Reunion Island and South Africa share a common history of slavery. In order to share this history, the Departmental Council of Reunion has signed a partnership agreement with Iziko Museums of South Africa. This initiative is part of the project to create the Museum of the estate and of slavery in Reunion. The agreement will result in an exchange of exhibitions between the Villèle Museum and the Slave Lodge Museum, two heritage institutions working on the same theme, centred on the history of slavery.

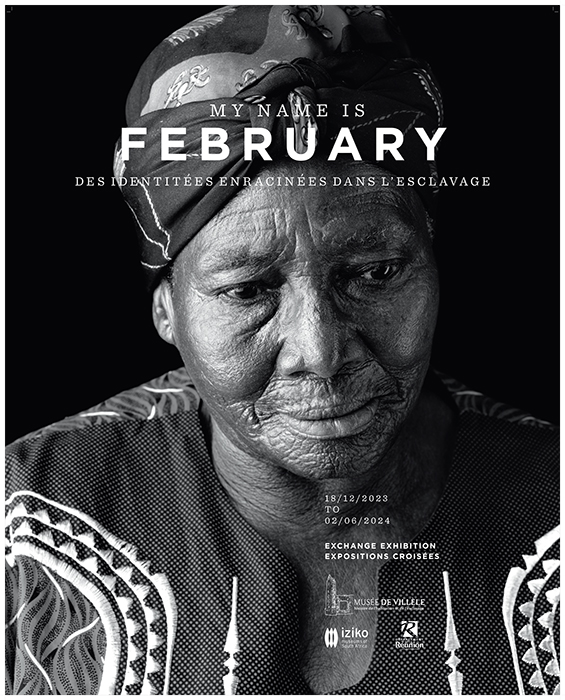

As 2023 draws to a close, visitors can look forward to a series of cross-disciplinary exhibitions. While Africans have been discovering The Name of Freedom, an exhibition from the Reunion departmental Archives, since 1st December, visitors to Villèle museum will be able to see My Name is February from 19th December.

Enslaved people were brought to the Cape by the Dutch East India Company as forced labour for the expanding settlement at the Cape. The first ship-load of slaves was brought in 1658. Between 1658 and the early 1800s over 63 000 men, women and children were snatched from their homes in places such as Madagascar, Mozambique, Zanzibar, India and the islands of the East Indies such as Sumatra, Java, the Celebes, Ternate and Timor (Indonésie) and brought to the Cape as slaves.

Stripped of their homes, families and friends, cultures, languages, religions, and identities these enslaved people became the property of others. They had no rights to their own children; their production and reproduction was controlled; they could not own property; and did not have the freedom to choose who they wanted to work for or the kind of work they wanted to do.

Initially the Dutch East India Company was the biggest single slave-holder at the Cape. As more and more free burghers occupied land at the Cape they too made use of slave labour and by the early 1700s there were more enslaved people ‘owned’ by the free burghers.

While the so-called “company slaves” generally kept their names, though incorrectly spelt by the officials, with the area that they were from appended to the name (e.g. Abasembie van Zanzibar, Nelanga van Mosambique, Mabiera from Madagascar, Toemat van Sambouwa, Domingo van Malabar, etc.) the slaves ‘owned’ by the free burghers were generally given new names. The renaming of slaves was one way of stripping them of their identity.

In some cases the free burghers gave slaves classical names, often based on an emperor or some mythical figure — Alexander, Hector, Titus, Hannibal. Slaves were also given Old Testament names like Adam, Moses, Abraham and David. Others still, were given comical and insulting names such as Dikbeen and Patat.

Many of the slave-holders resorted to giving slaves calendar names based on the month in which they were brought to the Cape, such as February, April and September.

This exhibition, based on interviews with people whose surnames derive from calendar names, opens up dialogue about the way in which the often forgotten and neglected slave past has shaped our heritage not only at the Cape but in South Africa as a whole. In taking up this narrative we wish to pay tribute to the thousands of people forcibly uprooted from their homes in various parts of Africa and Asia, who were brought to the Cape and whose labour contributed to the building of South Africa’s cities, towns and farms.

“If you choose to lie down, then you stay down. But it’s your choice to get up — and these are the stories of those who have. These are stories of hope.” Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu