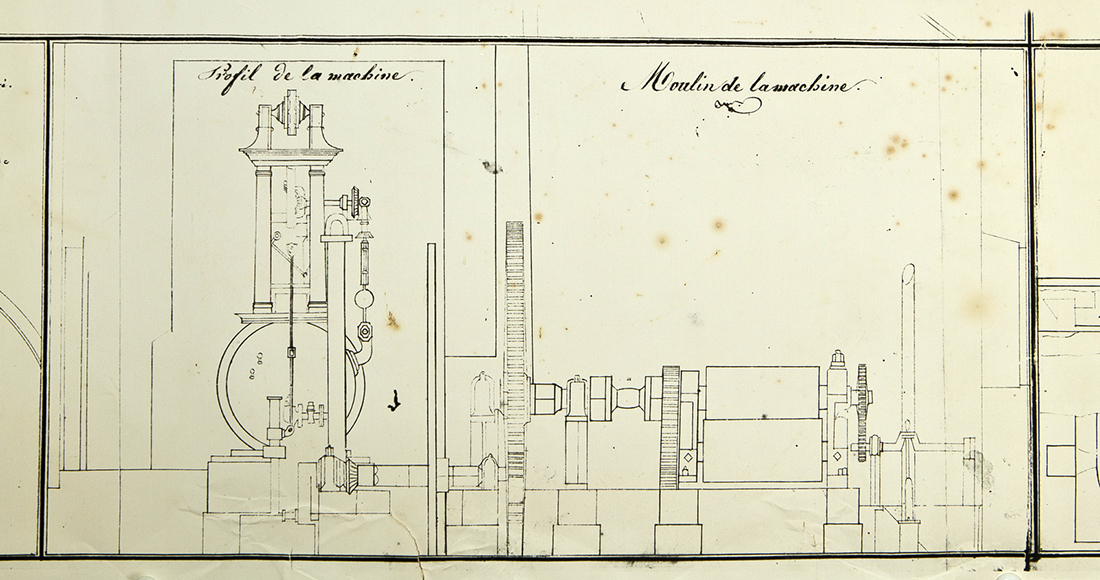

To tell the truth, the sugar plantations were initially aimed at production of arack (sugar-cane alcohol), which brought in a comfortable income. However, high taxes imposed by the government and administrative issues discouraged the distillers and profits fell. Charles, who established a distillery (‘guildiverie’) at la Rivière des Pluies, realised that sugar-cane could be used for better purposes. In 1809, he purchased an estate at le Chaudron from Guy Léon and planted it with sugar-cane as from 1813. In 1815, he set up a refinery. He continued living on the estate until 1822, when he sold it to Fréon.

As from then, Charles Desbassayns could be considered as the founder of the sugar production industry on Bourbon. The advantage that he had over his competitors was his knowledge of chemistry, his ability to consider the future of a speculative activity and his capacity to analyse problems and deal with them in a scientific manner.

He was above all lucky enough to be able to implement a new activity that was not technically constrained by decades of routine going back to the 18th century (father Labat) and that Desbassayns considered to be totally outdated, as it was in the French Caribbean. He had information brought to him concerning the sugar refineries on Île-de-France and, while doing so, came into contact with a former mechanic from Saint-Domingo. Charles decided to apply the technology the latter demonstrated to him, the most advanced of the period.

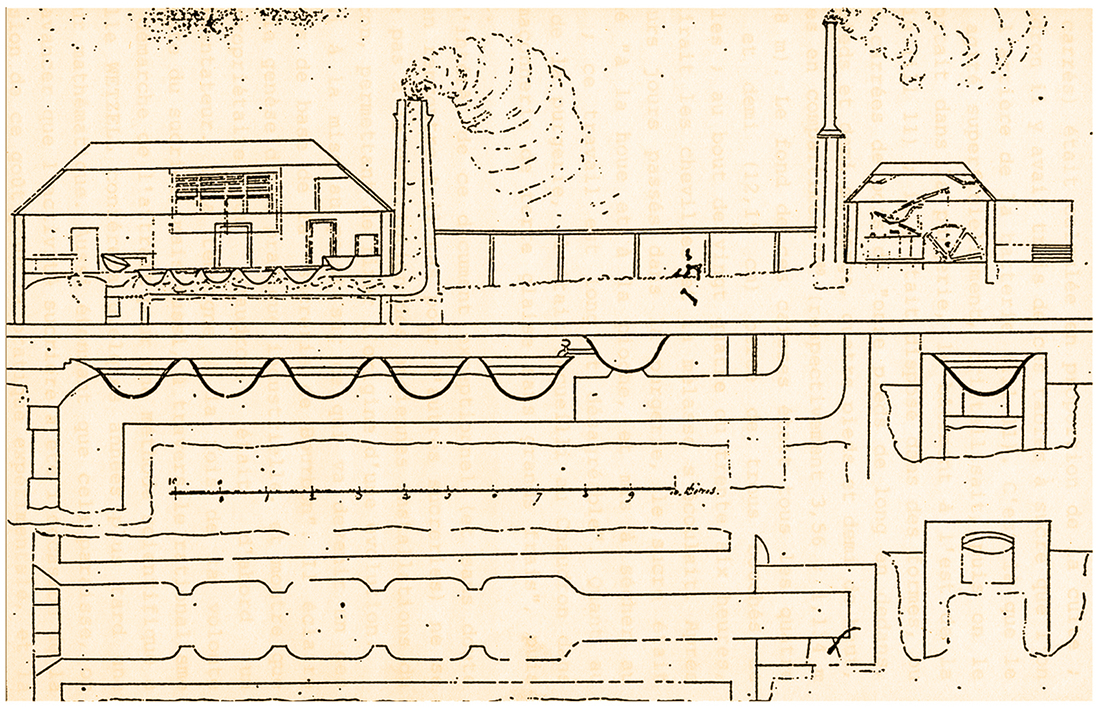

The installations he set up on the estate of Le Chaudron, which were carefully considered, combined essential innovations: a battery of five boilers set at the far end of the sugar refinery; a chimney, the height of which was calculated to provide the best possible draft; a horizontal mill made of iron, manufactured in England, powered by an English 6CV steam engine (Fawcett), replacing the cumbersome rotating mule-driven mill. The viscous syrup coming out of the final boiler was poured onto three sugar-tables to be crystallised.

Charles Desbassayns made his installations widely available for the inhabitants, inviting them to imitate his equipment. “His mill and his battery were a model; the factories which had sprung up in the past few years were nearly all constructed following his advice,” noted Billiard in the early 1820s. So, Desbassayns interconnected the technical installations in the Indian Ocean, the Caribbean and Europe and began to develop a coherent and dynamic technical space on Bourbon island.

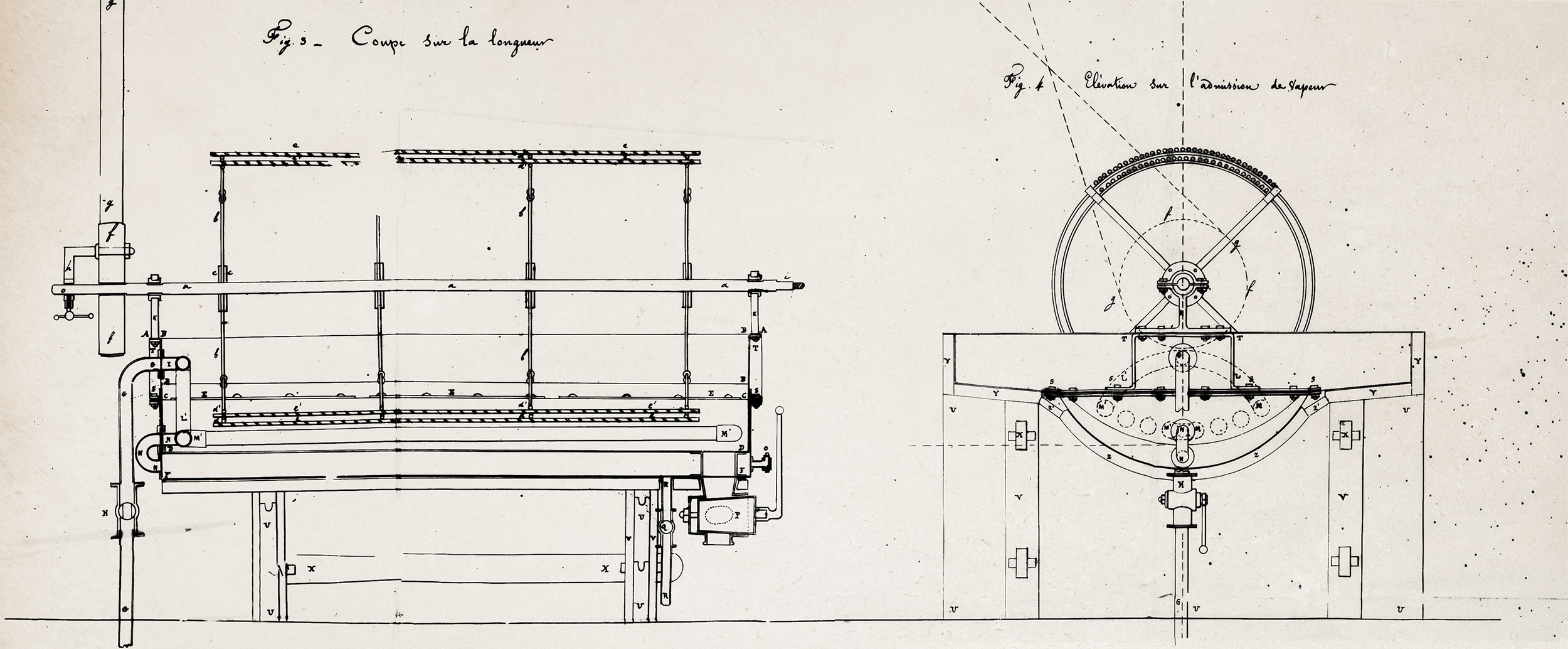

After that, he continued seeking improvement and progress for the island’s sugar industry. We can give as examples of this his recruiting his son-in-law Chateauvieux (1831), who had worked with the count of de Villiers in a refinery (1820) before running the refinery of Choisy belonging to the Périer brothers (1825). He also recruited Wetzell, who had studied at the prestigious Polytechnic institute, whose task was to improve both the quantity and the quality of the sugar produced on the island, at the lowest possible cost. Wetzell appled scientific measurements to the amount of lime added to the vesou (cane juice), on the basis of the results of fifteen years of observations by the inhabitants. From 1835, Desbassayns set Wetzell to work in his mother’s sugar refinery in Saint-Gilles-les-Hauts, where he developed local machines enabling the sugar to be boiled without it being caramelised (rotators). Thus Charles, “always in the know concerning scientific studies and

discoveries”, was an indefatigable amateur researcher on industrial improvements .

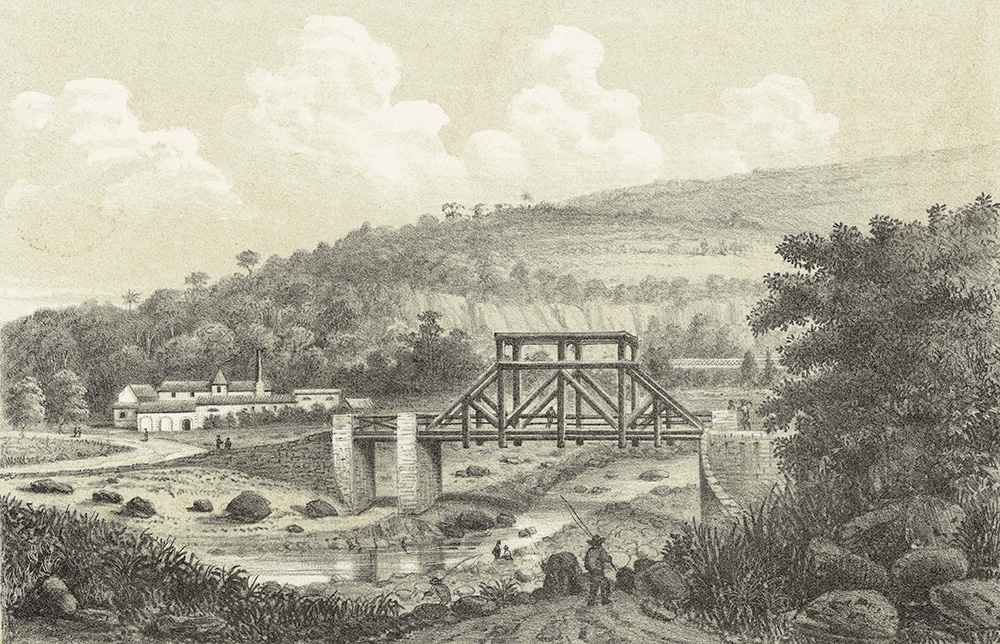

He was also interested in different strains of sugar-cane and in 1841, he received cuttings of different strains from the botanist Diard (Teboë Mara, Teboë Glaga, etc.), comparing their yields and determining the superiority of the former (Diard sugar-cane). The Mauritian botanist Louis Bouton mentioned a study Charles undertook in 1848 of the sugar-cane grown in Reunion, a work that has been lost. In the early 1850s, as president of the Chamber of agriculture, he directed observations of the meteorology in all the districts on the island, leading him to consider water supply (canal of la Rivière des Pluies) and of dedicated tracks, which inspired Lancastel, with agricultural tracks on his property, laying down stones on the Route Royale and construction of a bridge to link up his sugar refinery in la Rivière des Pluies to the capital.

“The estate belonging to Mr Charles Desbassayns and that of his mother, that came under his responsibility, were the laboratories where all systems were studied and experimented, all the ideas having the production of sugar as their

object.”

He may have felt bitter at the end of his life, for not having succeeded in rooting the prosperity of his island in solid ground: at the time of his death in 1863, the Chilo, a disease attaching sugar-cane, was rife; the price of sugar collapsed and the first closures of refineries were taking place.

“Mr Desbassayns owns 400 slaves; he whips them personally,” wrote F. R. Schack in 1830. “What he should have said was that Mr Charles Desbassayns abolished the punishment of whipping on his estate, replacing it by prison and deprivation of days of rest; in addition, such punishments were only meted out following a decision taken by a jury of Black slaves. I’m not afraid of denial or disapproval if I declare Mr Desbassayns’ estate to be a model,” replied in the same review Moiroud, former Public Prosecutor for the royal court of Bourbon island.

We shall not enter the idle debate to determine whether there existed good, not so good and evil masters … and we shall adopt the attitude expressed by one of the characters created by the woman writer Duxel Daguères: “There can be no such thing as good masters … there can only be masters, full stop.”

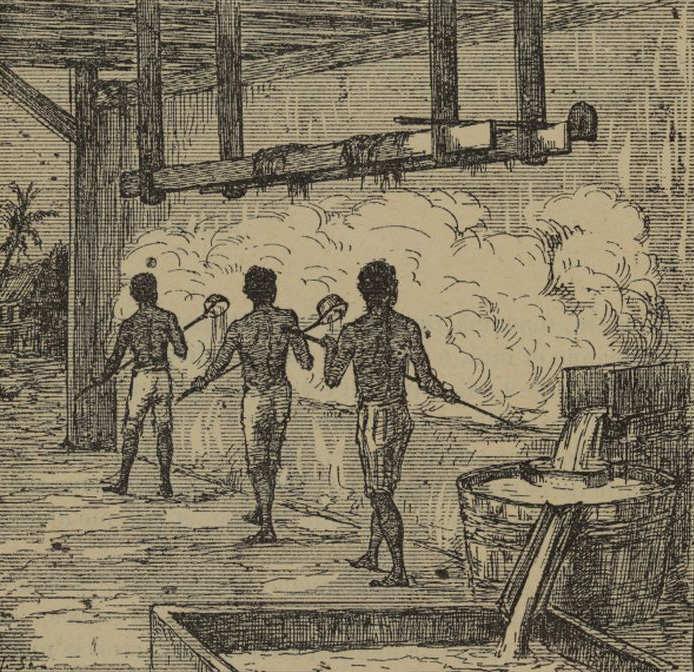

That said, Charles Desbassayns thoroughly analysed the notion of slave labour. He left us with an interesting document, entitled Notes des objets à observer comme moyen de contrôle et de surveillance (Notes on elements to be observed as a means of control and surveillance), a text which he declared to be “the most important secret of the profession.” The objective was not to improve the condition of the slaves, but to increase profits made out of the captive labour force. To this aim, he advised reinforcing and making systematic surveillance during working hours. The first way to achieve this was to increase roll-calls several times each day at the various places of labour, in order to avoid shirking. In addition, there needed to be surveillance of the slaves when accomplishing all their tasks. The headings given to the paragraphs of the regulations book speak for themselves: of “Rules of surveillance” for the hospital, “Surveying Louis Marie and Christophe” etc. However, surveillance was of no use if no accounts were given: Gentil, a smith: “Gives an account every evening and at roll-call”. Finally, there was to be surveillance between the slaves, which had three objectives: avoiding punishment, which prevented slaves from working; avoiding theft, proof that surveillance was insufficient and that the slaves were not working; making sure the work accomplished by the slaves was productive: surveillance was both dissuasive and pedagogical. On several occasions, Charles Desbassayns declared that slaves were to understand how to work and how to develop their skills. He made a note of this regarding his estate of le Chaudron in 1822: “Here, it is the slaves that run the machines and so far none of them has experienced any serious accident.”

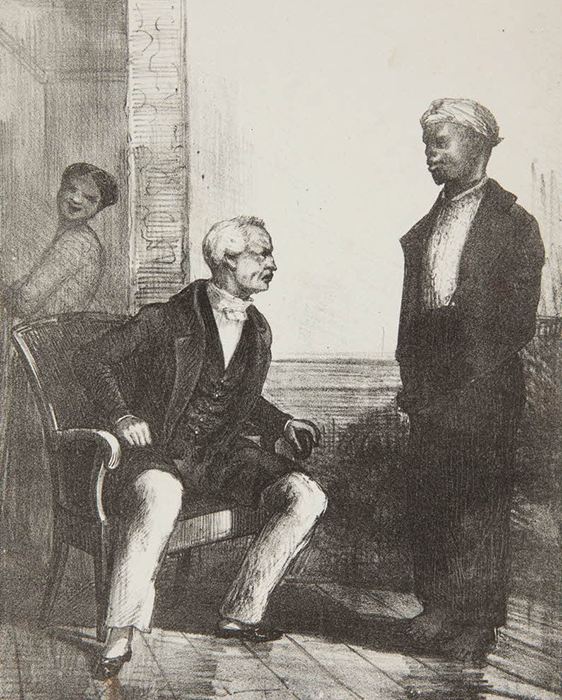

by Melle V. Monniot, vol. 2, p. 252.

Collection of Reunion departmental library

However, though making a profit out of slavery, Desbassayns accepted the idea of abolition: “The measure is inevitable,” he confided to the physician Dr Yvan, visiting Bourbon island in 1844. “However, my dearest wish is that emancipation should not be voted before the death of my old mother.” In this context, in the 1840s, with a handful of other inhabitants, he planned to convert the slaves to Christianity, which would facilitate their integration as emancipated citizens. It was on his estate in la Rivière des Pluies that in 1843, the priest Levavasseur welcomed the mission set up by Monnet. The landowner provided accommodation and food until Levavasseur managed to have a small house built next to the church. These missionaries from the order of Saint Cœur de Marie organised lavish processions. In 1844, in honour of the holy sacrament, the procession took place in the magnificent avenue leading to Charles’ mansion. Two banners and a crucifix were followed by a canopy carried between two rows of young girls, all the Blacks standing in two rows on either side.

Instead of rigidly attempting to retain his symbolic privileges, Charles Desbassayns showed a will to operate the transition between the world of slavery and the new world, nothing surprising coming from a man imbued with the ideas of Charles Fourier, and who, like the inventor of phalanstery, hated the French Revolution and hoped for “gradual emancipation”. Though we have little information concerning the dissemination of Fourier’s ideas on Bourbon island, we know that they became widespread on Mauritius island, where Desbassayns constantly had contacts, and where several intellectuals/planters, such as Laverdant, Autard (de Bragard), Leclézio, Desmarais, Bouton etc., had adopted these ideas. Unlike Fourier, these proponents of phalanstery in Mauritius openly demonstrated their piety, at a time when the Church in Mauritius was attempting to strengthen its influence, reflected by the mission of Father Laval (1841).

This explains the original attitude expressed by Desbassayns in 1848, concerning the future of the emancipated slaves. An important debate divided the Privy Council sitting on 23rd October. The sugar producer Ruyneau de Saint Georges, who was also a lawyer, declared that “emancipation being here a fact accepted in advance by a healthy majority of the inhabitants, they must take a keen interest in the future, the continuation of work and order being maintained.” He added: “As regards the salaries [of the emancipated slaves], they will necessarily today be fixed very low, since the inhabitants are all more or less lacking in resources.” In the name of “Christian” liberalism, his sense of responsibility and his adherence to the ideas of Fourier, Debassayns requested commitment to a proposal: the sugar producers would provide the land, the emancipated labourers the work force and profits would be shared. Food, clothing and accommodation would be at the charge of the emancipated labourers, in order that they may acquire habits of order and economy, which implied higher salaries, whereby he concluded: “The distinctive characteristic of the Black population is recklessness and apathy.” Ruyneau, on the other hand, declared that these costs should be covered by the inhabitants, with the salaries being appropriately reduced and a proportion set aside “to ensure the existence of the old and the sick”, which he assessed were 15,000 in number, 2,000 according to Desbassayns. It was Ruyneau’s system which was adopted. The emancipated slaves gradually became used to being assisted and the symbolic dominance of the Masters, notwithstanding emancipation, was perpetuated.

Charles Desbassayns continued to combine the social and the religious. The religious preoccupation, inherited from his mother, was reflected in the funeral eulogy pronounced over his coffin. For the abbot Fava, that being who had received so much from God, had also given back so much to God. Lagrange spoke of his active Catholic faith. Dejean de la Batie talked of the exemplary Christian, friend of the poor, the donor who had sacrificed for them part of his fortune.

He supported the Societies or conferences of Saint Vincent de Paul, before becoming chairman of their higher council. Founded in 1833 in Paris around Bailly, the Society was brought into the island in 1854 by par Albert de Villèle, his nephew. Its members carried out material and spiritual good works, with expenses in 1860 reaching 14,000 F, used to help 150 families, sending 50 children to school and making official 40 marriages between emancipated slaves.

Charles Desbassayns’ religious actions were not limited to supporting those in need. He also supported the presence of the Jesuits and when he became President of the General Council (1855), supported successive administrations in their association with the Bishop Desprez, not hesitating to provide funds for the construction of a large number of chapels, churches, a new cathedral – which was never finished – and the establishment of la Providence, which benefited from a subsidy of 80,000 F per year. Desbassayns was an example of that first generation of social Catholicism that appeared in conservative circles and was opposed to a political and economic liberalism.

This attachment he had to the Holy See was combined with a loyalty, quite late on in his life, to France and passion for Reunion: he incarnated the Creole patriotism of the period. This double loyalty was expressed later in the century by François de Mahy. However, as from the 1840s, the poet Auguste Lacaussade asserted his “double belonging” to the Creole nation and the French nation, nothing original, since it had been at the heart of the Franc-Créole ideology as from the 1830s. Charles Desbassayns’ attitude was more complex. Indeed, it seems that initially, the desire to assert his Creole identity had the upper hand. His father had already asserted it, calling himself ‘the African’ during his trips to Paris. Like his mother, Charles apparently facilitated the British occupation of 1810. Sigoyer declares this clearly in his diary: “Charles Desbassayns is one of those who gave up the colony to the British in 1810.” He did not hesitate to declare allegiance to King George. P.P.U. Thomas, in charge of the administration of Bourbon over a period of six years, added that Desbassayns was Head Secretary of the government during the early years of British occupation. Having become a legitimist in 1815, Desbassayns did, however, attempt to oppose the power of the governor, considering him to be overly intrusive concerning the affairs of the settlers. According to Thomas: “The outbreak of cholera [1820], followed by a break in communications, were pretexts that were quite easily seized upon by Desbassayns, though little exploited. They attempted to take advantage of surveillance by the government being neither sufficiently direct nor sufficiently active … took the resolution to deport the government and send him back to France… and had to seek out an arrangement so that the governor [Milius] alone would leave the colony. They considered the opportunity favourable and came to speak to me about their projects indirectly.” Thomas refused to commit this act of treason and finally the project did not see the light of day.

Following this, his attitude evolved. He understood that he could hope to achieve an important position of dignitary in the colony, whatever political regime was in power in mainland France. He was not mistaken. He was successively appointed member of the advisory committee on agriculture and trade on Bourbon in 1820, then member of the Private Council. In 1825, he was made Knight of the Legion of Honour and Colonial Councillor as from 1826. He was appointed member of the new agricultural committee in 1839 by the governor Hell. In 1848, following announcement of the revolution, Charles, the conservative sugar producer and owner of slaves, was appointed by acclamation President of the Colonial Assembly, of which the aim “must not be to create hostilities between the colony and mainland France, nor to postpone emancipation.” Elected town councillor for Sainte-Marie in 1854, he became general councillor for the same district the following year. Year after year, he was given more responsibilities: First President of the chamber of agriculture in 1854 and two years later President of the General Council. Three years before his death, he was made Officer of the Legion of Honour. So Charles Desbassayns proved that Welcome Ozoux was right when he declared “We accept all the changes of political regime that the mother country wishes to adopt, calmly and serenely, and which, once confirmed, often turn into interested enthusiasm and almost always into temporary loyalism.”

In 1863 died a man who had facilitated the transition from a colony of slavery to a colony of agro-industrial activity, Reunion island as we know it today. In a capitalist context, Desbassayns, like the other sugar producers, measured the limited profits from slavery compared to that of salaried indentured labour. He chose to maintain close links with France, on condition that these links should permanently shift from the political to the economic, following the logic of structured assimilation, which is one of the defining characteristics of the Republican regime, which then became accepted by the planters.

Charles Desbassayns had become a sort of universal authority on the island, up-to-date with the most recent studies and discoveries of science, and recognised as being an indefatigable experimenter in the fields of agriculture and industry. Any outsider coming to visit or study the colony would ask the question: “Have you seen Mr Desbassayns?”

It is related that this man, whose attachment to the island was mythical, a few days before his death, rose from his bed with great difficulty and asked to be carried to the General Council where, despite his suffering, he led important debates with lucidity.

All the dignitaries on the island, the music of la Ressource, the nuns of the order of Les filles de Marie, the Jesuits, and a considerable number of the inhabitants attended his funeral. The ceremony was led by de Lagrange, director of the interior, by des Molières, Mayor of Saint-Denis and Vice-President of the General Council, Bellier de Villentroy, President of the imperial court, Thomy Lory, Mayor of Sainte Rose and member of the General Council, Mottet, notary and member of the municipal council and Dejean de la Batie.

Today, Charles Desbassayns has been completely forgotten.