While the museum gives us a glimpse of the history of the owners of the house through its diversified heritage, it also reflects the memory of those who worked on the colonial estate, first of all the slaves, from the 18th-century until 1848, followed by the indentured workers who laboured there following the abolition of slavery until the 1930s, and finally, the small-scale settlers, agricultural workers linked to the owners of the property through a contract of service concessions.

Consequently, as regards the history of the island, the essential purpose of the Villèle museum is to give visitors the keys to a better understanding of what defined the plantation society on Reunion and a more precise vision of the basic principle underlying its economy: the system of slavery.

Before presenting the historical Museum of De and the challenges behind its development, it appears necessary to situate this cultural facility within its island context: Reunion Island and the Indian Ocean zone, a vast geographical space that stretches from southern Africa as far as the Australian sub-continent.

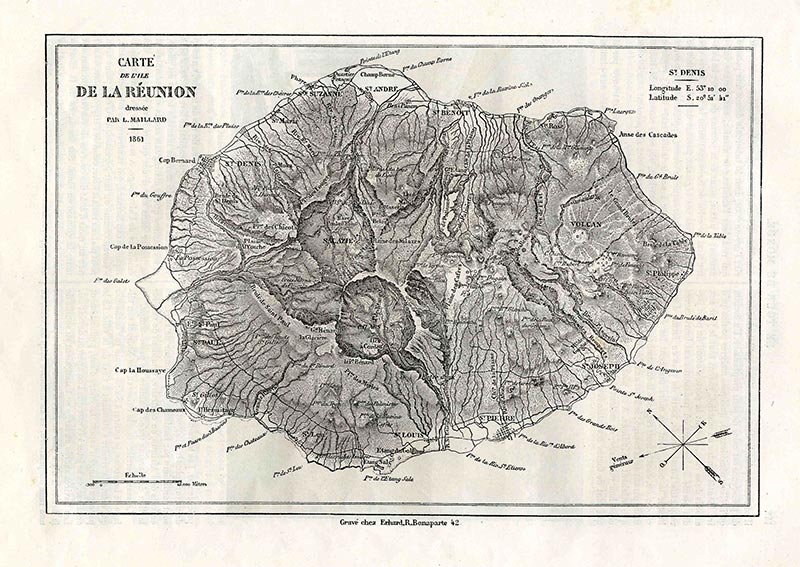

Reunion, formerly called Bourbon island, lies to the south-east of Madagascar, to the north of the Tropic of Capricorn and approximately 10,000 km from mainland France. The island was initially a stopping point on the maritime route for vessels sailing under the French East India Company. The plantation economy developed mainly during the 18th and 19th centuries. The island became a French overseas department in 1946, then, following the French laws on decentralisation of 1982 and 1984, a single-department French Region. Finally, following the signature of the Treaty of Amsterdam in 1997, it has become one of the seven outermost regions of Europe. The island, which covers an area of 2,512 km2, presents extremely mountainous relief, culminating at 3,070m with the Piton des Neiges (fig. n°1). The landscapes are extremely diversified, but three quarters of its area, at an altitude of over 800m, is covered in forest and sparsely populated. The figures produced by the latest census (INSEE, 2011) indicate a population of over 830,000 inhabitants. Reunion is a young island, presenting wide cultural diversity. The rate of unemployment, as assessed by the International Labour Office, is very high: close to 27.2 % of the active population.

The island was only inhabited in a permanent manner as from the 1660s and experienced several phases of settlement. The first French settlers arrived in the years around 1665, bringing with them a workforce from Madagascar. The coffee-growing period, and the development of the plantation economy heralded the arrival of immigrants from Europe, notably French settlers, but also arrivals from countries in the Indian Ocean zone: slaves imported from Madagascar, Africa (in particular Mozambique) and India. Immediately preceding the French Revolution, the island had a population of 46,000, 35,000 of whom were slaves.

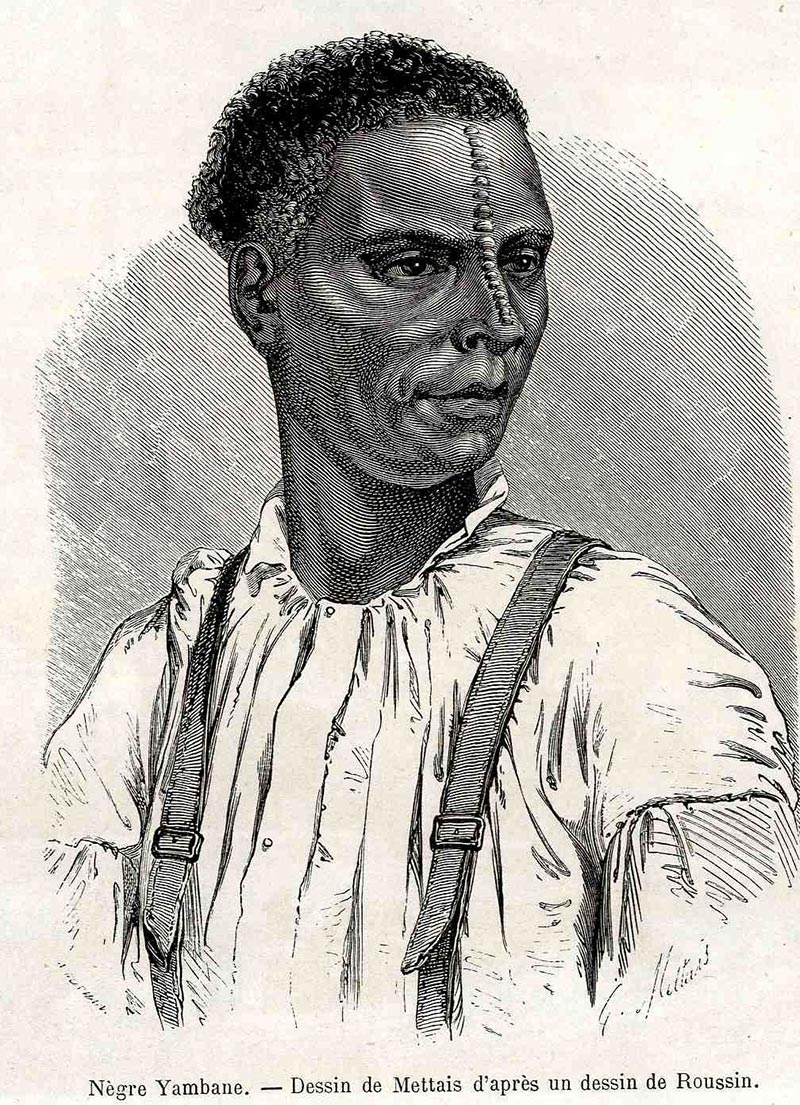

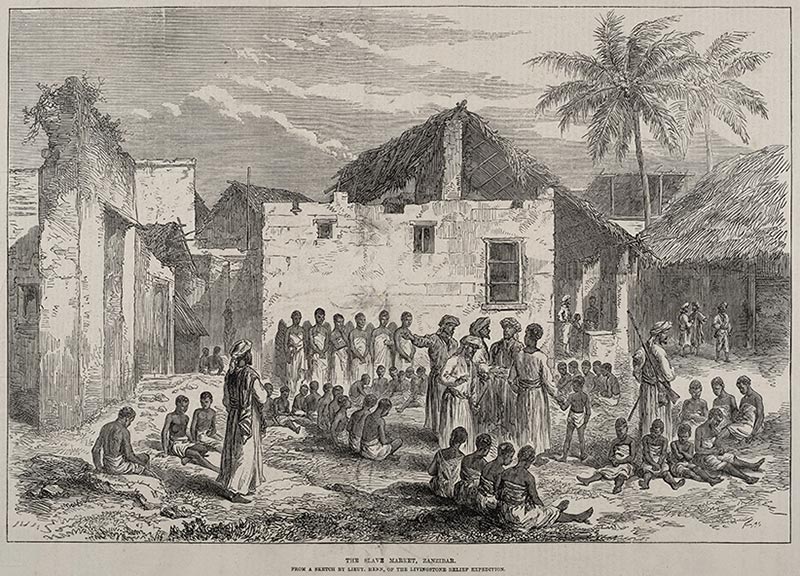

From 1815, with the sugar-cane era and despite the French laws making slave-trading illegal, slaves and indentured workers from Africa (fig. n°2) and India were brought to the island. In 1847, slaves represented 56% of the population (58,308 slaves for 103,491 inhabitants).

After the abolition of slavery and until the 1930s, the island brought in workers under contract or indentured workers, mainly recruited in India but also in Africa, Madagascar, China, Comoros and Rodrigues. In 1881, the population of the island counted 169,493 inhabitants, of whom between 46,000 and 62,000 were indentured workers from India, Africa, Madagascar and China.

Over three and a half centuries, the different population movements have led to the island’s extremely rich cultural diversity. The identity of the Reunionese Creole society, perpetually changing, has its origins in this human wealth, this coexistence of migrants of various origins and their different cultures.

Since the French law on decentralisation, the Departmental Council and the Regional Council of Reunion have both been responsible for the management of cultural establishments, within their legal mandate or as ancillary tasks, in accordance with official policy.

The Departmental Council is responsible for three national museums, two of which are located in the main town of Reunion (Saint-Denis) and one in the west of the island, as well as a place of memory located in the north west.

Situated in Saint-Denis, at the heart of the Jardin de l’État (botanical gardens), former garden for acclimatising plants created in the 18th century by the French East India Company, the Natural History Museum was the first museum to be created on the island. It was inaugurated in 1855 for the purpose of ‘giving young people a taste for science in general, more specifically zoology and mineralogy.’ The colonial authorities of the time presented it as being ‘the sentinel of French ideas in the sea of India.’ Originally a French State museum, it came under the administrative responsibility of the General Council in 1992. Since 2007, the museum has been responsible for the scientific management of a museum annex opened on the site of the former salt beds along the coast of Saint-Leu.

The Léon Dierx Museum and Art Gallery was also set up by the colonial authorities in 1911, at the initiative of two of the island’s authors: Marius and Ary Leblond (pseudonyms of Georges Athénas and Aimé Merlo), with the aim of creating ‘a place of education and memory’ in Reunion, the island being, at the time, considered as ‘a small piece of France in the Indian Ocean’. Collections of modern art were set up under the authority of a committee in Paris consisting of artists, art dealers and intellectuals. In Reunion, the museum also received donations of local art and historical works. The Léon Dierx museum has been essentially an art gallery since 1947, with the arrival of a bequest of works of art made by Lucien Vollard (brother of the famous art dealer Ambroise Vollard), consisting of 157 artistic works representing different modern art movements in France.

The Villèle historical museum was created in 1974, 30 years or so after Reunion became a French department, in order to protect the architectural heritage of a colonial property located in the district of Saint-Paul (fig. n°3) and to provide Reunion Island with a museum representing its history. Since 2007, a place of memory located in the hamlet of La Grande Chaloupe has been annexed to the museum. It consists of former lazarettos, buildings constructed as from the 1860s as places of quarantine to protect the island from epidemics and house the large number of indentured workers arriving on the island. For a number of years now, this heritage site has been the object of restoration work and is considered as an emblematic historical site for the settlement of Reunion.

The Regional Council manages two national museums, as well as two centres of scientific research.

Set up in the early 1990s in a former sugar-processing plant in the district of Saint-Leu (in the the west of the island), the Stella Matutina Museum focuses on the island’s industrial development, notably the history of sugar production. However, for a number of years now, the museum has taken a new direction, focusing on the memory of the population, as well as sugar in general.

Under development for a number of years now, the Museum of Decorative Arts in the Indian Ocean – the MADOI – was inaugurated in 2007 in the municipality of Saint-Louis (in the south of the island).

The Maison du Volcan (volcano activity centre), set up in 1992 in the municipality of le Tampon, close to the island’s active volcano the Piton de la Fournaise and the Kélonia sea-turtle centre, inaugurated in 2006 and devoted to the study of sea-turtles, are two scientific centres also attracting tourists.

One museum project was finally abandoned. The Regional Council elections in 2010 heralded the demise of the project for the MCUR: Maison des Civilisations et de l’Unité Réunonnaise. This was to have been a centre of civilisations and unity in Reunion, an ambitious cultural project piloted by the former elected majority of the Regional Council and reflecting their cultural policy. Like the important international museums set up in the last decade, the project in Reunion was an innovative one in both its conception and architectural design, both a museum of the island’s society and history, as well as a scientific and cultural centre.

The Villèle museum is above all a place of history that, through material elements still in existence today, evokes the evolutions and changes that took place within a colonial estate during a period covering almost two centuries. The museum stages the history of the protagonists of the site, placed in opposition through the policies of the colonial system: on the one hand the masters, settlers or descendants of settlers coming from Europe, more precisely France, and on the other hand the servile population, greater in number and consisting of slaves and later indentured workers brought in from Madagascar, Eastern Africa or Asia.

The former Desbassayns ‘habitation’ (fig. n°4) – a term used in the 18th and 19th centuries in reference to the property or estate belonging to a plantation owner – presents all the characteristics necessary to define and understand the economics of the plantation system in Reunion, both in terms of means of production and agricultural exploitation of the land, as well as the exploitation of a servile population.

Located in Saint-Gilles-les-Hauts, the estate was set up during the second half of the 18th century, from several concessions granted in the 17th century and unified through the will of a rich family of Creole settlers, the Panon-Desbassayns family. Henri Paulin and Ombline Panon-Desbassayns, who had each inherited large plots of land, continued to increase their common estate and extend the limits of their property, which they developed in strips from the coast up (without respecting French regulations concerning the public character of the shore) and as far as the mountain slopes overlooking Saint-Paul, along the limit of the public domain, established at an altitude of approximately 1400 m.

The prosperity of the estate depended on the direct agricultural exploitation of the land, with cotton, and more particularly coffee, grown in the 18th-century, replaced by sugar cane as from the first third of the 19th century.

The development of the territory through agriculture necessitated the use of a servile workforce, mainly consisting of slaves until 1848, Africans (black population), Madagascans, Indians (limited in number), but also Creoles (persons born on the island), then, following the abolition of slavery, contractual workers referred to as indentured workers, also from Africa, Madagascar, but above all from India.

in 1845 the Desbassayns family owned two mansions in Saint-Paul, with 492 hectares of agricultural land and a workforce of 401 slaves.

Following the death of the widowed Madame Desbassayns on 4th February 1846, the estate was passed down to several of her children, and finally on to Céline, one of her granddaughters, married to her cousin Frédéric de Villèle, a nephew of Joseph de Villèle, Minister of Finances under the French Restoration. The latter had married Mélanie Panon Desbassayns on Bourbon island in 1799.

With the crisis affecting the sugar trade as from the end of the 19th century, which intensified during the first half of the following century, in order to conserve the unity of the the estate, the heirs of the Villèle family grouped together in 1927 (fig. n°5), creating a limited company. They contracted a loan, enabling them to invest in equipment and improve the production capacities of their sugar cane. They revised their management techniques, introducing the system of share-cropping, based on the principle of indirect agricultural exploitation of the land: contractual leasing of the land whereby one third of the income goes to the owners and two thirds to the farmers.

Finally, the property was sold in 1962 to a credit company, the Crédit Foncier Colonial. The remaining descendants retained the use of the family house in exchange for a rent, for the duration of a 30-year lease signed in 1971. Two years after their final departure for mainland France, a page of the history of the large sugar estates on the island was turned, marking the end of the Desbassayns-Villèle dynasty.

In order to conserve this remarkable heritage site and set up a historical museum here, in 1973, the General Council of Reunion acquired part of the estate, including the mansion, from the governing board of the company owning the property. The historical Museum of Saint-Gilles-les-Hauts was created in 1974 and inaugurated in 1976.

The museum is also defined as a centre for the interpretation of the system slavery, seen through the emblematic figure of Madame Desbassayns, an absolutely exceptional person who has marked the collective memory of the Reunionese society. She was a Creole lady who managed her two plantations, located in Saint-Paul, where over 400 slaves lived and worked. She did so alone and with an iron fist over a period of more than 46 years, from 1800 (the year her husband died) until 1846.

The character of Madame Desbassayns, a controversial and far from ordinary historical figure, is two-sided, reflecting conflicting antagonisms in the Reunionese society. She is depicted in two antithetical manners, half angel, half demon, both as a Second Providence who administered her family estate in accordance with a paternalistic model and also featured as the incarnation of ‘Granmèr Kal’ (a popular figure from Creole legends, whose facade conceals the figure of a witch), said to have been responsible for the most heinous crimes. With the years, the symbolic representations of Madame Desbassayns have evolved, following the social and political changes taking place on the island and crystallising the uneasiness and the fears of the postcolonial society.

The Villèle museum combines a historical approach to the character of Madame Desbassayns, rooted in the social, political and religious realities of her period, while also taking into consideration the image she represents in the collective imagination of people on the island, a sort of monstrous chimera, paragon of the system of slavery.

In the small private chapel (fig. n°6) constructed close to the main house can be seen the tombstone of Madame Desbassayns, erected on 4th February 1866, when her remains were transferred there from her original burial place in the cemetery of Saint-Paul. While the epitaph engraved on her marble tombstone bears the words ‘Second Providence’, the slab was smashed by a cyclone on 4th February 1932, the anniversary of her death, which, according to popular legend, is material proof of her infamous character.

It clearly appears that with time, the reputation of her as Second Providence has greatly suffered and today, for a large number of Reunionese, the very fact of pronouncing the name of Desbassayns represents a denunciation of the cruelty of the colonial system and the bitter taste of a bygone era, but that will forever be imprinted with the horrors of slavery.

The estate fulfils its purpose as heritage site in several ways, first of all, through the history of the buildings, on the basis of clearly visible traces of the past, in other terms what is reflected by the former constructions conserved in situ and bearing witness to the social, economic and religious organisation of a colonial property.

The mansion, completed in 1788, is based on a classical architectural model imported from Pondicherry (fig. n°7). In the 19th century, it was described as ‘a castle of Malabar Indian architecture’. The mansion is now the main museum space, organised on two levels. The seven ground-floor rooms house the permanent collections, while the four rooms on the first floor are devoted to temporary exhibitions.

The owners’ kitchen (fig. n°8) occupied part of an adjacent building close to the main house, as was the custom on Creole estates. In the holograph will drawn up by Madame Desbassayns in 1845, there is also mention of a slaves’ kitchen, a building that was not conserved and to this day has not been located!

The timber building covered with wooden shingles (fig. n°9), certainly the former bailiff’s accommodation, has been turned into a reception area for visitors and also contains an office, as well as a store-room for the museum’s collections.

The estate also had a hospital, a stone building where the slaves used to be treated and which, until the start of the 20th century, was used as a medical dispensary for people living in the vicinity. Until 1973, they were treated by the last members of the family to live on the property! It was here that a memorial (fig. n°10) was erected and inaugurated in 1996, in honour of the slaves who had lived and worked on the plantation: Africans, Madagascans, Indians and Creoles. The monument is an installation inspired by a document from the archives (census document), listing the name given to each slave by the masters, as well as his or her age, ethnic origin and function. Two years before the celebration of the abolition of slavery, it seemed important to mark, through a symbolic gesture, the presence of the slaves who had lived and worked on the property.

The former storerooms were housed in a long rectangular building now used for various purposes. Referred to as the ‘longère’ (rectangular farmhouse), its eight rooms, more or less converted, now quite simply house various museum departments. These rooms are thus not accessible to members of the public, but it is planned to rehabilitate the building as a whole, in order to create new exhibition spaces devoted to the living conditions of the slaves on the plantation, runaway slaves and the periods of abolition in 1794 and 1848.

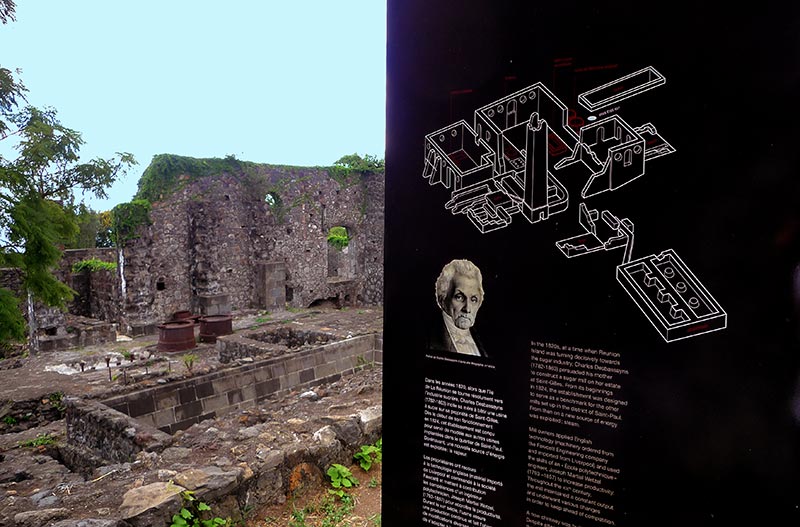

To the south of the main mansion, there are the ruins of the estate’s sugar factory, originally built in 1823-24 and considered by its contemporaries as a model establishment. It was equipped with a steam mill for the district of Saint-Paul (fig. n°11). From 1993 to 1995, the site was restored in the context of a social integration project. The surrounding zone is still not freely accessible, but a project aimed at setting up a trail for visitors is currently being studied, with the purpose of recreating the history of the sugar-factory, both from the perspective of manufacturing techniques for cane-sugar production and the social organisation of its workers.

A private chapel named Chapelle Pointue was constructed on the site by Madame Desbassayns for use by her slaves. The architecture of the original building, put up as from 1841, was somewhat original, of Neo-Gothic inspiration. The chapel, destroyed by a cyclone in 1932, (fig. n°12) was reconstructed the following year. A restoration campaign in 2002-2003 made it possible to replace the interior decoration that had been neglected during the 1933 reconstruction.

It is important to indicate the site of the camp, located outside the museum grounds. It was here that the workers – first the slaves, followed by the indentured workers – were housed, in groups of straw huts. Today the former camp, now a residential village, retains few material traces of its historical past, with the exception of the lay-out of the plots of the oldest houses, as well as the road network. On the other hand, part of the population of the village, consisting of the descendants of slaves or indentured workers, retains very contrasting memories of the de Villèle family. Those who dare break the silence – the topic remains a taboo – express either a strong feeling of resentment or an unfailing respect, tinted with nostalgia and regret, for the former masters of the site. The attitude of each person almost certainly depends on the function occupied by his or her ancestors within the management of the estate.

In accordance with its status, the Villèle museum also houses collections to support the elements of information made available to visitors. It must be admitted that until the 1980s, the museum exhibited a more or less coherent collection of objects and documents, evoking different aspects of the island’s history, but without truly treating the issue of slavery which, it should be pointed out once again, has left few material traces.

The collections are divided up into three groups: the original collection, the repository and the acquisitions.

– The original collection was set up when the museum was created in 1974. A stock of decorative objects and furniture was bought from the family by the General Council, making it possible, still today, to evoke the way of life of a family of Creole plantation-owners. These objects form the permanent exhibition, on the ground floor of the former residence (fig. n°13). These reflect the living conditions of the masters, but not those of the slaves!

– The second group is the repository, encompassing a selection of the objects deposited in the museum and collected with the aim of opening up a historical department in the Léon Dierx museum and art gallery, when it was created in 1911. The objects collected, donated by the island’s important families, have been relegated to the shadows of the museum reserves since 1947, when 157 works of modern art donated by Lucien Vollard arrived on the island. We can note that these objects include a muzzle-loading gun given to Mussard, a fearsome hunter of runaway slaves well known to the island’s population.

– The museum acquisitions concern diverse objects collected with the aim of creating a historical museum in the 1970s: models of ships of the French East Indies Company, coins (treasure found on the island) or china objects of the French East India Company donated by an association set up to develop museums in French overseas departments and territories (ADMOM). The aim of the collection was to reflect French colonial expansion.

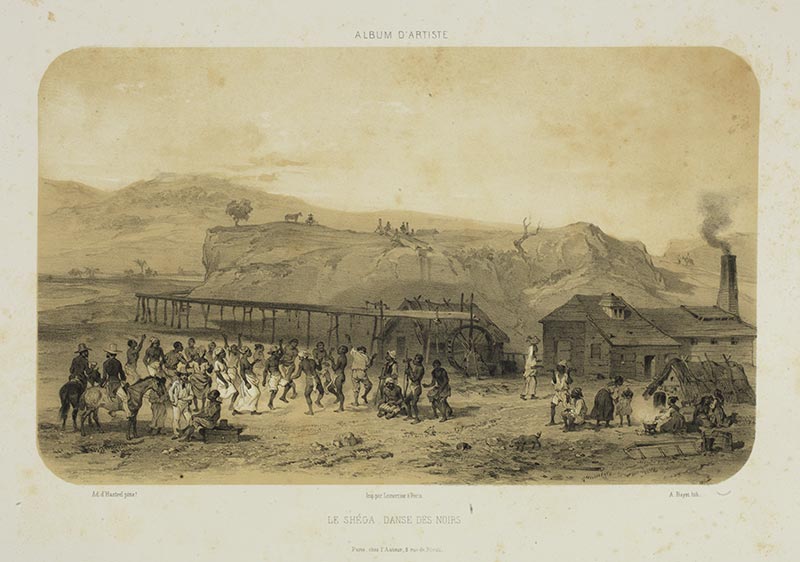

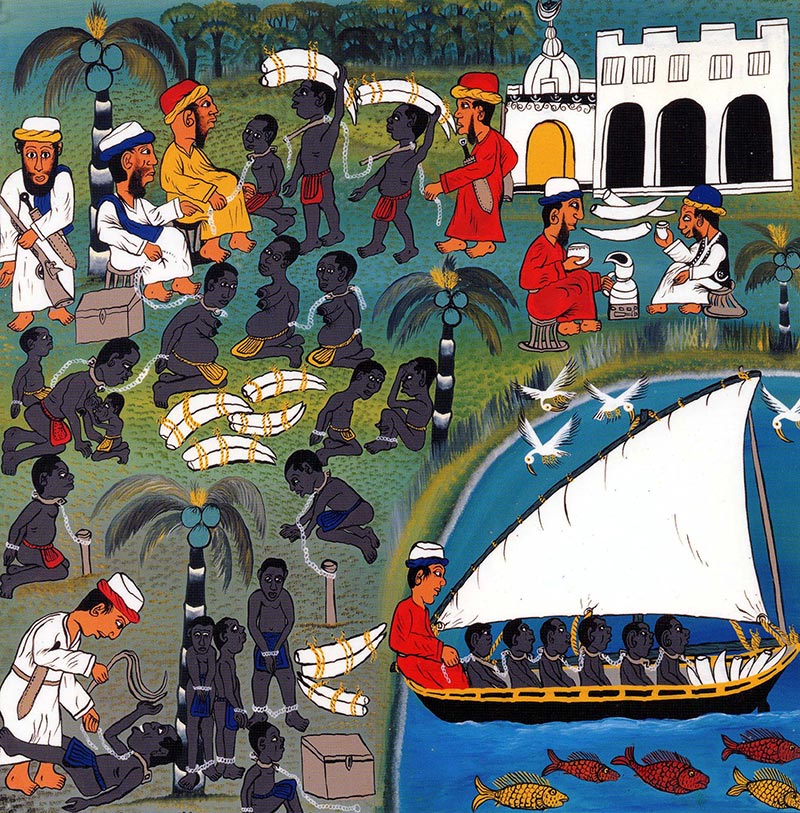

– It was in the 1990s that the Villèle museum decided to diversify its acquisition policy. First of all, it seemed appropriate to reinforce its existing collections, notably the historical section, through the purchase of iconographic documents and works treating various topics: French colonial expansion, the plantation society, but also the slave trade and slavery in Reunion (fig. n°14) and in Indian Oceans countries and islands. (fig. n°15).

– The creation of new collections has notably made it possible to include contemporary art in the museum collections, evoking certain aspects of the history of oppression or giving access to the cultures of countries in the zone that contributed to the settlement of Reunion. Thus, the museum has acquired artistic works from Tanzania, representative of the Tingatinga movement (fig. n°16), drawings characteristic of the Madhubani tradition (from the region of Bihar in the north of India), sculptures created by Makonde artists from Mozambique, a collection of photographs by Dityvon taken during a stay in Zanzibar and creations by artists coming from or working in Reunion: Wilhiam Zitte, Antoine Du Vignaux (fig. n°17), Ann Marie Valencia, Marie-Chrystine Miara, Nelson Boyer etc.

– Finally, in 1993, the museum undertook the conservation of machine parts and tools from the former sugar factory (fig. n°18), objects found scattered around the property or discovered when carrying out clearing operations for restoration work on the factory site. These archaeological remains have been the object of an inventory and an identification index, which includes sketches and photographs. Some of the objects forming part of the collection require important restoration work, to begin at the end of the year.

Since the 1990s, the museum has been granted various funds enabling it to carry out its educational role and that of disseminating knowledge to the public. Without extensively developing the content of the actions planned and details of implementation for each, we can indicate a few priority axes:

– The cultural action of the museum’s educational department and reception staff is a determining element when it comes to mediation for school groups and leisure centres. This includes the production of pedagogical tools, welcoming teams of school teachers, as well as creative events.

– The definition of a policy of regularly organising temporary exhibitions makes it possible to diversify the cultural actions of the museum, as well as producing tools for analysis and acquisition of information, thus enriching the content of the museum and, notably, facilitating a reflection on different aspects of the issue of slavery: genealogical research, the status of women, living conditions and evoking ‘cafritude’ (African and black identity).

– Despite the lack of space, an area has been set aside for the setting up of an embryonic specialised library, intended to be developed. It mainly consists of works devoted to slavery, indentured workers and the cultures of countries in the Indian Ocean zone. En 2011, the collection was enriched through an important donation of antiquarian books about East Africa, travel narratives and accounts of exploration expeditions and religious missions.

– As well as publishing catalogues of temporary exhibitions, this year the historical museum has launched a publication entitled Collection patrimoniale / Histoire (Heritage / Historical collection), the objective being to ensure wide dissemination of information about Reunionese society, provided by researchers from the academic world, with a focus on the quality and and diversity of the iconographic documents conserved in heritage structures, notably the Departmental Archives and the University of Reunion. The first work published, Henri Paulin Panon Desbassayns. Autopsie d’un gros “Blanc” réunionnais de la fin du XVIIIe siècle is a biographical study of Henri Paulin Panon-Desbassayns written by the historian Claude Wanquet.

– While the historical museum appears to be a temple of conservation of the past, it also focuses on producing archives for the future. Consequently, the creation of an audio-visual collection (fig. n°19) is a response to the necessity to record the important events of the museum, as well as enriching the museographical message, notably during temporary exhibitions, while recording accounts from witnesses of past events, knowledge or know-how.

– Academics, historians, anthropologists and associations are regularly consulted on their field of study and invited to take part in research projects at the Villèle museum, creating a true informal scientific committee, functioning as a network.

– The signature of international agreements with cultural institutions located in the Indian Ocean zone is also a perquisite for any cooperative project. This was the context for two exhibitions organised by the museum: one entitled Dominique Macondé, presented at Saint-Gilles-les-Hauts (fig. n°20), was the fruit of scientific research carried out in partnership with the national museums of Mozambique; the other, an event co-produced in 2010 with the French Institute in Pondicherry, presented to the Indian members of the public the links that existed between India and Reunion, through the prism of the history of indentured labour.

The museum of a site, a museum of collections, a museum of the plantation economy, a museum for discovering the cultures that gave birth to the Creole identity, the Villèle museum has yet to forge its identity, combining all these facets. Today, the museum does not explicitly reflect the history of slavery, but should, in the future, more clearly assert this objective, tied to its historical dimension. The museum is also taking up the challenge of offering a museographical project adapted to the profile of its buildings, which will thus be able to reveal the grey areas of their history. Without claiming to be the exclusive historical site on Reunion island and without vindicating such a monopoly, it is undoubtedly one of its most emblematic representations and, a fortiori, remains an essential site for the memory of slavery.