In 1881, the ‘Djamila’, a dhow flying the French flag, was captured by the British Navy off the island of Zanzibar along the east coast of Africa with 94 slaves on board. The documents presented to Her Majesty’s officers by the ship’s captain were in order. The ‘Djamila’ was legally sailing under the French flag. The documents had been issued in Mayotte, a French territory since 1841. The vessel may have been headed for Reunion, the Comoros or Madagascar. The captain and the ship-owner were in fact from Mayotte and Nossi-Bé. In application of confidential Franco-British agreements signed in 1867 pertaining to visiting rights concerning vessels involved in the slave trade, the ship, its crew and the slaves were very quickly entrusted to the captain of the vessel ‘Laclocheterie’. The latter, one of the ships of the French Indian Ocean Naval squadron, was, amongst its other missions, tasked with repressing the slave-trade. The owner and captain of the ‘Djamila’ were then taken to Reunion, where the criminal court of Saint-Denis sentenced them to two years in prison and a 50-franc fine. The dhow was set alight and the slaves were “freed”. They were possibly taken in by a religious mission or recruited as ‘indentured labourers’ on one of the of the island’s plantations. The mystery remains buried deep within the silences of archives…

Far from being an isolated anecdotal event, the incident, revealed by British parliamentary sources, reflects the thriving character of the trade in the western Indian Ocean during the second half of the 19th century and demonstrates the important role played by French dhows in the continuing slave-trade, a role far from exclusive, however, despite the image put across by London. It also highlights the attempts – at times successful – made by both the French and the British authorities to combat the trade.

Thanks to the work carried out by historians, we can today estimate that between the 15th and 19th centuries, the Atlantic slave-trade involved the deportation of 12 million human beings. The trade continued to prosper throughout the 19th century, in spite of being abolished by the British (1807), the Americans (1808), and the French (1817). 3.9 million persons are estimated to have been victims of the trade between 1800 and 1866. The trade, exceptional in the history of humanity both regarding its character and scale, did, however, progressively die out after the American Civil War (1861‑1865) and following the abolition of slavery in Brazil (1888). Yet, though the trade was definitely in decline, in the western Indian Ocean, it was at its peak between 1860 and 1890.

Despite its importance, for many years little was known about the activity. This absence of information has gradually been offset through research carried out by historians worldwide during the past forty years. The lack of information is partly due to the largely incomplete character of the archives left behind. Contrary to the Atlantic trade, for the western Indian Ocean, it is virtually impossible to assess precisely the number of men, women and children who were its victims.

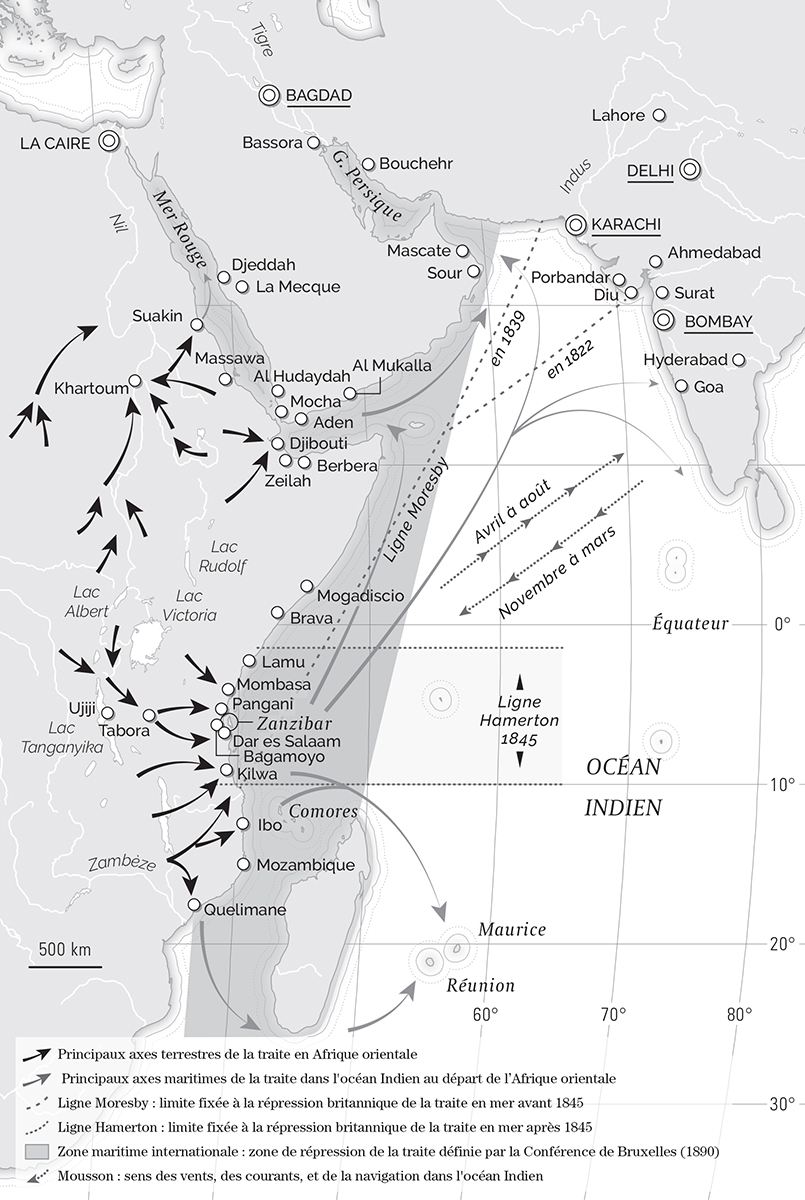

However, researchers now consider that we can have an idea of numbers by focussing on three major centres on the east coast of the continent: the Horn of Africa, East Africa and Mozambique. For East Africa, the best-known of the three regions, it is estimated that 100,000 persons were victims of the trade in the 17th century, then close to 400,000 in the 18th century. Between 800,000 and over 2,000,000 men, women, and children were traded in the 19th century. During the latter period, close to half of them were deported solely along the coast of East Africa, while the remaining number suffered the terrible shipments to the Red Sea, Arabia, the Persian Gulf, the west coast of India, as well as to the Comoros, Madagascar, Reunion, Mauritius and the Seychelles. It is estimated that between 1500 and 1850, European traders, for whom we have more precise records in the archives, seized between 950,000 and 1.2 million persons from East Africa. From the late 1850s until 1873, about 15,000 to 20,000 Africans were captured on the continent each year, then taken to Zanzibar to be sold by traders who were mainly Swahilis, or from Arabia or Persia.

85 % of these slaves were sent to the plantations in the Mascarene archipelago or along the coast, while the remaining 15 % were shipped to the Persian Gulf or Arabia. Elsewhere, in the Mozambique channel, 437 200 slaves are considered to have been transported to Madagascar between 1800 and 1865. In the Horn of Africa, the slave trade reached a ‘peak’ between 1825 and 1850 (150,000 to 175,000) for a total of 500,000 persons over the whole of the century. In the Mascarene islands, it is estimated that a total of 200,000 human beings were traded over the whole of the 19th century.

Finally, we can emphasise that “in total, taking into consideration the other regions [India and south east Asia] and slaves other than Africans, the cumulated number of human beings exchanged within the Indian Ocean space throughout the centuries [from Antiquity to the 19th century] was way over the 10 to 12 million slaves shipped to the Americas.”

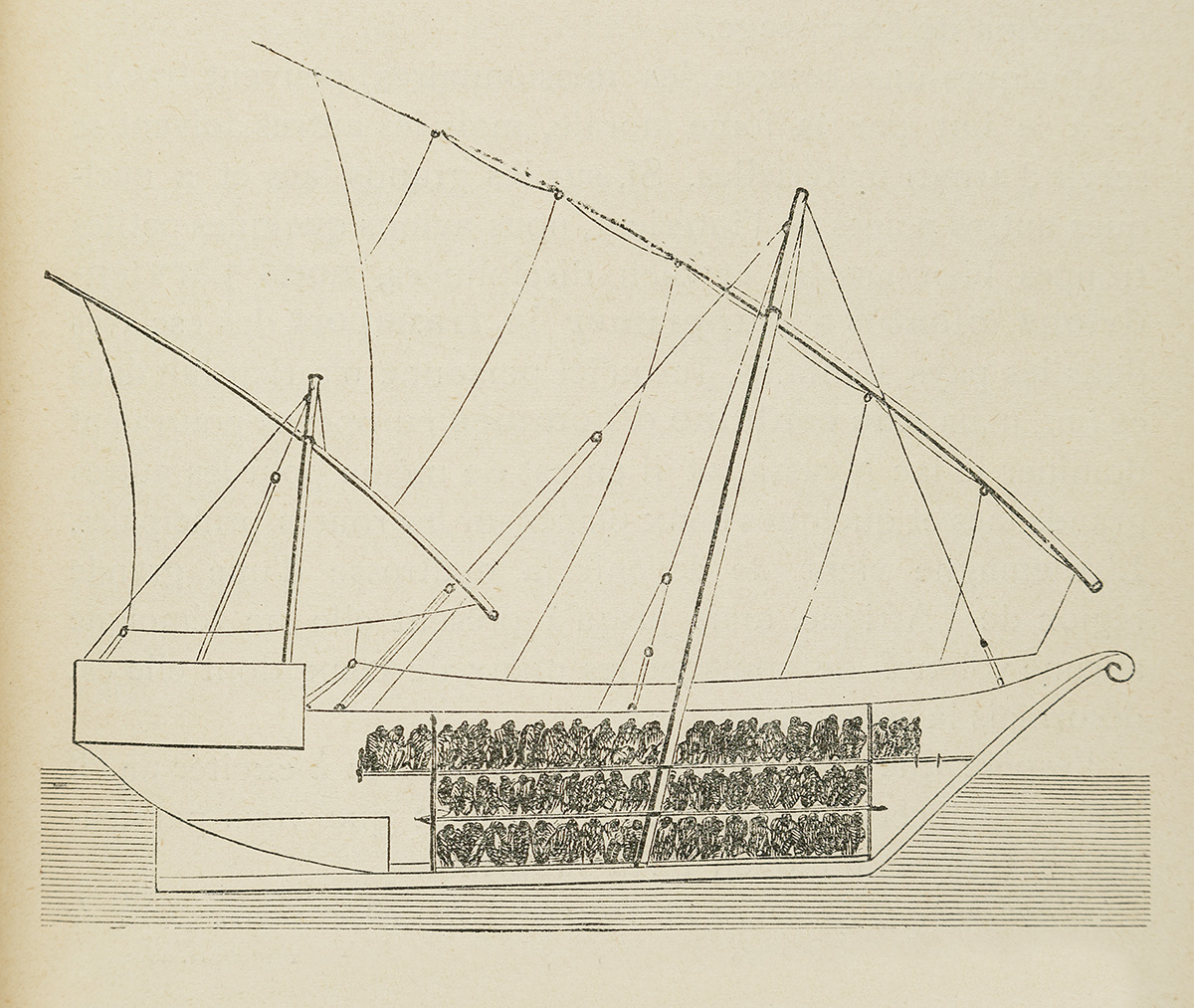

The Atlantic and the Indian Ocean slave trades were two distinct phenomena. First of all, for the latter, the trade goes back to Antiquity. Also, for the second half of the 19th century, the trade in slaves was not an exclusive activity, meaning that the vessels were not specifically equipped for the slave trade, as was the case for the Atlantic. This is one of the reasons why, once the British and French navies were committed to abolishing the trade, they found it so difficult. It was, indeed, very often far from easy to identify persons involved in the slave trade. Very few vessels transported large numbers of slaves. An average of 25 could be counted on board the dhows sailing along the coasts of East Africa in the 1860s and 1870s. In this respect, the case of the ship the Djamila is somewhat of an exception. It was difficult to differentiate between the slaves and the other members of the crew, since, in general, the slaves were not chained up in the hull of the ship, contrary to the images that were presented in Europe during that period. If such cases existed, these were exceptional.

In addition, during the first half of the 19th century, while the trade in the western Indian Ocean was dominated by European, in fact mainly French vessels and sailors, during the second half of the century we can note a preponderance of dhows sailing with Swahili crews and having their ship-owners in Zanzibar, Oman, Arabia, the Persian Gulf and the west of India. Very often, these traders sailed with no flag flying and no official documents on board, thus further complicating the task of the abolitionists of the period, as well as that of today’s historians.

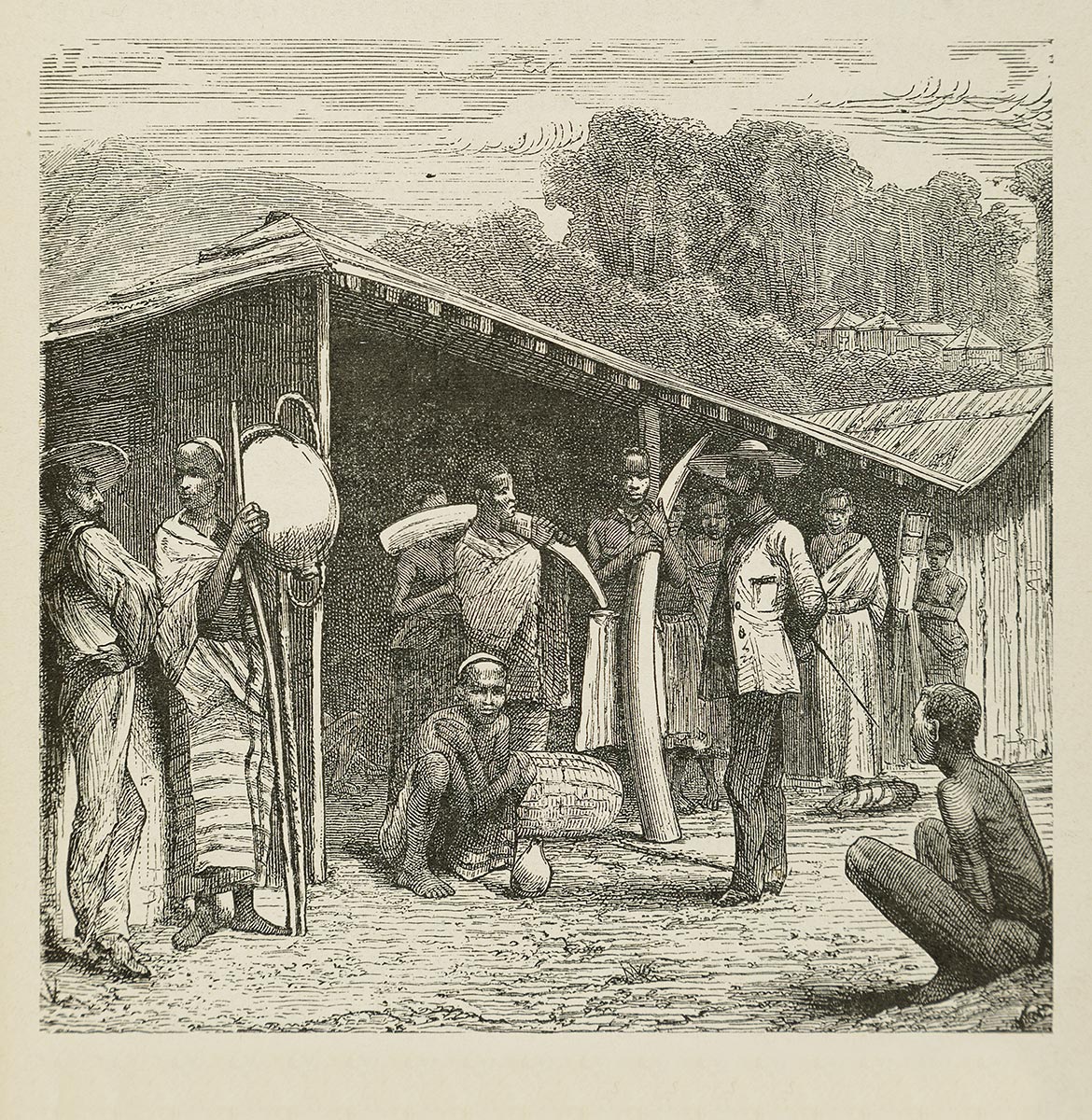

During the period of expansion of the European empires, dhows – sailing ships with long hulls and equipped with one or two triangular sails – symbolised, in the Western imagination, the trade of African slaves in the Indian Ocean. The word dhow, ‘boutre’ in French, is, however, a term referring to over 80 different types of sailing ship, not necessarily linked to the slave trade. However, as from the 1870s, the European press presented these vessels as being the incarnation of “the last slave‑trade” to be eliminated. Through these vessels were stigmatised ‘Arabs’, ‘Muslims’ or the Islam religion, even though this global trade, as well as the trans-Atlantic activity, was far from limited to a single religion or group. This is what is represented by the engraving published in the Illustrated London News in 1889, depicting ‘Arab’ slave traders.

It was too easily forgotten that the slave trade had been dominated by Europeans during the first part of the century, and that during the later part of the century, many of the ‘slave trading’ dhows that sailed would be flying European flags and manned by Swahili crews and captains from all corners of the Indian Ocean.

While not exclusive, the slave trade in the western Indian Ocean went hand-in-hand with transport of goods representing the trade in general within this maritime space, consisting, notably, of spices, coffee, ivory, pearls, dates, copal, dried fish and weapons. Combined with trading of human beings, these goods would be transported, for example on board dhows sailing between the east coast of Africa (Lamu, Mombasa, Zanzibar or Kilwa), along the Red Sea (Aden, Mukulla and Mocha), the Gulf of Oman (Mascat and Sour), the Persian Gulf (Bandar Abbas, Bushire and Basra), as well as the west coast of India (Diu, Surat, Bombay, Calicut and Cochin).

Trading in human beings in the Indian Ocean was mainly aimed at providing a servile workforce for the clove and coconut plantations developed along the east coast of Africa by the Sultanate of Zanzibar as from the 1840s. It also developed in response to the need for labourers working on date plantations and irrigation works on the Arabian peninsula, as well as fleets involved in fishing for pearls in the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea. In Madagascar, slaves were used to develop agriculture and industry. In addition, the slave trade provided persons for the domestic slave market, to be used by the wealthy classes over the entire region, as well as caravans of porters used to transport ivory towards the coast.

As regards France, despite the abolition of the slave trade in 1817, then slavery itself in 1848, the illegal trade continued to provide slaves, and ‘indentured labourers’ for the French colonial plantations in the Indian Ocean, as reflected in the case of the Djamila. The trade gave rise to a new form of commerce between East Africa, the Comoros, Madagascar and Reunion. During second half of the 19th century, approximately 50,000 ‘indentured labourers’ were thus ‘recruited’ by estate owners on these islands. .

While the European powers, at the time fully expanding their colonies, attempted to abolish the slave-trade during its peak, it only truly declined very late on. Abolition and colonisation only resulted in a significant decrease, without totally eliminating the activity. Historians have shown that the trade only came to a complete stop after World War I, when the trade in dates and pearls from Arabia declined through globalisation. We can note that the activity continued in a residual manner at least until the 1950s. Indeed, the British admiral Lord West, evoking his first years of service in the western Indian Ocean during this period, recorded arraignment of a vessel transporting slaves off the coast of Oman. The slaves were young women from Zanzibar, captured to be sold somewhere in the Persian Gulf, where slavery was not abolished until late on: notably in Qatar in 1952 and in Oman in 1970.