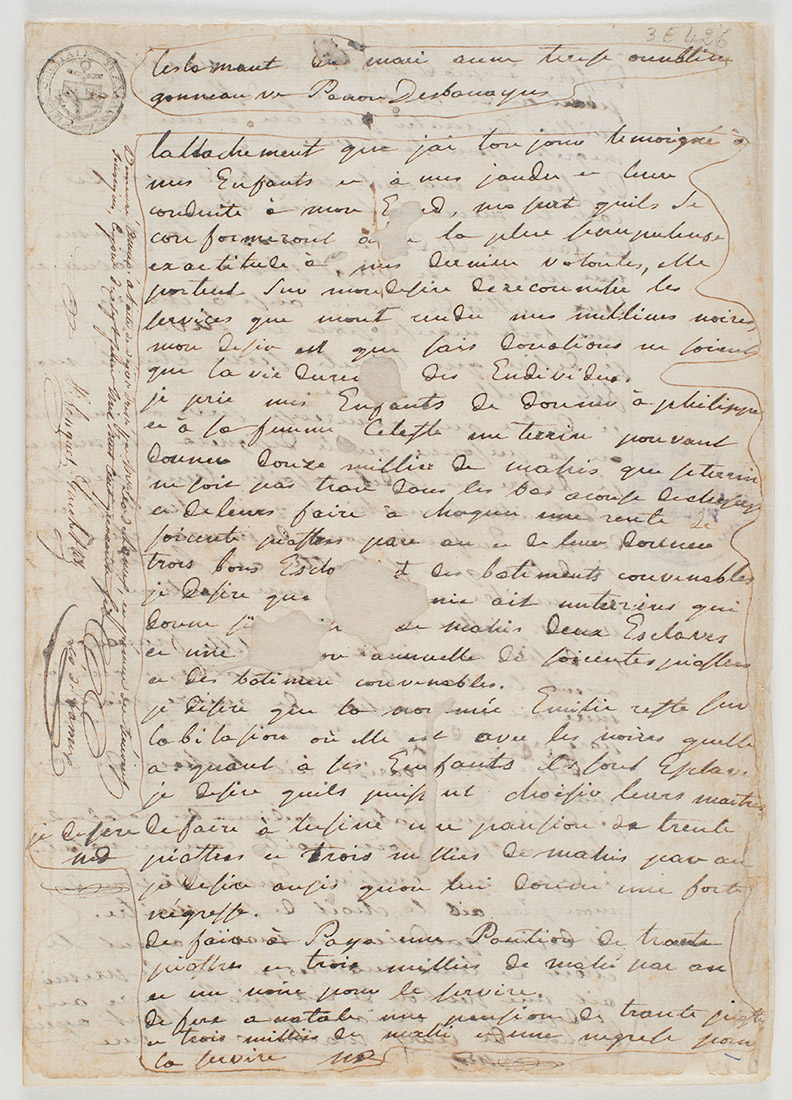

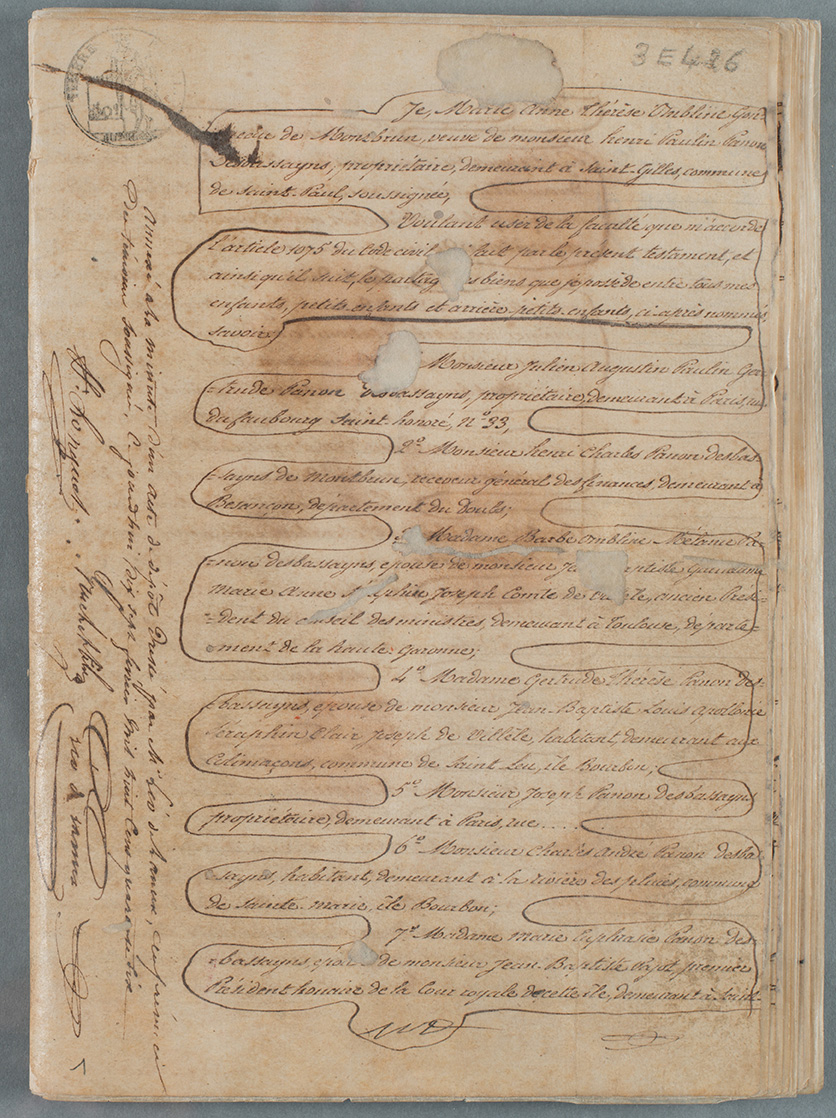

They differ in their volume (2 folios for the first and 36 for the second), but are similar in that certain sections are difficult to decipher and are totally different in their object.

The 1845 document neither invalidates nor completes the one drawn up in 1807. The provisions of a final will and testament remain common at all levels of the society. The relevance of the present article is linked to the identity the person who drew up the wills, an important figure during her time and who has has permeated the collective memory of Reunion.

Mme Desbassayns made provisions in favour of the indigenous population: “I order that in the month following my death the sum of 2000 piasters, in corn or in money, is to be distributed to the poor in my neighbourhood.”

As a comparison, with the piaster worth 3 pounds, a warehouse of 22,80 m2 constructed of logs with a roof of leaves in La Ravine du Pont, left in his will by Louis Fontaine, deceased, was estimated at about 67 piasters during the inventory drawn up on 9th April 1807 .

These generous gestures were rewards. The situation of the slaves remained unchanged.

She appointed as the executors of her will her sons or sons-in-law resident in the colony at the time of her death, on condition that there were at least two in number. Failing that, she appointed her friends (Antoine Parny, Sainte-Croix etc.), granting them in exchange a gift of 500 piasters in silverware.

Madame Desbassayns’ aim was to divide up her estate between all her children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. The will lists her entire possessions: land, animals and descriptions of her slaves. A separate chapter is devoted to the chapel of Saint-Gilles.

Taking into consideration a steam pump on the estate of Bernica (5,000 F), the money in cash she had on Bourbon island (56,950 F), the income that her descendants were to declare for the estate (104,270 F), the total amount to be divided up amounted to 1,661,350 F.

Her estates, all in the west of the island, were divided up onto several sections.

It consisted of:

– land, the main house and the outhouses (2 wooden pavilions, 4 warehouses, a prison, a hospital, a kitchen for the slaves, a stone kitchen for the masters, a pavilion used as a storeroom, a chicken coop, stone stables etc.); the establishment of the sugar refinery (7 stone buildings used as a storehouse, a syrup refinery, a smithy, a storehouse containing a six horse-power steam pump with an eight horse-power mill and a Wetzell-type sugar refinery, as well as stone stables); a hydraulic machine for the purpose of pumping water from the lower regions of Saint-Gilles up to the sugar refinery, pipes and tanks for the water flow and reception; a house constructed in wood and clay; a stone building used to accommodate the steward; another close to the sea used as a warehouse for sugar waiting to be shipped.

The total was estimated at 502,500 F.

– The 295 slaves attached to the properties were estimated to be worth 428,150 F.

– Finally, the draught animals and other animals (16 mules from Poitou or Buenos Aires, with carts and harnesses, 39 draught oxen, from both Bourbon and Madagascar, with their carts), estimated at à 20,000 F, a herd of 13 oxen and 36 goats, were all recorded for information.

All this amounted to 950,650 F, or 57 % of the general total. Like the other estates, the value of the work force, the slaves, represented an important proportion (45 % of the property in Saint-Gilles).

The land in Saint-Gilles was divided up into several sections: that of Saint-Gilles as such (the Duhal concession), covering the greatest area, included a section measuring 89ha 65a 4ca, appropriate for growing sugarcane, and another section reserved for food crops measuring 54ha 63a 6ca, the remaining part consisting of communal land or non-agricultural land of no appreciable value.

The plot referred to as Emery Mahé, divided up into sugar-cane and food crops, formed an annex to the previous one; that referred to as Léon Parny, parts of which consisted in poor-quality land; the plot referred to as Carrosse (41ha 70a 61ca, and another poor-quality section of 25ha 46a 35ca) ; the plot referred to as Millemont Ricquebourg, of which 11ha 87a 11ca were good-quality land and the rest communal; the plot referred to as Tourangeau, 21ha 36a 79ca of which were agricultural; the plot situated at la Grande Ravine, of which only a very small portion had been cleared and the rest remained as woodland and savannah. All the land in Saint-Gilles covered a total area of over 316 ha.

This consisted of:

– the land in Bernica, with 28ha 49a 5ca of the highest-quality land, with communal land depending on it, as well as three sections located in the hamlet of le Tan rouge (one part of which had been given by Mme Desbassayns’ father to emancipated slaves)

– the plot referred to as Parny, with 5ha 93a 55ca of top-quality land;

– the plot referred to as Cadet, with 31ha 22a 9ca of top-quality land;

– the plot referred to as Châteaubrun, with 9ha 49a 68ca of top-quality land and 4ha 74a 84ca of land of secondary quality;

– the plot referred to as Valère et Virginie, with 2ha 37a 42ca of top-quality land;

– the plot referred to as la Petite Terre, with 6ha 64a 77ca of top-quality land;

– the plot referred to as Hilarion Ricquebourg et Maunier, with 18ha 99a 36ca of top-quality land and 23ha 74a 22ca of land of secondary quality, with communal land attached to it;

– the plot referred to as Massard, with 4ha 74a 84ca of top-quality land and 18ha 99a 36ca of land of secondary quality, with communal land with a wooden warehouse;

– a plot bordered on the lower limit by an agricultural track and to the south by the riverbed of le Bras de Bernica, with about 18ha 99a 36ca of lower-quality land;

– the plot referred to as le Brûlé, used as pasture, consisting of a spur formed by the two branches of the riverbed of Bernica stretching as far as the mountain peaks.

On the estate of Bernica there was a sugar refinery composed of a four horse-power steam pump referred to as ‘Guerry’, with a ten horse-power drum; a copper battery; a Wetzell-type refinery; a stone building used as a sugar refinery and a stone building used as a purging room; one large and one small stone storehouse; a dwelling with a thatched roof; another used as accommodation for the steward; stables, cattle enclosures etc.

In addition, the estate of Bernica itself had a main house constructed in stone, a large stone storehouse and kitchen, wooden dwelling-huts and a wooden kitchen for the slaves, as well as a warehouse with a roof of leaves.

On the same plot stood a wooden house referred to as Bois de Nèfles, in poor condition, a pavilion, a small and a large wooden storehouse and an old stone kitchen;

On the plot referred to as Châteaubrun, a wooden two-storey house, unfinished but in good condition.

The total value of the land, sugar refineries and other constructions was assessed at 266,000F.

The 111 slaves attached to the different plots were worth 151,750 F.

The draught animals and other animals were worth 16,500 F.

The total value of the estate of Bernica was 434,250F, 26% of Mme Desbassayns’ total estate.

A bare plot referred to as Les Dattes; another along the road, with a small plot separated from it by the road of rue Saint−Louis, on which there was a pavilion containing a cotton press, a small plot planted with food-crops situated in front of the main house; the paddy-field of la Fontaine measuring 1 ha42 a45 ca ; the plot referred to as Touchard, bordered along its lower limit by the fresh water of the lake, measuring 17ha, 31a 8ca, including 14ha devoted to sugar-cane; the plot of la Roche Blanche in Saint-Paul, bordered along its lower limit by the fresh water of the lake; and finally, the plot located at la Pointe des Galets, originally part of the estate inherited from her mother, covering about 2ha 37a 42ca.

The total value of these plots was 110,250F, the one of the highest value being the plot referred to as Touchard (60 000 F), the lowest la Pointe des Galets (250 F).

Being part of the estate, as for all inhabitants of the colony, Madame Desbassayns’ 406 slaves “were referred to by their names, casts, ages and professions, with an indication of their market value assessed by the experts”. Listed by family or as individuals, the estimates were based on on their age, profession and physical condition.

By far the greatest majority were Creole (born on the island). This was hardly surprising considering that the slave trade had been made illegal as from 1817, a prohibition confirmed in 1830. In this respect, we can note that certain slaves, Africans on Madagascans, were relatively young, which proves that they were brought into the Colony fairly late on. For example, Paulin−Leroux, African, a foreman aged 26, or Ferdinand, Madagascan, a cooper and shoemaker, sentenced to be chained up for three years.

Most of the first names were ‘conventional’ (Olivier, Geneviève, Candide, Jean Baptiste…). Others reflected highly eclectic sources of inspiration, without there being any indication of who attributed them. Most of these first names were not limited to the slaves belonging to Madame Desbassayns, such as Ainsi, Léveillé, Lindor, Lafleur, Zéphir, Adonis… We can also note Mardi (‘Tuesday’), Mercredi (‘Wednesday’), Janvier (‘January’), but also Sénateur, or Hercule, Olympe, Charlemagne, Vénus, Neptune and Minerve. Bayonne was a name given to one slave, As well est Coblentz (a historical reference?). We can also note Lolo, Barré, Modeste Petite, Henri Petit (a dwarf ?) Ozone, Carbon, Mambo, Catiche, Dominique Macondé, Cafre, Éline de Phanélie (filiation ?) and Roger aka Dauphin.

Mme Desbassayns attributed an annual sum of 1,250 F for the chapel, ‘perpetually’. The beneficiaries inheriting the property were to carry out her will and ensure its application once they were no longer present. If they handed it over to a religious congregation, a high-ranking member of the clergy, or the town council, the amount would be due and paid out to the new owner. Masses would be celebrated there in her memory, that of her husband and members of her family each year and ‘perpetually’. The slaves and poor inhabitants of the neighbourhood, mainly for whose intention she had had the chapel constructed, would be able to attend free of charge. If ever a religious ceremony other than a Catholic one was to be celebrating there, the annuities would cease to be paid.

Her wish was that the chapel should be included in the legacy made to her five children of the estate of Saint-Gilles, the paintings, the sacred vases, the chandeliers, ornaments, carpets, sideboards, benches, armchairs and chairs to be used in the chapel, as well as the marble altar that she had had brought in from France.

These testaments, deeds under private seal, are thus open books giving indications of her estates and other land she owned. In addition to the purely family aspect of the testaments, they are the opportunity to immerse ourselves in the 19th-century colonial society of Bourbon island.