Arab trading posts had existed there since the 8th century. According to Ibn Battouta and Chinese merchants, these Arab towns were prosperous in the 14th and 15th centuries. In the 16th century, the Portuguese disrupted this trade, even seizing some towns: Quiloa (Kilwa), Zanzibar; Malindi, Pate, Monbasa, and even the island of Socotra for a certain time. The trading posts established in Mozambique and Sofala were the focal points of this Portuguese Contra Costa.

In the 17th century, raids from Turkey and Arabia (mainly from the Oman region) combined with local revolts, restricting this domination. The 1698 fall of Fort Jesus in Mombasa marked the end of the Portuguese ‘suzerainty’ to the north of Cape Delgado.

In the 18th century, the French first went to trade with the Portuguese to the south of Cape Delgado, before attempting to trade with the Arabs. During this century, the political situation along this coast remained tense and the Portuguese continued to support the local Arab governors in their fight against the suzerains of Oman. The merchants from the Mascarene Islands either benefitted or suffered from this situation: they were all strangers on the African coast and had to make compromises with everyone.

From 1770, the average number of ‘Kaffirs’ (an Arabic word that means ‘infidel’) disembarked was five times higher than the number of slaves brought from Madagascar. This trade was about to take a new turn, with both royal and private ships sailing there. Weapons from mainland France also played a role.

Both regions will be studied separately here: first the Portuguese territories, then the Arab trading posts, since the commerce took on a different form in the two regions.

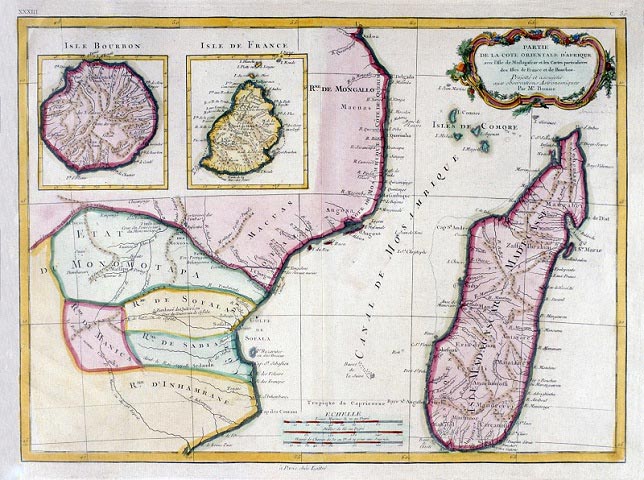

The Portuguese still had control over the coast between Delagoa Bay and Delgado Cape. Their territories as a whole formed the General Capitancy of Mozambique.

Mozambique and Sofala were the two most important. However, a lot of French traders sailed to Ibo in the Quirimba islands, as it had the advantage of being far from the authority of the General Capitancy. The French also visited “Yanbanne” (Imbano), “in front of the Sena river” (the mouth of the Zambezi), “Fernand Veloze Bay”, Quelimane and other river mouths.

During this period, the Portuguese trading posts were completely decadent and “terrifyingly filthy” according to a common saying. The town of Mozambique was the embodiment of this decline: there were very few shops, the market was just a area of dried mud, women were crouching or lying on the ground waiting for potential customers, bunches of bananas lay scattered on the ground and in the harbour, next to the Portuguese rowing boats, were French ships loading their human cargo.

The post of Ibo was similarly decrepit: In 1802, Garneray described “a cluster of dark airless huts haphazardly scattered here and there, with pitiful poorly maintained gardens (…) A derelict house with a first floor, no more than a hovel, served as the governor’s palace.” Certain captains did not go through the Portuguese, but traded directly with the ‘indigenous’ people in places known to them alone. The French did not seem to show much interest in other products from Mozambique, such as ivory (‘morfil’).

Following British historians, it is possible to assert that the Mascarene Islands were the main destination of slaves from this Portuguese colony.

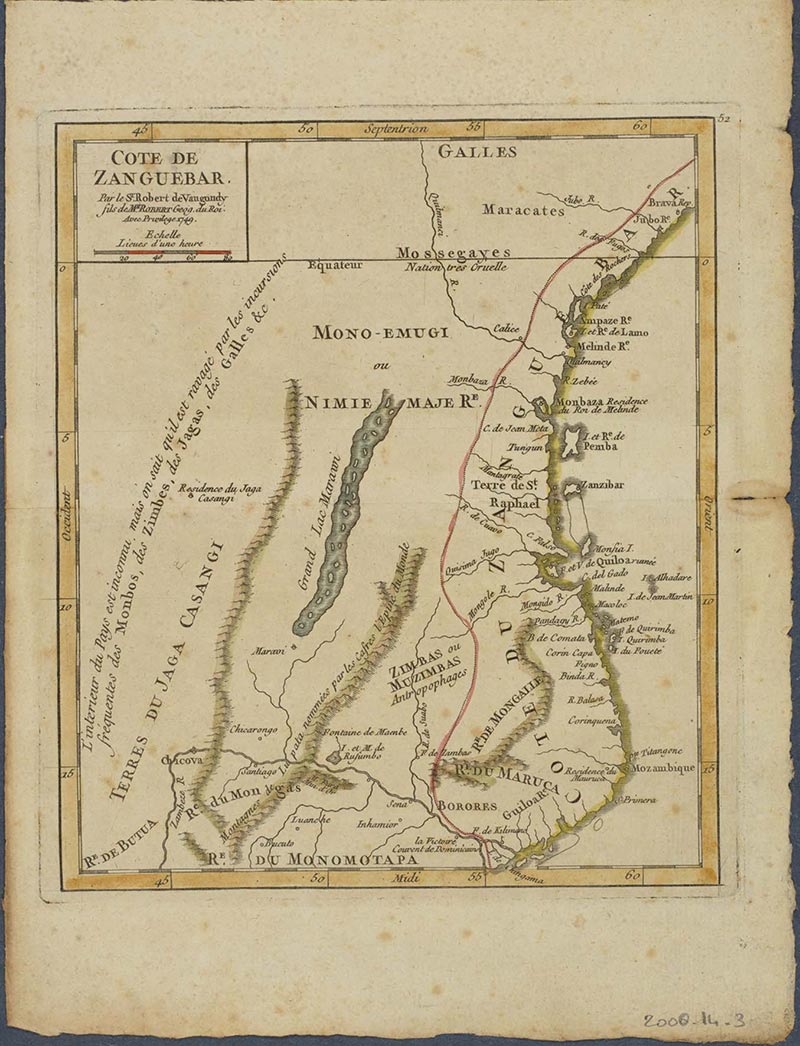

To the north of Cape Delgado, up to the Gulf of Aden, stretched the “coast of Zanguebar. It was under the domination of the Sultan of Muscat. It was mostly a formal suzerainty: in the 1770s the Sultan of Kilwa considered himself to be independent (…)”

In Zanzibar in 1804 “I saw French men arriving and going to the government of the island with an order from the Sultan to allow them to trade freely; their undertaking was unsuccessful because of all the limitations they encountered and everything proved to me that the orders of the Prince would not be carried out in Zanzibar as long as our government imposed protection for our trade in this area” wrote a certain Mr Dallons to Decaen, the Governor General of Bourbon island and the Île de France.

Around 1785-1790 the traffic along the coast of Zanguebar increased, at the expense of that from Mozambique, as the slaves were cheaper and the provisions were more abundant.

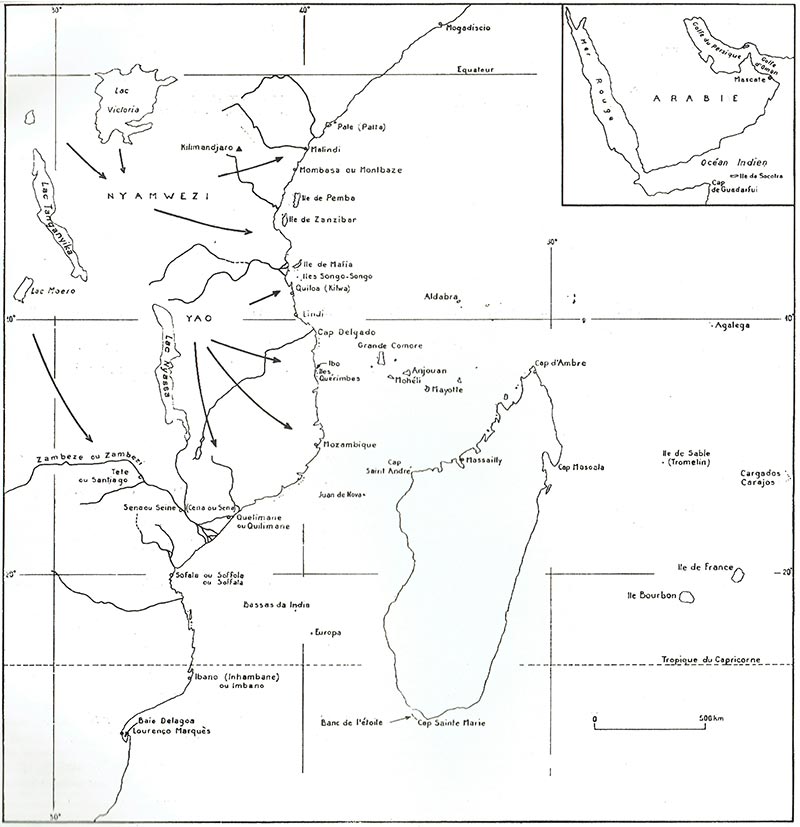

From the south to the north, the French bought their slaves from the posts of Lindi ‘Quiloa’ (Kilwa), Mafia, Zanzibar, Pemba, ‘Montbase’ (Mombasa), Malindi, ‘Pate’ (Patta) and Mogadiscio. Some of these, such as Mogadiscio and Pate, were rarely visited, while others, such as Mombasa, Pemba, Malindi or Mafia, were experiencing local conflicts that disrupted their trade. Eventually, traders from the Mascarene Islands mainly sailed to the Kilwa Islands and Zanzibar.

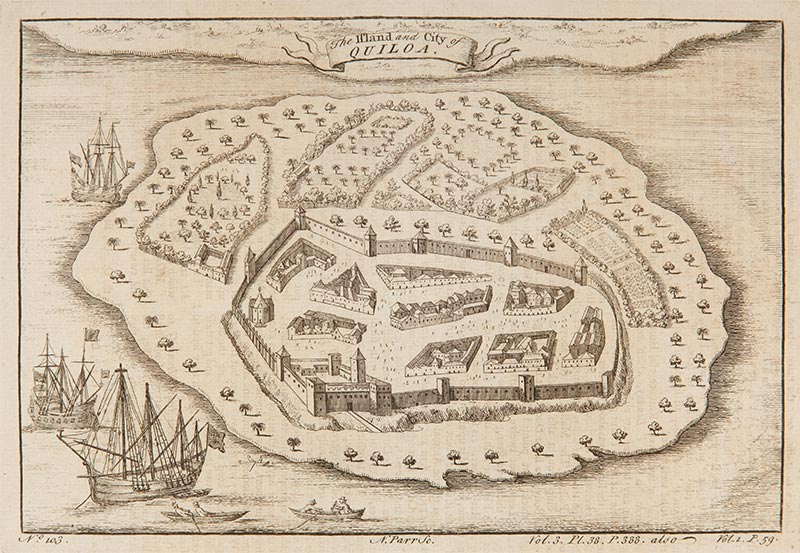

Between 1770 and 1794, Kilwa was the Arab trading post the most frequently visited by French traders; it was “the slave trading warehouse for the entire Zanguebar coast.” Around 1785-1790, almost 1,500 slaves were taken to the Mascarene Islands. In the 1770s, the number of slaves taken reached several hundred since, in 1776, a ship-owner from the Isle of France, Jean-Vincent Morice, had signed a contract with the sultan: “We, king of Kilwa, Sultan Hasan, son of Sultan Ibrahim, give our word to M. Morice, Frenchman, that he shall be given 1,000 slaves each year, at the price of 20 Piasters and that he shall make a present of 2 Piasters for each slave. Nobody shall be allowed to trade slaves until he has received his slaves and wishes for no more. This contract is established for one hundred years between him and me. As a guarantee, we offer him the fortress, where he can set up the canons he wishes, along with his flag (…)’.

This emphyteutic agreement, almost one-sided, can be explained by the fact that Mr Morice offered the services of a surgeon to the Sultan, as well as the desire of the latter to protect himself from Muscat and Zanzibar. The warehouse could have given “to the Isles de France, Bourbon island and the Seychelles the safest, the most abundant and the cheapest means to rapidly increase their slave population and, therefore, to raise them to the desired level of prosperity,” added Mr Morice’s friend Mr Cossigny, at the time the King’s engineer in Port-Louis. Unfortunately, this extraordinary project never saw the day: even though the Naval Minister (Mr Sartine) appreciated Mr Morice’s idea, he didn’t pursue it, as the American war of independence had priority over men and funds from 1778. Mr Morice went back to Kilwa in 1777, as did others, such as Crassons de Medeuil in 1784-1785 and Curt around 1790, who all wished to establish another alliance treaty between the Sultan and the King of France, but little interest was shown by mainland France.

Many ships from the Mascarene Islands continued to sail there until 1794; the traffic picked up again somewhat in 1801 but, in the following year, Zanzibar seemed to find greater interest in the eyes of the traders.

Around 1792, the island of Zanzibar had already been recognised as the most suitable place for the slave trade, so much so that the traders already foresaw it replacing the post of Mozambique. However, the various revolutionary events delayed this development. Ships from the Mascarene islands started coming regularly only from 1802.

Zanzibar was “the main colony of the Imam of Muscat”. Each year, thousands of slaves were taken to the Persian Gulf, Arabia and India. French traders then started to take part in this traffic, despite the obstacles placed by the eunuch-governor and the head of Customs.

If the island offered “abundant provisions, rice, maky, millet, coconuts, fruit, cows, goats and poultry at very affordable prices” and, despite the complaints from Mr Dallons (“this commerce that ruins the French”), we know, from Garneray, that “this market provided an abundant supply of ebony” and that prices were not higher than anywhere else.

In the Arab trading posts, the French slave trade was only secondary, while it was of first importance in the Portuguese posts, as most of the slaves were destined for Muslim territories. The question is: where did these slaves come from and by what means were they brought to the coast? Here, we must remain reserved: few documents exist. There are just a few elements here and there that can help find an answer.

Long distance commerce existed long before the slave trade: ivory and metal objects went from one village to another.

By the end of the 17th century, the Yao people, in the north of the Mozambique, started trading beyond their borders. They made contact with tribes that were already trading along the coast and soon travelled there themselves. They became the most important slave traders in eastern Africa, bringing their prisoners to the posts of Mozambique, Kilwa, Ibo and Quelimane.

Further north, the Nyamwezi people served as intermediaries, but to a lesser extent, only making an important contribution as from 1800 or so.

The activities of these two populations could provide an explanation for the fact that most of the prisoners came from the Nyassa Lake region and the west of Victoria Lake. It would also imply a form of central organisation, to ensure regular expeditions.

Further south, beyond the Zambezi, the system seems to have been different. Brokers, ‘the Patamares, similar to the Pombeiros in Angola’, travelled to the hinterland to find slaves. Tete on the Zambezi was the trading post the furthest inland possessed by the Portuguese. From there, it seems that at the end of the 18th century, goods were exchanged for slaves up to the area of Lake Moero, territory of the King Kazembe,.

The arrows on the explanatory map thus express only working hypotheses.

In conclusion, it seems that this slave trade was individualised in both space and time. Although we might think it to be completely over, nothing could be less certain. Anyone who travels to Mauritius, Reunion island or the Seychelles and walks around the streets of Port Louis, Curepipe, Saint-Denis, Saint-Paul or Victoria, or goes to the sugar cane fields at harvest time, or looks at small villages here and there will see that the faces reflect the diversity of the population and that Africa is still very much present.

Some authors have tried to identify responsibilities, the “sins of the fathers” wrote the British historian Pope Hennessy, but can we really set ourselves up as judges? The slave trade was a product of the spirit of its time.