He spent the 1790s and part of the 1800s far from Mainland France but still on French soil, unlike many emigrants who left France entirely to flee the revolutionary troubles. However, his arrival in the Indian Ocean in 1791 was indeed because of the Revolution. Born in the Languedoc region of noble blood, he gave up his career as a naval officer and settled in Reunion Island.

From then on, he concentrated his efforts on maintaining the slave system, notably as a parliamentarian in the colonial assembly (1799-1803), furthering an anti-abolitionist cause to which he remained faithful until 1848 . The Mascarene Islands were the setting for his arrival into the world of politics, but also his acceptance into the Creole elite following his marriage (1799) to Barbe Ombline Mélanie Panon Desbassayns, one of Henri Paulin and Ombline’s four daughters. This alliance was consolidated four years later by the union of his younger brother, Jean-Baptiste (1780-1848), who had come to Reunion Island to escape conscription, with his sister-in-law, Gertrude Panon Desbassayns.

After Joseph de Villèle returned to his native Languedoc in 1807, he did not sever ties with Reunion Island, remaining in contact with Jean-Baptiste who had settled there permanently to look after the business activities that had been entrusted to him. And while his brothers-in-law Charles and Joseph were pioneering the island’s sugar revolution, thus requiring colonial interests to be defended in Parliament, Joseph de Villèle began to make a name for himself in post-imperial France through his hostility to the parliamentary regime and the Constitutional Charter . As mayor of Toulouse (1815-1818), then member of parliament for Haute-Garonne (1815-1830), he became the leader of the hard-line ultra-royalists, who were opposed to the revolution’s legacy. His meteoric rise brought him to the head of the government: appointed Minister of Finance (December 1821) and then President of the Council (September 1822) by Louis XVIII, his role was extended under the reign of Charles X. His influence would assist Philippe Panon Desbassayns de Richemont, another of his brothers-in-law, parliamentarian for La Meuse (1824-1827) and member of the Admiralty Council, a consultative body attached to the Ministry of the Navy and the Colonies. Facing joint opposition from the Liberals and part of his own camp, Villèle was beaten in the November 1827 elections, leading to his resignation on 4th January, 1828. Given a peerage by Charles X, he no longer held any public office after the July Revolution, but retained some influence among the legitimists. After writing Memoires (published at the beginning of the Third Republic), he died in Toulouse on 13th March, 1854.

The eldest son of Louis de Villèle (1749-1822) and Anne-Louise de Blanc de la Guizardie (1752-1829), Joseph was born into an old family of the Languedoc nobility who divided their time between the town (Toulouse) and their estate at Mourvilles−Basses (Haute-Garonne) in the Lauragais. Like many members of the French nobility at the end of the Ancien Régime, the Villèle family sought to retain their aristocratic identity.

In fact, although their lineage can be traced back to the 13th century, their ennoblement was more recent, dating back to a 1633 purchase from the office of the King’s Counsellor by Jean de Villèle. This event enabled them to recover from dérogeance (a fall from aristocratic grace) which had come about when a great-grandfather had settled as a merchant in Toulouse . This reconnection with the nobility was furthered by the descendants of the oldest son (the Caramans) and the youngest (the Campauliacs) to which Joseph de Villèle was born.

In 1777, his father bought back the land of the Mourvilles-Basses, on one hand in order to rebuild the original dominion which had been split up over previous generations, and on the other hand to acquire the seigneurial rights pertaining to it. Through this process, he became one of the largest landowners (nearly 400 hectares) in the south of Toulouse. In order to increase his income and his reputation as an enlightened farmer, his land stood out locally as an example of agricultural modernisation thanks to his use of artificial meadows .

To further elevate his family’s status and reputation, Louis de Villèle also wanted his son to join the king’s service, and sought to enrol him at Sorèze , the prestigious Royal Military School close to the family home. But, due to his lack of service and wealth, his attempt failed. Joseph de Villèle therefore saw the doors of opportunity close for him, just as he was opening up to the wealthy bourgeoisie of the provinces and the colonies, not unlike his three future brothers-in-law at the time .He chose to study at the Royal College of Toulouse, before taking the entrance examination for the Alès Naval School in March 1788 on the advice of the Marquis de Saint-Félix de Maurémont (1737-1819), a captain, friend and member of the family. Villèle admitted his lack of skills for a career as a sailor, but his success in the exam enabled him to join the modern navy that Louis XVI was looking to build. As an obedient son, he was keen to follow the wishes of his father, who was anxious to further increase the family’s status.

After a short apprenticeship period between June 1788 and July 1789, Joseph de Villèle left for Saint-Domingue on 18th July 1789 as a 2nd class navy cadet. He arrived there at the time of the first troubles and left fifteen months later, deeply marked by the widespread chaos . On his return to Brest at the end of 1790, he quickly sought a port of refuge, which he thought he would find by following Saint-Félix, who had just been appointed commander of the outpost in India. He knew the place well, having already been there twice and married a rich heiress on Isle de France . While nearly 60% of the officers of the ships choose to emigrate from French soil and three of his cousins did the same , Joseph de Villèle opted for a colonial alternative:

It is also thanks to this determination that I was able to avoid the cruel alternative of becoming an expatriate myself, like almost all the members of my unit, or of submitting to principles and follies that my heart and reason have always felt just as much…

Travelling aboard La Cybèle under the command of Admiral Saint-Félix, Villèle left Brest on 26th April 1791, reaching Isle de France after a crossing of four months. This mission was supposed to last three years, but he ended up staying much longer than expected.

From 1791 to 1793, Joseph de Villèle carried out several missions to the coasts of India on board the frigate La Cybèle. A number of reasons led to his departure from the navy on 15th December 1793: his personal convictions (the proclamation of the Republic), the insubordination of the crews (contesting orders from officers of noble origin), his loyalty to Vice-Admiral de Saint-Félix who, under pressure from popular society, had been deposed by the Colonial Assembly of Isle de France, and finally, his lack of enthusiasm for a career as a naval officer.

Shortly after arriving, Villèle joined the vice-admiral who had taken refuge in Reunion Island. This loyalty and his commitment to the very royalist Société des Amis de l’Ordre led to a brief investigation from the colony’s Jacobin authorities. While Saint-Félix was imprisoned in Isle de France, Villèle remained in limbo on Reunion Island with Dupérier and Martin, two merchants from the south of Toulouse. He hoped to go back as soon as peace returned, but this did not happen and he had no news from his parents that could reassure him about his future. After Saint-Félix was released, the young man returned to Isle de France (1795-1796), where he became estate supervisor for the vice-admiral, who planned to have him marry his daughter . But the young man had other plans that brought him back to Reunion Island.

Villèle decided to settle in the colony. After proving himself capable of learning the ropes as a new inhabitant, this status became definitive when he became owner of half a plantation located in Bras-Panon, and manager of the second half on behalf of his ‘compatriot’, the trader Martin who granted him a loan with very generous interest rates . In reality, what initially brought him here was a possible marriage with a lady from the Selhausen family , a union which was already well advanced, as the following request proves:

Last year, I obtained from you leave to come to the island of Reunion, and I have found the means to acquire a house there in the long term. I have got married there and I ask to be allowed to stay there. I hope, citizens […] that you will not want to push a young and honest man into transgression or ruin due to over-rigorous and perhaps an incorrect application of your regulations .

However, this union was perceived by his relatives as a misalliance, and never took place, to the great relief of Saint-Félix who was convinced that his protégé was one of the many ‘victims’ of J.J. Rousseau:

I have often told you that Rousseau would spoil and end up causing the misfortune of many of his disciples. I fear that the course you have probably taken according to his principles will prove one day to be real torment for you.

This sentimental break-up was painful for Villèle who waited more than two years before starting any new marital plans, ones which would conclude successfully.

He became a member of the white Creole elite in several stages:

– the family alliance through marriage to Mélanie Panon Desbassayns on 13th April 1799, consolidated by the union of Jean-Baptiste de Villèle with Gertrude on 24th October 1803;

– the political alliance thanks to his entry on 21st September 1799 to the colonial assembly on which his brothers-in-law Julien Panon Desbassayns and Jean-Baptiste Pajot already sat;

– the economic and financial alliance: Mélanie brought a house in La Saline using an advance on her inheritance and, thanks to the loan of sums she received as an inheritance following the death of Henri Paulin (11 October 1800), this enabled her husband to help his parents with his sisters’ dowry. For his part, Villèle’s contribution was to return to Isle de France to promote a trading house set up in Mainland France by her brothers-in-law Henri and Philippe just before the Treaty of Amiens was signed on 25th March, 1802.

In short, these years led to the emergence of a trans-oceanic family network bringing together two families: one Creole, the other from Mainland France, both seeking to climb the social ladder.

While institutions from the revolutionary period had been suppressed by General Decaen, Joseph de Villèle held no public office, devoting himself solely to his one goal, to return to Mainland France.

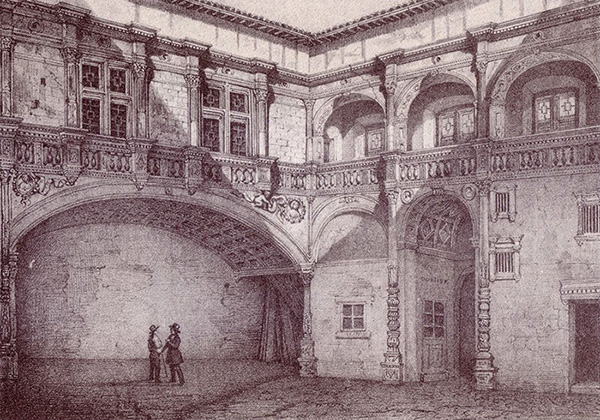

As soon as he got married, he had promised his parents that he would come back to them as soon as peace returned and take over the family estate. When the Treaty of Amiens was signed, he wanted to sell his home in La Saline to his mother-in-law, but the return of war put this project on hold. From October 1803, he therefore waited for more favourable conditions concerning his house in Olivier (Saint-Paul), busying himself with landscaping work of which he was proud: “[…] the house is magnificent. Madame D[esbassayns] is amazed by it whenever we talk a walk.”

Marked by the English blockade, this period also brought personal bereavement with the death of his daughter, Pauline Henriette . The interminable wait came to an end on 14th March 1807 when, having understood that peace would not come soon, he decided to return in spite of everything and embarked with his wife and two children for France via the United States. This return journey ended five months later. On 31st August 1807, Joseph de Villèle was reunited with his family in Toulouse, nineteen years after leaving them.

You no doubt remember that I always said that I would only marry a man with a charming face, well my dear, I have come back to your opinion, and I realise that a charming face does not bring happiness – the proof is that my husband does not have a pretty face, and that I am quite happy about it.

By marrying Mélanie, one of the four daughters of Henri Paulin and Ombline Panon Desbassayns, eight years after his arrival in the Mascarene Islands, Joseph de Villèle forged a lasting family alliance. He then fulfilled the dream of every European who came to the islands: to marry a rich Creole heiress. Melanie’s dream was obviously not to marry such a small man, with a face marked by smallpox and a somewhat nasal voice, but in Joseph de Villèle she finally found a ‘good match’ who ticked all the boxes for a higher social position.

The weight and influence of the Panon Desbassayns family in Reunionese society was nothing new. It came first and foremost from an old family group, descendants of the pioneering couple formed at the end of the 17th century by Augustin Panon and Françoise Châtelain . Mélanie was a third generation member of this Creole family, born in Reunion Island. From the first generation, the choice of spouses was based on certain criteria: nobility, military service and European origin. In 1729, Marie Panon, one of the daughters of the founding couple, married a nobleman , a choice which was imitated by almost a third of the daughters of Mélanie’s generation . Mélanie followed another family strategy by marrying a former naval officer: in the family, slightly more than half of the marriages were to army (76%) or navy (24%) officers. Finally, Joseph de Villèle was ‘European’, a privileged origin in almost half of the cases . This choice was therefore part of a social order of slave-owners based on the principle of racial inequality. As being white conferred privilege, marrying a man who was certain to not be of mixed race helped to promote or maintain a woman’s social pre-eminence.

Access to the best education is another element that distinguishes the descendants of Augustin Panon. His son Augustin studied at the Jesuit College in Pondicherry , while his grandson Henri Paulin Panon Desbassayns chose the Royal School of Sorèze for his three eldest sons, home-schooled his daughters Melanie and Marie Euphrasie while in Paris (1778-1863), sent Joseph (1780-1850) and Charles (1782-1863) to the United States, and even brought a teacher out to Reunion Island to educate his last two daughters . In spite of their father’s efforts, it must be noted that the education offered to the Villèle brothers (especially Jean-Baptiste), appears somewhat inferior compared to their brothers-in-law. However, their other assets compensated for this relative weakness, not forgetting their advantageous geographical proximity, given that they came from a region that the elders of Sorèze knew very well.

In any case, their education and general knowledge certainly helped them in carrying out their public duties. In fact, from Augustin Panon (member of the Provincial Council) down to his great grandson Julien Augustin Panon Desbassayns (parliamentarian for the Colonial Assembly of Reunion Island from 1795-1803), family members would generally take up long-term administrative and/or political roles at an early age, allowing the Desbassayns to develop into a powerful family of the elite. This explains how Joseph de Villèle’s reputation inspired confidence among the rest of this royalist family. Rumours about the ‘Saint-Félix affair’ spread across France, attracting the sympathy of Montbrun and Richemont . And by speaking in the Colonial Assembly during a heated debate , the young man showed promising skills for debate and political action. Finally, it was from this moment that a deep and lasting friendship was established with Julien Panon Desbassayns, a friendship which led to his meeting with Mélanie. and after that to be introduced to his future in-laws:

After his triumph (…) speaking at the Colonial Assembly, in the same room where, 3 or 4 years earlier, he had appeared as a political prisoner and threatened with death, he enjoyed a great reputation. (…) He was introduced and presented to all the main families of Saint-Denis. Your uncle Desbassayns was pleased to introduce him to his family. Monsieur and Madame Desbassayns welcomed him with their usual kindness, further accentuated by his friendship with their son. On his first visit to Saint-Gilles, my brother was struck by his ease of manner, combined with such honourable simplicity. He often told me that this house alone reminded him of his father’s home. Nothing he had seen since he had left it had made him feel such emotions. Of course, we did not need to convince him to come back and visit. Finally, encouraged by a few friends and without being stopped by the reserve of your uncle Desbassayns, counting even on the close friendship that already existed between them, he took steps to obtain the hand of your aunt who was only 17 years old at the time, and he did not have to wait long for his request to be accepted .

Joseph de Villèle may indeed have been a good match, but this was essentially due to his experience in commanding and managing an estate. His family’s privileged social and economic position was thanks to their role as landowners, given that they owned the colony’s largest property (420 hectares) and had the most slaves (417 in 1797).

In the end, given Villèle’s background, education, political reputation and eagerness to build a profitable estate, he was a fine match indeed, as highlighted by his brother:

[…] what they considered above all was education, good manners and understanding of agricultural work, and my brother had proved himself in all these respects. Without fear, they entrusted him with the happiness and fortune of their daughter, correctly thinking that neither of them would be compromised.

Joseph de Villèle managed four coffee plantations (see table below). He first settled on the windward coast, buying a small house in Ravine des Figues to be closer to Saint-Denis and his duties at the colonial assembly. After the death of his father-in-law, he was forced to swap with his brother-in-law Jean-Baptiste Pajot. From then on, he lived with his wife on the west coast, close to his mother-in-law.

| Date | Location | Method of acquisition | Area | Slaves | Prices |

| 06/11/1796 | Bras-Panon | Purchase | ? | 32 | 750 bales of coffee |

| 12/04/1799 | La Saline | Advance on inheritance | 30 ha | 21 | / |

| After 12/04/1799 | Ravine des Figues (Ste-Marie) | Purchase | ? | ? | 800 bales of coffee |

| 31/10/1800 | La Saline | Exchange | 30 ha | / | / |

| 04/12/1800 | L’Olivier (St-Gilles-les-Hauts) | Purchase | 30 ha | / | 275 bales of coffee |

Joseph de Villèle’s estates

The exact number of slaves owned by Joseph de Villèle is not known, but can be estimated at around sixty. One year before his return to France, he still owned 35 of them , the others having been sold to his mother-in-law at the same time as his house at La Saline. Among them, there were three family units, placed at the top of the servile hierarchy, namely the estate’s foremen Ricar and Parfait and the domestic workers managed by Manuel, the head butler .

For his slaves, Joseph de Villèle was an ever-present and demanding master, as he considered that in order to make money, watching over and managing his estate was a full-time occupation:

So far, I have been almost always very busy, and this may be something that you will find worth explaining. For I have no doubt that back in France, we are all taken for lazy and nonchalant people who spend three-quarters of their lives in a peaceful and contemplative idleness. At least this is the opinion that I have observed in the past when people describe us colonists. They are infinitely mistaken, as while they would use the term ‘owner-farmers’, we prefer to call ourselves ‘inhabitants’. Every inhabitant has a piece of land and blacks that are used to provide for themselves and their family, either to ensure a comfortable life or to make a fortune.

For him, his father-in-law was therefore the very model of an ideal estate owner:

Monsieur Desbassayns is a respectable man on this island and the one who has been working hardest to ensure that his large family may prosper, and also the one who has best exploited the land here, something only possible when it is managed with activity, intelligence and economy .

But while he was trying to fight the prejudices towards colonists, he himself would use stereotypes to describe slaves when talking to his family back in Mainland France:

Given that these slaves are totally indifferent to the success of the work and of the business, they go about it only with inadequacy and ineptitude, to the extent that if they are left to their own devices, almost no work gets done at

all .

When he left Reunion Island, his last slaves were entrusted to his brother Jean-Baptiste who bought the house at L’Olivier . All except the nanny, Nin Cadi (Manuel’s wife) who, on Mélanie’s insistence, was taken to Languedoc where she died from exhaustion just two years after her arrival .

Although he defends himself in his Mémoires , the experience and political knowledge that Joseph de Villèle forged in Reunion Island undoubtedly gave him “a taste for public affairs and the desire to get involved in them once again” . His father even saw in him the promises of a destiny on a national level: “It was in this colony that he began to display his fine spirit and true zeal for the public good. At a very young age, he told us what he would one day become […]” .

Villèle’s elevation to public office can be explained by a number of factors: personal loyalties, political convictions (royalism defined as patriotism, intense anti-republican sentiments associated with a strong position against abolition), fear of threats, both external (such as the application of the decree of 16 Pluviôse, or the invasion of the English) and from within (the Jacobin opposition, fears of a slave revolt). On top of this was his willingness to secure his own personal situation (protecting his assets, ensuring his return to France, and providing the financial assistance required by his extended family). In short, he feared everything that could have threatened the established colonial slave-owning order, going into politics in order to preserve such an order (see table below) via a colonial counter-revolution.

| Dates | Actions |

| 28/02/1793 | Signed a petition from the Society of Friends of the Order, a royalist paramilitary organisation opposed, among other things, to the change of name of Bourbon Island. |

| 21/05/1794-

03/07/1794 |

Imprisoned in St-Denis after assisting Vice-Admiral de Saint-Félix, wanted by the Jacobin authorities of Reunion Island. |

| 18th-21st June 1796 | Took part in the expulsion of Baco and Burnel in Port-Louis, who had come to enforce the abolition decree of 16 pluviôse Year II (4th February 1794). |

| October 1798 | 1st public intervention: called for the cancellation of the election of two parliamentarians of the Colonial Assembly of Reunion Island, suspected of orchestrating a slave uprising |

| 21st September 1799 | Joined the Colonial Assembly as parliamentarian for Saint-Louis |

| January-March 1800 | Opposed the independence project launched by members of the royalist faction |

| 20th July 1800 | Became a member of the Administrative Committee, the colony’s real government |

| 28th February 1801 | Became one of the 12 full members of the Intermediate Commission: the “masters of the island” |

| April-May 1801 | During the crisis in Saint-André, he participated in exceptional measures (censorship, arrests, deportations) taken against royalists who were in favour of independence and thus opposed to the colonial assembly. |

| October 1802 | Learned about the decree of 30 Floréal Year X (20th May 1802) on the re-establishment of slavery and the slave trade |

| 09/10/1803 | The end of all public functions following General Decaen’s dissolution of all institutions dating back to the revolutionary period |

The key stages of Joseph de Villèle’s political work in the Mascarene Islands

After a serious crisis resulting from the debate on independence, Reunion Island remained French and officially republican. It remained loyalist, but ran by an administrative committee which was both crypto-monarchist and anti-abolitionist. After a renewed political crisis, an Intermediate Commission took real control of the colony until Decaen’s regime was introduced in 1803. During these two years, Joseph de Villèle was a member of a veritable family-run oligarchy, since almost all the committee members were either relatives or close friends, a reactionary oligarchy which finally triumphed with the law of 30 Floréal Year X (20th May 1802), finally re-establishing slavery.

Joseph de Villèle, a forgotten politician, disparaged by Chateaubriand in his Mémoires d’outre-tombe and criticised by historians , today remains associated with reactionary policies (the ‘milliard aux emigrés’ decree, laws governing sacrilege, birthright and press censorship…), and the satirists of the time were quick to remind him of his slave-owning past:

Old man Desbassins took his gnarled cane

And delivered it into my strong hands,

And thus, to charm my lonely boredom,

I tried it out on my Blacks, learning the ropes for my future role as minister.

This article is based on our Master’s thesis (M. Doriath, Ultra-centrales colonies: les Mascareignes dans le parcours de Joseph de Villèle (1791-1807), under the supervision of C. Prudhomme, Université Lumière-Lyon 2, 2011) and our current thesis work: Joseph de Villèle et l’île Bourbon (1794-1830), research dir. F.-J. Ruggiu, Centre Roland Mounier, UMR 8596, Paris IV-Sorbonne. One of the objectives is to examine Villèle’s career from the colonial and imperial angle, as the only biography devoted to him does not focus on these aspects.

Studies devoted to the families of Villèle and Panon Desbassayns

ANTONETTI, G., ‘Villèle’, in Les ministres des Finances de la Révolution française au Second Empire. Dictionary of biographies. 1814-1848, t. 2, Paris, Chef, 2007, pp. 175-253.

DÉMIER, F., ‘Joseph de Villèle (1773-1854). Un provincial face à la France postrévolutionnaire’, Cahiers de la Nouvelle Société des Études sur la Restauration, No. XIII, 2015.

DORIATH, M., Ultra-centrales colonies : les Mascareignes dans le parcours de Joseph de Villèle (1791-1807), Master II thesis, under the supervision of C. Prudhomme, Université Lumière-Lyon 2, 2011.

FOURCASSIÉ, J., Villèle, Paris, Fayard, 1954.

MARION P., ‘Note biographique de Armand Philippe Germain de Saint-Félix (Vice-Admiral) : 1737-1819’, Sociétés savantes et Belles Lettres du Tarn, n° 31, 1972.

MIRANVILLE, A., Madame Desbassayns : Le mythe, la légende et l’histoire, St-Gilles-les-Hauts, Villèle Historical Museum, 2012.

PERRET Henri, ‘Une communauté de l’Océan Indien à Paris au XVIIIe siècle, le monde d’Henry Paulin Panon Desbassayns : tentative d’expression d’un réseau’, by Pierre-Yves Beaurepaire and Dominique Taurisson (eds.), in Ego-documents à l’heure de l’électronique. Nouvelles approches des espaces et réseaux relationnels, Montpellier, University of Montpellier III, 2003.

RICHEMONT Guy de, De Bourbon à l’Europe. Les Maisons Panon, Panon La Mare, Panon du Portail, Panon Desbassayns [etc.] et toutes leurs descendances, Paris, 2001.

WANQUET, C., Henri Paulin Panon Desbassayns, Autopsie d’un “gros Blanc” réunionnais de la fin du XVIIIe siècle, St-Gilles-les-Hauts, Villèle Historical Museum, 2011.