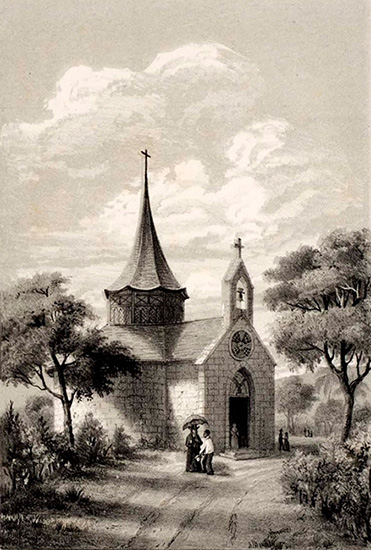

It also highlights the hollow silence concerning the many slaves who built up this wealth for them, with no other recognition than the right to enter the family church, known as the Chapelle Pointu. It wasn’t until the 1820s that the paternalism at the heart of this estate’s management would change, faced with the capitalist conundrum of the budding sugar industry: with the emancipation of slaves, their means of production would vanish…

These two stories of glory and silence, of power and exploitation still haunt the collective subconscious of Reunion Island today.

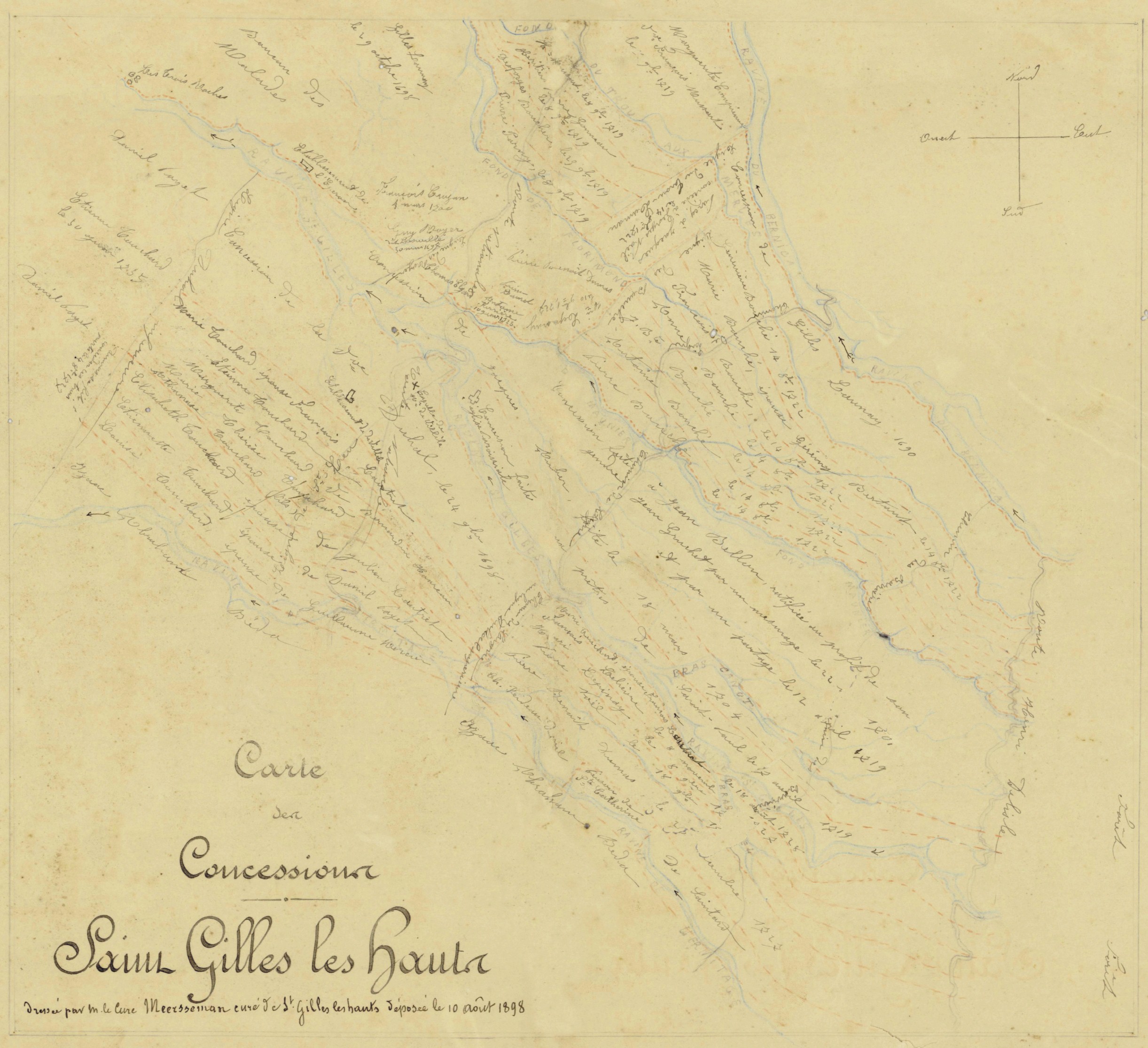

Henri-Paulin Panon Desbassayns had just arrived from the Indies (1762 ), having been awarded the grade of Chevalier de Saint Louis for his exploits, and decided to settle in Reunion and cultivate land he had inherited from his maternal grandmother in 1753, Thérèse Mollet, widow of Duhal (this came from the old Duhal concession from 1698). Henri-Paulin inherited one plot of land in Saint-Paul and two in Saint-Leu, totalling approximately 109 hectares .

He was lucky to benefit from the advice of his good friend Julien Gonneau, also known as Montbrun. This friendship was sealed on 28th May 1770 by marrying Montbrun’s daughter Ombline, barely fifteen years old and the sole heiress of the Gonneau-Montbrun family. As a dowry she had the inheritance of her mother Marie-Thérèse Léger Dessablons, consisting of two plots of land (52 hectares in Saint-Gilles and Grande ravine) and a site in Saint-Paul, all of which amounted to more than 80 hectares.

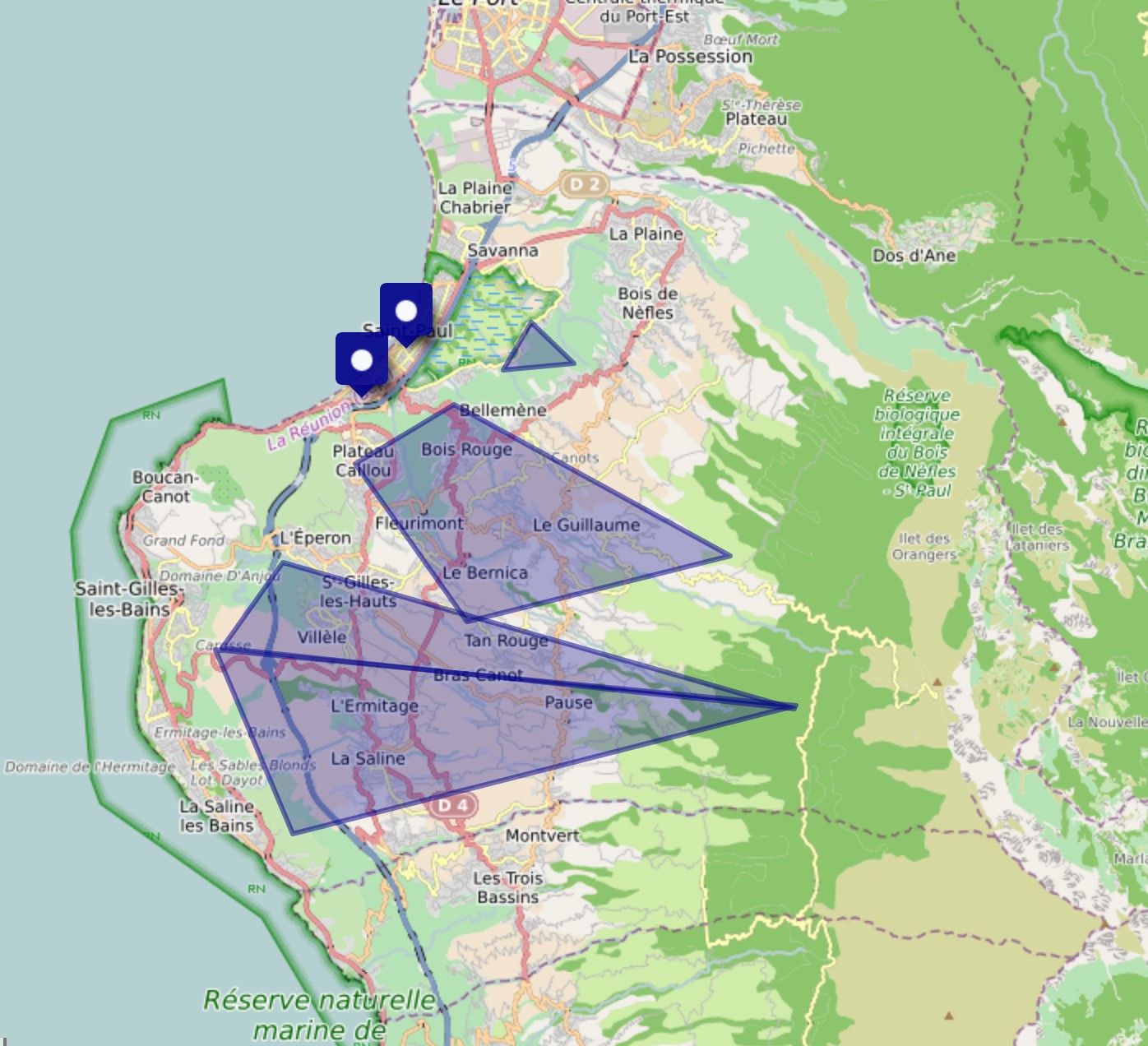

In 1770, this marriage brought together an already large property of nearly 190 hectares, but very scattered, from the towns of Saint-Paul to Saint-Leu via Saint-Gilles, la Saline and Grande Ravine.

From 1770 to 1780, the estate grew by 75%, first in 1772 thanks to the inheritance of Augustin Panon, father of Henri-Paulin (96 hectares in Trois-Bassins) and then in 1776 with the purchase of a plot of land in Bernica (49 hectares) which ran adjacent to land belonging to Gonneau-Montbrun, Ombline’s father. The strategy resulting from Ombline and Henri-Paulin’s marriage was quite obvious: a geographical concentration of land up in the hills of Saint-Paul covering more than 350 hectares.

In a second period from 1780 to 1795, their land-ownership continued more gradually thanks to purchases and auctions, and exchanging of assets. Auction reports show the exasperation of other buyers unable to compete with the might of the Desbassayns. Their land continued to grow with the reacquisition of the old Duhal concession from 1698 (with the exception of the ¼ of the Roux heirs). The 1789 census recorded the estate at 420 hectares. According to the Saint-Paul census, Henri-Paulin was the most taxed inhabitant closely followed by Julien Gonneau-Montbrun.

A few years later, at the turn of the 19th century, just before Henri-Paulin’s death, the Desbassayns estate grew considerably further, covering approximately 750 hectares ; to become the largest estate on the island.

Concerned about the resources and heritage of his nine children (6 boys, 3 girls ), Henri-Paulin Panon Desbassayns granted inheritance advances to his first four children in the form of residential or garden land covering approximately 130 hectares.

After the death of Henri-Paulin on 19th vendémiaire Year IX (11th October 1800), the break-up of the original estate continued. Half of the family property went to Widow Desbassayns, including the main estate in Saint-Gilles (250 ha) with the family residence, half of the estate in La Saline (half of 27 hectares), a third of a dwelling at Bernica (a third of 16 hectares), a third of the land at Carosse (a third of 14 hectares) and half of a garden plot in Etang Saint-Paul, all covering a total of at least 270 hectares.

The other half was divided up among their 9 children (269 ha), after deduction of the advances already handed down . However, this division of land was temporary, with a period of seven years given to the Desbassayns children to determine where they would live and work.

Upon rebuilding the family estate, Widow Ombline Desbassayns started by the selective purchase of land that had been bequeathed to her children as and when they each made their personal choices . The plots of land she bought back were in La Saline, Bernica and especially Saint Gilles and Etang Saint-Paul.

In the meantime, the reshaping of the Desbassayns estate continued, thanks to the inheritance from Julien Gonneau-Montbrun, who died on 9th September 1801, of which Ombline Desbassayns was the sole heir. It initially included the residence in Le Bernica, a site and surrounding gardens on the Chaussée Royale in Saint-Paul. A substantial cash bequest gave Madame Desbassayns the means to pay back her children. This policy of selective buy-outs and the contribution of the Gonneau-Montbrun estate led to the creation of large, consolidated estates that were easier to cultivate, organise and manage. This policy continued between 1810 and 1845 via a dozen real estate transactions (purchases, sales and exchanges). In 1845, the year of Madame Desbassayns’ will, her real estate assets included three domains: St-Gilles, Bernica and St-Paul .

– St-Gilles: the main estate with stone house (195.5 hectares, i.e. 3/4 of the of the old Duhal concession), the Parny/Lefort plots (39.7 hectares), Carosse (86 hectares), Ricquebourg (15.5 hectares), Tourangeau (23.7 hectares) and the plot in Grande Ravine, totalling nearly 400 hectares, of which 277 were easily cultivable and among those, 193 hectares of excellent quality;

– Bernica: 7 plots of land totalling 192 hectares, half of which were in Bernica (with stone house) and at Ricquebourg Maunier;

– St-Paul: 2 plots of land measuring 6000m2 with a main stone house and 4 plots of land with gardens amounting to 23 hectares of sugar cane.

On top of these plots covering 492 hectares, there were also 190 hectares of woods and 1000 hectares of savannah, therefore representing a considerable estate. By 1845, it was no longer the largest property on the island, but still in the top ten. Since the beginning of the 19th century, several large sugar cane estates were established in the east and south of the island.

After the unstable early days of the colonisation of Bourbon, slavery was introduced very gradually in the last decade of the 17th centurye and then became widespread across colonial plantations thanks to a system already put in place in the West Indies as early as the previous century. Made legal in Bourbon by decrees of 1715 and 1718, slavery was governed by a specific version of the Code Noir, enacted in December 1723 . During the period studied (1770-1846), the colony’s management reverted back to the King (1767). At the end of the 18th century, the burning question put to the colonial system concerned the abolition of slavery : voted by the Convention in February 1794, but refused by the slave-owners on Bourbon, this abolition was revoked by Napoleon who re-established slavery in 1802. The secession of Saint-Domingue left a considerable scar, and ways were found to continue the slave trade, despite its abolition in 1817. It was not until 20th December 1848 that slavery was finally abolished on the island, proclaimed by Sarda Garriga. Having died in 1846, Madame Desbassayns never lived through this change.

Without slave labour, the development of any colonial estate was inconceivable, and the Desbassayns estate was no exception to this.

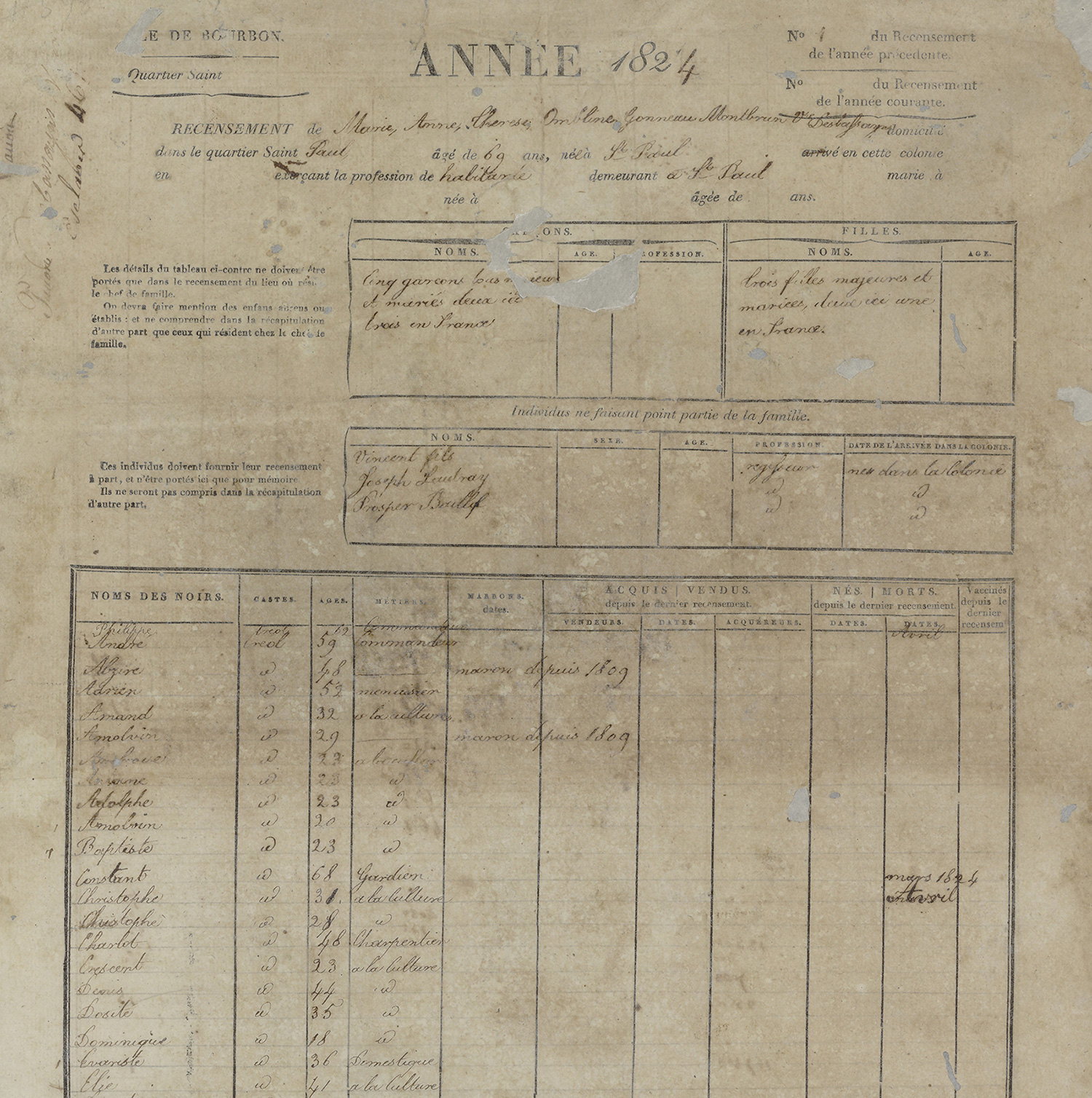

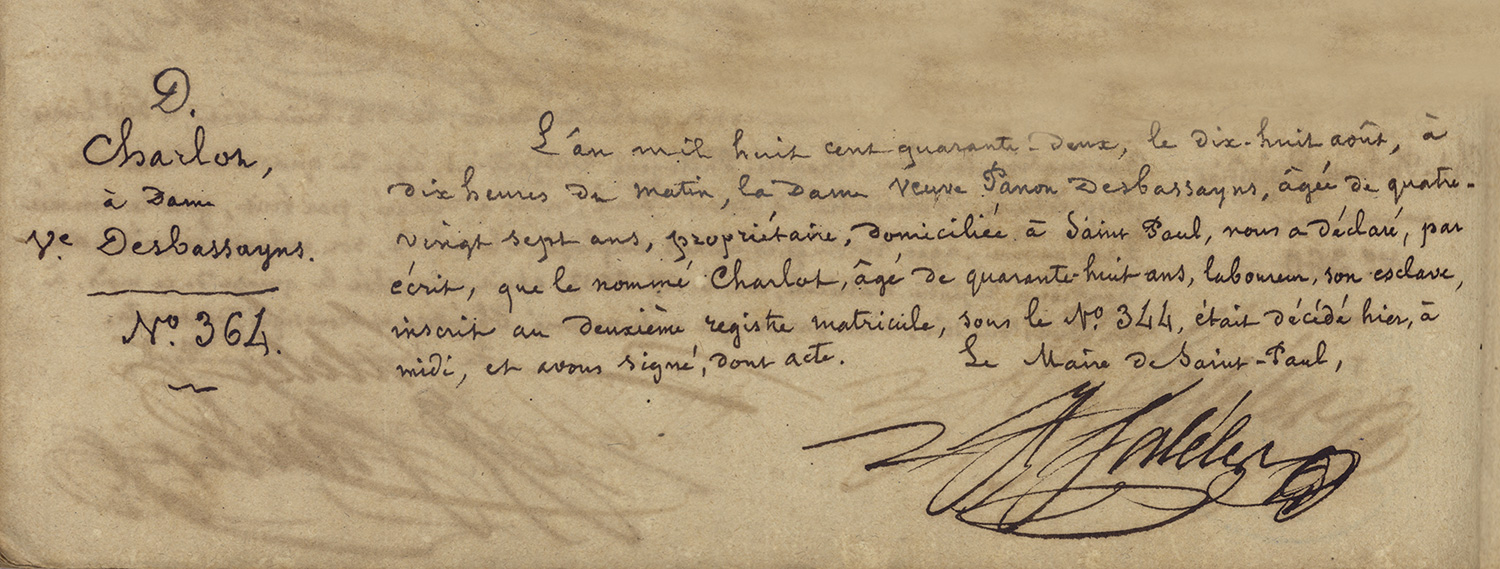

As a ‘movable property’ bought and sold with no interest other than labour, slaves were closely monitored by the administration. Each sale involved a tax and, for historians, the owners’ annual censuses (which became more detailed over time) are a limited means of learning more about the reality of the slaves of the Panon Desbassayns. Other sources included Henri-Paulin’s diary, letters from the family and finally Madame Desbassayns’ very detailed will.

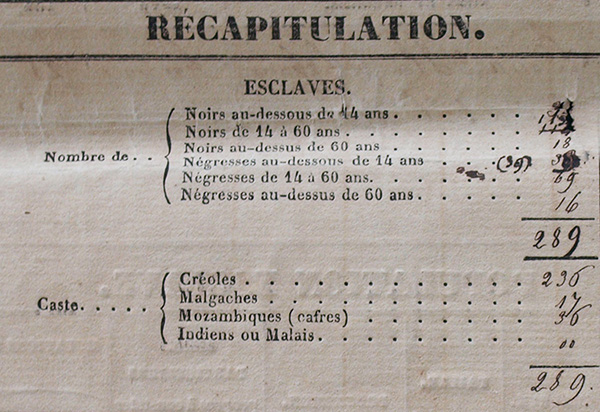

Slaves were identified by a first name (given by the master), then ‘categorised’ according to sex, age, ethnic origin / caste (Creole, Malagasy, Mozambican, Indian or Malay) and occupation. Their numbers were totalled by age groups that would change from year to year .

As the estate grew in size, the number of slaves duly increased. This was particularly true during the period between 1770 and 1800, when the estate tripled in size and the number of slaves quadrupled. From 1807 and until 1846, the numbers remained stable, with an average of almost 440 slaves for an area of about 450 hectares.

| 1770 | 1776 | 1789 | 1797 | 1801 | 1807 | 1813 | 1829 | 1836 | 1845 | |

| Surface area | 190 | ? | 420 | 720 | 270 | 400 | 472 | 469 | 441 | 492 |

| No. of slaves | 80 | 254 | 348 | 417 | 250 ? | 429 | 485 | 462 | 430 | 401 |

The master dominated everything. First it was Henri-Paulin Panon Desbassayns and then his wife, Ombline Desbassayns, who took over from her husband during his travels outside Bourbon and after his death in 1800. At the age of 65, she gradually handed control over to her son Charles-André who formally became the estate administrator on 24th May 1822.

The master was assisted by a supervisor (later several) whose role grew after 1800. He was usually a Creole born on Bourbon or sometimes a colonist from France such as Jean-Baptiste de Villèle, recruited by Madame Desbassayns between 1799 and 1803. In 1836, there were three supervisors to deal with five plantations: two Creoles and one French colonist, Frédéric Mion. In 1845, Sosthène de Chateauvieux, Mme Desbassayns’ grandson, and Auguste Bouché replaced the other two to join Frédéric Mion. These supervisors were in charge of several ‘foremen’, all Creole slaves chosen for their loyalty to the masters, who in turn led groups of slaves.

Running through this chain of command, the specialisation of the slaves’ tasks was key (as seen in annual censuses and Madame Desbassayns’ 1845 will), even creating a second hierarchy, one of values.

At the top of this hierarchy were the residence slaves (house and courtyard) because of their proximity to their masters. These domestic workers served the masters, took care of the children, the housework and the gardening, including sought-after specialities such as cooking, baking, laundry, ironing, and roles as nurse / midwife. They would often travel with their masters from Saint-Gilles to other places (Bernica), into town or even exceptionally when leaving the island (on two occasions, Henri-Paulin travelled to France with 1 or 2 domestics from his house). Their loyalty was regularly tested and rewarded. There were 12 of them in 1807, 19 in 1823 and 8 in 1845.

Below them in the hierarchy came the craftsmen (joiners, carpenters, masons), highly useful for the construction and repair of houses and buildings. Workers in the sugar mill were just as valuable as these craftsman.

Departmental Archives of Reunion Island Collection

Finally, placed at the bottom of the slave hierarchy, came the ‘noirs de pioche’ (‘pickaxe blacks’) or ‘noirs de culture’ (‘plantation blacks’) who worked in the fields. These slaves formed what was called the ‘atelier’ (‘workshop’), often split up into teams and led by a foreman. There were 302 in 1807, 304 in 1815, 310 in 1836 and 297 in 1845 .

The third hierarchy established by the slave system was based on ethnic origin. In order to reduce solidarity, the master made sure the different work teams were a mix of ‘cafres’ from Mozambique, Madagascar and those born on the island (‘Creoles’). A subtle hierarchy was thus established, dominated by the Creoles whose number (and percentage) increased (especially after the abolition of the slave trade) and who the masters favoured.

Slaves had no other job than labour, and discipline was exercised everywhere. Supervisors and foremen would rule by the whip, an emblematic weapon to threaten workshy slaves. In addition, here was a whole array of punishments used, each one depending on the gravity of the slaves’ ‘misdemeanours,’ including escaping, which is mentioned in the censuses.

The human cost of slave labour can be best understood by examining mortality rates: from 3.4% between 1786 and 1789, the rate varied from year to year from 2% to 3.6% between 1807 and 1845. This corresponds to average figures for the leeward region in 1819 which were lower than those for the windward regions of both Bourbon and the West Indies (5%). The life expectancy for slaves at the Desbassayns estate was 49 years old for men and 56 for women. But this was lower for those working in the field: 34 years old for men and 42 for women. Unlike in the Caribbean, these figures did not worsen as the sugar cane industry developed; after 1815, the average mortality rates seem to improve. Our hypothesis is that with the abolition of the slave trade, it made more financial sense to improve slave conditions, and births were encouraged.

Illnesses and injuries due in particular to accidents at work were all detailed in Madame Desbassayns’ will in 1845, but without giving the cause, simply specifying whether the slaves were active or not . This use of the word ‘active’ clearly shows that workers included children, as well as the sick and infirm. This is why we estimate the percentage of inactive people at 5%, corresponding to the percentage of children under 6 years old and the disabled. Moreover, letters exchanged between Madame Desbassayns and her children refer to the role of ‘courier’ carried out by ‘little black slaves’ between the various dwellings on the estate, covering distances between 10 and 25 kms.

The issue of emancipation may shed light on Madame Desbassayns’ (and more broadly her family’s) position of slavery. Would this not be the best way to demonstrate to what extent slave-owners could understand the new social issues that had spread across France since the Revolution? It is worth noting that between 1789 and 1793, Bourbon had about 8,200 whites, 1,000 coloured freedmen and 38,000 slaves.

In the period 1780-1790, Henri-Paulin freed two slaves, Pierre and Apolline (8th April 1783), allocating them a plot of land and livelihood (compliant with regulations of the day). The announcement of the first abolition of slavery (decree of 4th February 1794) was refused by the dignitaries on Bourbon, including Henri-Paulin. At the same time, on 31st March 1794, Julien Gonneau (Ombline’s father) freed 12 slaves, giving them a plot of land in the lower part of St-Gilles and selling them 20 slaves, following a procedure accepted by the colonial assembly.

Having managed the estate since her husband’s death, Madame Desbassayns included a proposal in her will of 1807 to free 12 slaves (complete with resources, including 20 slaves). But this was at a time when there was a very conservative reaction among the colonial assembly, which included her sons Joseph and Charles-André and her De Villèle sons-in-law, and in her final will in 1845, this 1807 provision had been annulled. How can this reversal be explained?

Between these two dates, two slave revolts took place in the west of the island; the first occurred in Saint-Paul in 1809, actually helping the English soldiers to advance, and was only stopped by the English occupiers who would shed blood in the name of social peace. The second rebellion took place in Saint-Leu on 5th November 1811, also quashed in a bloodbath just one month later. The causes? Ill-treatment and the desire for freedom. From then on, fear spread everywhere among the colonists, seriously outnumbered by their slaves (in 1812, Saint-Leu had 5870 slaves, 427 whites and 167 coloured freemen).

In the face of this new threat, Madame Desbassayns doubled her efforts to evangelize her slaves, a move that was welcomed by her children. The favourable opinion of Abbot Macquet who visited the house in 1840, was in itself an admission of a political strategy: “In the house we have just visited (that of Madame Desbassayns) … the Christian family is there in all its fervour. What a consoling spectacle the colony would offer if all its colonists converted their slaves…here, emancipation would not be feared…” In 1845, at the age of 90, the only gift she left to her slaves in her will was the estate’s chapel.

We may imagine that following the death of her ‘progressive’ father, Madame Desbassayns would (in her advancing years) gradually fall in line with the very conservative opinions of her sons Charles-André and Joseph and her son-in-law Joseph de Villèle. Emancipation was no longer an option.

Following the French East Indies Company’s lead at the beginning of the 18th century, the region of Saint-Paul was traditionally a place to produce food, as the island was ideal for replenishing ships stopping off at both Bourbon and Isle de France. The only cash crops grown in this area were coffee, cotton, spices and indigo. Census records show the importance of food crops (for self-consumption and sale) between 1789 and 1845. In the 1820s, maize was gradually replaced by manioc: it was easier to cultivate, more profitable, and was mainly used as food for slaves.

| In quintals | 1789 | 1807 | 1813 | 1823 | 1836 | 1845 |

| Corn | 3000 | 2260 | 6000 | 6000 | 5500 | 1000 |

| Rice | 30 | 150 | 100 | 50 | ||

| Manioc | 3000 | 8000 | 15000 |

This food-producing aspect was further strengthened by the relatively widespread livestock farming for self-consumption, sale and pulling carts (200 goats, 100 pigs, 130 cattle in 1789, and in 1845 these numbers were 53 goats, 40 pigs, 130 cattle, 90 sheep and 32 mules).

As for commercial crops, the surface area for coffee fell from 225 to 10 hectares between 1807 and 1845 and, along with cotton, was replaced by sugar cane after 1818 on the estate in Le Bernica (50 hectares in 1823; more than 200 hectares in 1836 and then 150 hectares in 1845) and also in Saint-Gilles. Coffee and cotton were hit by major weather events, in particular the cyclones and droughts in the years 1806-1807. Experimentation of planting sugar cane in the east of the island by Charles and Joseph Desbassayns was conclusive: sugar cane was more resistant to cyclones and of greater value. But at each step of the way, as her estate developed, Madame Desbassayns would always weigh in to impose her authority, ensuring that a sufficient share of food crops were grown on her land.

As sugar cane production evolved (from 1200 to 4250 quintals between 1823 and 1845), modern techniques were favoured: in 1825 there were 2 sugar mills on the estate, one of which was steam-powered. It was the most modern establishment in Saint-Paul (out of 25 sugar mills in 1827, only one was steam-powered, that of Madame Desbassayns), and thus labelled a ‘model sugar mill’ for the whole west coast, serving as a demonstration site for other landowners in the area. During the 1830s, it benefited from several technical innovations by engineer Wetzell. These technical innovations improved the quality of the sugar and its yield . These improvements were based on existing technology – while not leading to any social change, they did herald the specialisation of certain sugar factory workers, thereby improving their social status. This was clearly an era during which no ‘production means’ would be emancipated!

As for the estate’s profitability, it is hard to be sure. In 1823, total production brought in about 250 000F . Costs for maintaining the estate’s 470 slaves that same year were around 50,000F, i.e. 20% of the total income, and depreciation of the production means as well as the cost materials are unknown. One might estimate that the profit for 1823 was between 100,000 and 150,000 F, which would be 8 to 10% of Madame Desbassayns’ total wealth in 1845.

But beyond agricultural activity, other economic activities (commercial, financial, etc.) also increased the family’s wealth.

The fortune of the Desbassayns family was of course made up of inheritances and the purchase of land (Part I), its exploitation by slaves (Part II), but also by their active commercial and financial activities carried out by Henri-Paulin from 1770 to 1793 in France, and then in turn by his sons in London, Hamburg and the United States, particularly during the period from the Revolution to the Restoration.

The vast estate, including both land and slaves, was a sign of wealth.

In 1777, taxes in Saint-Paul were based on the number of Blacks, revealing that Henri-Paulin Panon Desbassayns was the most taxed individual in the area (1587 livres), followed by Julien Gonneau (1043 livres). Patriotic donations in kind during the Revolution followed the same ranking (by 9th July 1794, Henri-Paulin had provided 4657 pounds compared to 3966 by his father-in-law). By 1820, Governor Milius said: “Madame Desbassayns is ranked highest, as much by (her) virtues as by her immense fortune…. She owns 448 blacks and paid 2537 francs in contributions, and is thus the most taxed person in the colony” . However, Madame Desbassayns’ fortune would soon come down, given the developments in the years to come. In Madame Desbassayns’ will (1845), her total assets were listed at 1,557,080 francs, including 649,750 francs for land and 579,900 francs for her 401 slaves (more than half of her means of production). At the same time, only 3% of Parisians owned more than 500,000 F. Madame Desbassayns’s fortune corresponded to the wealthiest family fortunes of cities such as Lyon, Rouen or Lille in 1846 .

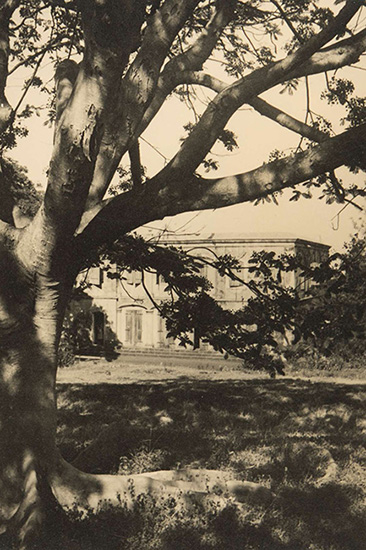

For Henri-Paulin Panon-Desbassayns and his wife Ombline, social success was expressed by a bourgeois, even aristocratic way of life, reflected in the purchases made in Paris by Henri-Paulin during his two trips (Dec. 1784 – June 1786 and early 1790 – early 1793). The couple would regularly invite guests to their vast and opulent residence in Saint-Gilles, as Madame Desbassayns’ will is clear to point out .

But thanks to his knowledge of the world following his time in India, Henri Paulin very quickly grasped the importance of education and networking in order to ensure a sustainable social ascent for the next generation. Education in France and the United States for some, tutors in Saint-Gilles for others, and no efforts were was spared to ensure that the Desbassayns children would become leaders in a changing world .

Education, culture, wealth and their supportive networks brought about matrimonial alliances that gradually added an aristocratic connotation to the family’s reputation. Examples include some of the well-off daughters from De Villèle family who married into old Lauragais nobility (Mélanie married Joseph in April 1799 and Gertrude married Jean-Baptiste in 1803) and also a Montbrun son who in 1809 married Sophie Fabus de Vernan, a member of the Bordeaux aristocracy. The other children were married to wealthy, well-to-do bourgeois families . Over the ten years between 1797 and 1808, Henri-Paulin and then Ombline would be instrumental in strengthening the family’s social status and prestige.

From the outset, the Desbassayns residence (Saint-Gilles in particular, but also Le Bernica and Saint-Paul) was an influential place. The Desbassayns couple and then Madame Desbassayns alone would host the island’s administrators and above all each governor (Governor Milius would be a close friend), travellers (Auguste Billiard), explorers (Lieutenant Frappaz), scholars (Wetzell), writers or clergymen (Abbé Macquet) visiting the island. The letters and accounts of visitors describe the estate’s importance, the opulence of the house, rooms, and everyday lifestyle, underlining Madame Desbassayns’ generous hospitality.

But they also note the influence and political power of the family clan.

In 1768, Henri-Paulin was appointed captain of the Saint-Paul militia, and then promoted to major in 1773, keeping but the prestige of the position and devoting all his time to managing his land , and then after 1770 to his family and to other lucrative commercial activities (arms, trading etc). However, he always showed interest in his neighbourhood and the colony and, in doing so, he built up a solid network based on his economic success, which he increased over time and through his travels.

In fact, any involvement in the public or political affairs of either the colony or Mainland France would essentially be the work of his children and sons-in-law.

In 1791, Julien-Augustin Desbassayns became a member of the first Colonial Assembly created during the Revolution, and in 1799 Joseph de Villèle was elected deputy for St-Benoit, a Conservative stronghold. In 1815, Henri-Charles sat on the town council of Saint-Denis and Jean-Baptiste de Villèle on the town council of Saint-Paul. They were hardline royalists, partisans of law and order and the existing slave system. It was during the Restoration period, under Louis XVIII and Charles X that the influence of the Desbassayns clan was at its strongest. Philippe Richemont was appointed Bourbon’s authorising officer (before becoming administrator of the East Indies); Joseph de Villèle, leader of the ultra-conservative party, was Minister of Finance under Charles X before presiding over the last ministry of this reign during which Philippe (who took part in the commission preparing the ordinance of 21st August 1825 for the reorganisation of Bourbon) was made ‘Baron de Richemont’.

On the island, Jean-Baptiste Pajot became second president of the Colony’s Supreme Council, and Charles-André became a member of the Privy Council of the General Council, and the colony’s president of the commission for the control of Blacks. Because of their proximity with the de Villèle family, the Desbassayns clan gradually built up a reputation as hard-line legitimists. An opponent of the day once declared: ‘Since the Restoration…. actions led by the Desbassayns family together with Mr. De Villèle have brought their disastrous influence and unashamed despotism to Bourbon Island’ .

Under the July Monarchy, the Desbassayns clan were lacking in support, and none of them were elected to the first two legislatures of the Colonial Council between 1830 and 1840. Their return to the third legislature (1838-1840) would be their swan song. Both Charles and Joseph Desbassayns were too attached to the values of the Old Regime and were heavily criticised by a growing part of the urban population who had been won over to republican ideals. The new wealthy sugar producers in the windward regions or in the south of the island, who had adopted the themes of bourgeois ideology, stood out from them and were already preparing for the rise of industrial capitalism.

This article summarises the main findings of a first research project (Master’s degree, Paris I, June 1977): Barret. D, ‘Monographie d’une habitation coloniale à Bourbon: la propriété Desbassayns (1770-1846)’ updated by a recent bibliography and a partial consultation of the Panon Desbassayns collection recently deposited at the National Archives.

This article was written following on from my master’s degree, which has been updated thanks to these 4 books mentioned. But as this is a broader bibliography relating to this period in the history of Reunion Island, one must refer in particular to the various works of Prosper Eve, Sudel Fuma, Hubert Gerbeau, Albert Jauze and Claude Wanquet.

Barret Danielle. ‘Monographie d’une habitation coloniale à Bourbon : la propriété Desbassayns (1770-1846)’. Master’s degree presented at Paris I Sorbonne. June 1977.

Miranville Alexis. ‘Madame Desbassayns. Le mythe, la légende, l’histoire’. Historical Museum of Villèle/ Océan Editions. Dec 2015.

Nida Anne-Marie. ‘Les Panon Desbassayns-de Villèle à Bourbon. Dans l’intimité d’une grande famille créole.1676-1821’. Surya Editions, 2018.

Panon-Desbassayns. ‘Petit journal des Epoques pour servir à ma Mémoire’ (1784-1786). Historical Museum of Villèle. 1991

Wanquet Claude. ‘Henri-Paulin Panon Desbassayns. Autopsie d’un ‘gros blanc’» réunionnais de la fin du XVIII siècle’. Historical Museum of Villèle,

February 2011